Shambhavi Roy

Shambhavi Roy

‘

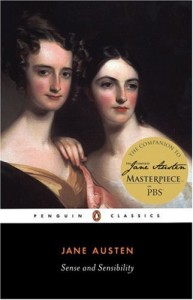

Fiction writers often struggle with various questions related to subplots: How should I structure my subplots? How much space should my subplots consume? What kind of relationship should the subplot bear to the main plot? Should the subplot be congruent or opposed to the main plot? Let’s consider the novels Sense and Sensibility by Jane Austen and The Accidental Tourist by Anne Tyler as an entry point into the study of subplots in general and the related techniques of character grouping and gradation.

Aristotle taught that the best plots proceed through a series of reversals and recognitions. John Dufresne is his book The Lie That Tells a Truth tells us that episodes do not necessarily make a plot. He says, “Plot is the writer’s arrangement of events to achieve a desired effect. It is the magnet to which all other narrative elements attach.”

Plot is something, I believe, that can be coaxed into being. John Dufresne says that “a plot begins to form as soon as you ask yourself the appropriate questions: what does my central character want? What is preventing her from getting it? What does she do about the various obstacles in her way? What is the outcome of what she does? What climax does this all lead to? Does she get what she wants in the end? Plot, then, is the element of fiction that shapes the other elements—character, theme, point of view, language, and so on—into a story.”

Now let’s turn our attention to subplots, the main topic of this essay. In The Enamoured Knight, Douglas Glover says this about subplots: “In its simplest and most direct form the subplot is another plot, involving another set of characters, weaving through the novel.” Subplots can vary in size but every novel must have at least one to achieve the resonating or echoing effect that a novelist tries to achieve by modulating or reduplicating situations and characters, by having several people falling in love or dying or praying in different ways—dissimilar people solving the same problem or similar people confronted with dissimilar problems.

In his essay “Emotion of Multitude,” W. B. Yeats says that “the Shakespearean drama gets the emotion of multitude out of the subplot which copies the main plot, much as a shadow upon the wall copies one’s body in the firelight. We think of King Lear less as the history of one man and his sorrows than as the history of one man and a whole evil time. Lear’s shadow is in Gloucester, who also has ungrateful children, and the mind goes on imagining other shadows, shadow beyond shadow, till it has pictured the world. In nearly all of Shakespeare’s plays the subplot is the main plot working itself out in more ordinary men and women, and so doubly calling up before us the image of multitude.” Yeats seems to imply that if we read the experiences of one man, we may imagine it rooted in his own unique personality or providential in nature or the result of unprecedented or uncommon play of events. But if we notice similar dramas unraveling in several individuals’ lives we may be forced to look beyond the characters and we may end up understanding the thematic issues the authors wants to highlight.

Usually, subplots have graded characters closely related to the main characters. On the topic of graded characters, Glover offers us this: “Graded characters are characters in narrative who share, in a more or less exaggerated or more or less attenuated fashion, thematically crucial experiences in such a way as to create structural parallels” (The Enamoured Knight). A group of friends or schoolmates or army buddies make good subplot characters. “The advantage of the near relations between characters on plot and subplot lines is that they can interact with and observe one another naturally” (The Enamoured Knight). However, we must keep in mind that the different character groups we see in novels often—class, family, working groups—are options we see frequently, but they are not the only possibilities for running subplots.

All right, now let’s turn to Sense and Sensibility to better comprehend what might have led Jane Austen to make use of a plot-subplot structure with graded characters. In this novel, after Henry Dashwood dies, his three daughters and his wife inherit a small and insufficient sum, so the Dashwood girls must marry to find respectability and secure their futures. Although their stepbrother, John Dashwood, promised his dying father he’d take care of his stepmother and sisters, he decides to offer them nothing under the influence of his greedy wife, Fanny. Then, a pleasant unassuming man, Edward Ferrars, Fanny’s brother, visits Norland and Elinor, the prudent Dashwood girl, gets attached to him. Fanny disapproves of the match and complains to Mrs Dashwood, Elinor’s mother, which results in the hasty departure of Elinor, her sisters and mother from Norland to a small rental cottage they’ve found for themselves in Devonshire. Marianne, the younger sister, full of fine sensibilities—which is a euphemism indicating her excessively emotional and impetuous temperament—disregards Brandon, an older, mellow, reserved man and finds her soul mate in a dashing young man named Willoughby, who, not surprisingly, resembles Marianne. Demonstrative and passionate, Willoughby and Marianne never leave each other’s side, leading to much public speculation about their relationship. Then, all of a sudden, Willoughby leaves. Marianne, a romantic, suffers a “violent oppression of spirits” while waiting for him to return. Soon she learns of Willoughby’s engagement with someone else for monetary reasons and falls sick and nearly loses her life as a result of the heartbreak. Like Marianne, even Brandon is wronged by Willoughby: Willoughby flirted with and impregnated a girl-child, Eliza, under Brandon’s guardianship. Even Elinor faces ill-luck in love—Edward is secretly engaged to Lucy, a girl who suffers from a want of delicacy and integrity of mind. But Elinor does not share the news of Edward’s engagement with her family for a long time and bears hardship with a sense of forbearance. In the end, Elinor turns out to be the fortunate one, although just by chance: Edward’s fiancé, Lucy, breaks her engagement with Edward so he can unite with Elinor; however Marianne must content herself to be with Brandon, although she didn’t care for him before.

Sense and Sensibility, published in 1811, anonymously, brought its writer no fame during her lifetime, although it was an instant success. With a recent surge of interest in Jane Austen, the novel is more widely read and proclaimed today than it ever was. Written in third person from the point of view of an omniscient narrator, the novel explores the problem of finding a life partner and whether sense or sensibility leads to a better match.

In this novel the plot and the subplot occupy nearly equal space and are accorded equal consideration, forming parallel plot-subplot structure. Right in the beginning, on page three, Jane Austen sets the stage for parallel plots with graded characters.

Elinor, this eldest daughter whose advice was so effectual, possessed a strength of understanding, and coolness of judgment, which qualified her, though only nineteen, to be the counselor of her mother, and enabled her frequently to counteract, to the advantage of them all, that eagerness of mind in Mrs. Dashwood which must generally have led to imprudence. She had an excellent heart; her disposition was affectionate, and her feelings were strong; but she knew how to govern them: it was a knowledge which her mother had yet to learn, and which one of her sisters had resolved never to learn. (3)

Note the way Elinor’s character is described in relation to that of her mother and her sister. In the next paragraph, the author offers us this about the younger sister, Marianne.

Marianne’s abilities were, in many respects, quite equal to Elinor’s. She was sensible and clever; but eager in everything; her sorrows, her joys could have no moderation. She was generous, amiable, interesting: she was everything but prudent. The resemblance between her and her mother was strikingly great. (3)

Throughout the novel, the author uses the words “prudence” in reference to Elinor and “eagerness” and “imprudence” in reference to Marianne and her mother, Mrs Dashwood. Elinor and Marianne—sisters, young, unmarried, constrained by their financial situation, the fact they are women, and the fact they must marry to secure a future for themselves—belong to the same character group, even though they are temperamentally apart. They are both well brought-up girls, who enjoy books and are fond of arts, although Marianne’s fondness for arts is more vehement in nature. Elinor draws and Marianne plays piano. They love their mother and each other. But to illuminate the theme of the novel the author must draw out the differences in the outlook of the two Dashwood girls. So to accentuate their heterogeneity, the sisters form pairs with men who reflect their personalities. Like Elinor, Edward has a quietness of manner and is amiable, warm and affectionate. Willoughby is frank and vivacious and as passionate about music and dancing as Marianne. Not just Elinor but even Edward and Brandon represent sense and the pair, Marianne and Willoughby, sensibility and indiscreetness. Edward and Willoughby mirror the dispositions of the women they are with, though not entirely. Elinor is not as shy as Edward, and Edward doesn’t have the same interest in arts as Elinor. The narrator tells us this about Willoughby and Marianne: “The same books, the same passages were idolized by each—or if any objection arose, it lasted no longer than till the force of her arguments and the brightness of her eyes could be displayed.” Jane Austen takes time to define the spectrum of her characters’ beliefs and their propensities, and then these graded characters will trudge along parallel plot lines to explore the central theme of the novel: when looking for a life partner, is it better to follow reason or sensibility? Whether sense or sensibility is the winner in the end?

Both sisters fall in love; they are presented with obstacles and find resolutions. The novel unfolds in a pattern. We see some event bear down upon one of the sisters and observe her reaction to the life event and then we see a similar occurrence in the other sister’s life and witness her response and learn what others think of the whole business. “In fiction,” E. K. Brown tells us, “the rhythmic arrangements that move us most are those where repetition is enveloped in variations, but never so enveloped that it appears subordinate.” That is exactly what Jane Austen seems to want to accomplish. Although the arcs of the two parallel plots cover the same points and are a bit repetitive on the surface, they are designed to achieve the opposite effect: highlight differences and illuminate the theme.

Compare Elinor’s gentle anguish, when she discovers Edward is engaged to Lucy, to Marianne’s finding Willoughby with a woman at a party.

Elinor for a few moments remained silent. Her astonishment at what she heard was at first too great for words; but at length forcing herself to speak, and to speak cautiously, she said with a calmness of manner, which tolerably well concealed her surprise and solicitude—‘May I ask if your engagement is of long standing?’ (87)

Here’s Marianne’s comportment in a somewhat similar predicament.

Marianne, now looking dreadfully white, and unable to stand, sunk into her chair, and Elinor, expecting every moment to see her faint, tried to screen her from the observation of others, while reviving her with lavender water.

‘Go to him, Elinor,’ she cried, as soon as she could speak, ‘and force him to come to me. Tell him I must see him again—must speak to him instantly.—I cannot rest—I shall not have a moment’s peace till this is explained—some dreadful misapprehension or other.—Oh go to him this moment.’ (119)

When the sisters are about to leave their childhood home in Norland, Marianne sheds tears, but Elinor finds the decision to move prudent and refuses to dissuade her mother, even though her love-interest is in Norland.

A romantic, Marianne says, “What have wealth or grandeur to do with happiness?” “Grandeur has but little,” says Elinor, “but wealth has much to do with it.” Elinor falls for Edward who is not handsome, and his manners require intimacy to make them pleasing. Marianne, who doesn’t approve of her sister’s beau entirely because Edward has no spirit and is not striking enough, falls in love with Willoughby, a charming personality in everyone’s opinion. Even Mrs. Dashwood commends Marianne’s choice and finds Willoughby faultless, although Elinor can clearly see a problematic propensity, in which Willoughby strongly resembles Marianne, of saying too much what he thought on every occasion, without attention to person or circumstances.

I counted seventeen different occasions when Jane Austen brings out the striking diversity in the conduct of these two sisters. The sisters form two parallel mountain ranges reflecting sound off each other so the echo reverberates in the reader’s mind. The author seems to pitch antithetical ideas because, I believe, human beings do not understand in a vacuum but in relation to one another. In E. K. Brown’s terms, the two sisters “irradiate each other and become clearer by irradiation.” By offering contrasts and similarities the author is according greater depth to these characters and the social milieu, while trying to get at the hidden truth.

In the end, Elinor, although prudent, selfless, calm, hardly fairs better than Marianne, even though Marianne is eager and imprudent. Elinor’s cautiousness is not entirely a helpful trait, given that she cannot discuss her feelings openly and is unsure how Edward feels for her. Ultimately, she unites with Edward only because of happenstance. So, in a way, the author declares “sense” as the winner somewhat grudgingly. We see the same pattern reappear in the cast of characters supporting the two parallel plots: Willoughby, Brandon, and Edward Ferrars. Shy and sensible, Edward loves Elinor but gets engaged to Lucy because of a past commitment. If Lucy didn’t abandon him, he could count on a miserable life ahead of him. Brandon, another calm, rational, caring man, never marries his first love, fails to protect the child, Eliza, under his guardianship, and finally unites with Marianne only after Willoughby deserts Marianne. True, Willoughby finds himself in a frightful place toward the end of the novel, but then, he has abandoned sense and even sensibility for that matter—he has lived a life of extreme indiscretion: rejected Marianne, flirted with and impregnated a young girl, and married solely for monetary reasons. The author has placed Willoughby near the edge of the spectrum of her characters, but with the help of her other characters, she argues for and against her ideas imparting depth to the discourse.

It is clear that the main benefit of having closely related characters and a tightly interwoven plot-subplot structure is to act as the glue holding and unifying the story and bestowing a direction and a sense of purpose. The author shows several characters struggling to find life partners so we get a flavor of the emotion of multitudes. The plots and the subplots point in the same direction so the theme is emphasized and we get a sense of the larger world. How else would we recognize the complexities inherent in identifying a life partner, and the fact that it is so hard for anyone to be right in this matter?

So what other benefits Jane Austen reaps by having parallel plots with graded characters. As I read Sense and Sensibility and considered the topic of graded characters, I also realized that having two sisters driving parallel plots was also serving as a subtle memory rehearsal device by reinforcing and comparing constantly. When Elinor expresses her thoughts on the subject of move from Norland and then Marianne wails over the same issue, the reader knows for sure the family is moving. Let’s take a moment to appreciate the role this repetition plays. The more a bit of information or an idea is repeated or used, the more likely it is to eventually end up in long-term memory, to be “retained.” People tend to more easily store material on subjects that they already know something about, since the information has more meaning to them and can be mentally connected to related information. So if you want your readers to retain bits from your novel in their long term memories you may want to consider closely related characters and an interlaced plot-subplot structure so these characters can frequently cross each other’s paths and reflect on each other.

In the end, we must recognize that narrating Marianne’s story, along with Elinor’s, doubles the length and makes the novel more interesting. Far more engrossing, Marianne and Willoughby serve as a balance against Elinor and Edward, who are shy, reserved and not so amusing. Does that mean if a protagonist is ill-tempered or morose, we should consider a lively and more engaging character driving a subplot to relieve the strain off a difficult topic? Definitely something we should keep in mind.

Now let’s turn to The Accidental Tourist to see the plot-subplot structure in that novel. After Macon Leary’s twelve-year-old son gets shot and killed, Macon and his wife Sarah separate, because Sarah cannot find any comfort in her husband.

Left alone with just an unruly dog for company, Macon has difficulty sleeping and wishes his wife would return. Then he breaks his leg and is forced to move to his sister Rose’s house where Rose and Macon’s two brothers, Charles and Porter, live. To help train his dog, whose violent tendencies have increased as a result of the move, Macon hires Muriel Pritchett. She is a divorced woman and the mother of a seven-year-old reclusive boy with medical problems from the time of his premature birth. At first Macon refuses to get involved with Muriel, but, ultimately, her eccentricities and her problems draw him out of his shell. He cohabits with her in her house, which is in a slummy neighborhood, and teaches her son math and plumbing techniques, even though he is not in love with her or even entirely comfortable with her, for that matter. Disorganized, unsettling and unpredictable, Muriel has a “nasty temper, a shrewish tongue and a tendency to fall into spells of self-disgust.” Not surprisingly, Macon’s siblings disapprove of the relationship and try to convince him she is not the right woman by reminding him she is much younger and just out there to catch a man so he could provide for her. At this point, Macon’s ex-wife, aware of Macon’s live-in relationship, tries to woo him back. As Macon has never really gotten over Sarah, he cannot help but move back with Sarah; but Muriel, unwilling to give up on Macon, follows him around when he goes on a business trip to Paris. Finally, after an argument with Sarah, Macon realizes that he and Sarah “have used each other up.” He realizes he must embrace his new life with Muriel and leave the memories of his dead son and his ex-wife behind.

Anne Tyler’s tenth novel, written in 1985, The Accidental Tourist was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize and won the National Book Critics Circle Award for Fiction. With a clear plot-subplot structure, the main story has Macon Leary as its lead character, and the subplot features his sister Rose. The minor subplots are about Macon’s two older brothers, Porter and Charles.

Just as in Sense and Sensibility, the subplots in The Accidental Tourist are driven by close relatives, the sister and brothers of the protagonist. As if the fact that Rose and Macon are siblings isn’t enough to bring them together often, Rose has a relationship with Macon’s boss, Julian, and this gives the author an opportunity to talk about Rose every time Macon meets Julian. Even Macon’s estranged wife, Sarah, is close to Rose and when Macon and Sarah reconcile they discuss Rose’s situation in life. The relationships form a tightly woven pattern so the characters can observe each other and compare and contrast.

Just as the two sisters in Sense and Sensibility are both similar and different, Macon and his sister and his two brothers resemble each other and have traits that establish their distinctness as human beings. All of the Leary children are grammar fanatics, orderly, somewhat socially stunted, and idiosyncratic. They even look alike: “Their hair had an ashy cast and their eyes were a steely gray. They all had that distinct center groove from nose to upper lip. And never in a million years would Alicia [their mother] have worn an expression so guarded and suspicious.”

Rose has her kitchen so alphabetized that she keeps allspice next to ant poison and considers it perfectly normal to live with her brothers. Macon sleeps in a body bag, does not use a dishwasher, and stalks around in circles while showering, sloshing the day’s dirty clothes underfoot. Even though the details differ, the siblings have the same strange quirky feel about them, as if they are different shades of each other. But the siblings wouldn’t become real in our eyes if the author didn’t list their unique characteristics to round them up as human beings.

So Anne Tyler lets us know that Rose is the only social Leary, who helps out neighbors and old relatives; Porter is the best looking Leary kid, talkative, and able to run finances and plan taxes; Charles, a sweet-faced man who never seems to move; and Macon, even though he shares several character traits with his siblings, is not always comfortable with the idea of abiding with Rose and his brothers. He experiences moments of anxiety when he wonders if has gone any further in life since his childhood days. And he is also the only one who considers the fact that that they might be unconventional. When Julian visits Rose’s home, Macon tells Rose that Julian was there just because “he hopes we’ll do something eccentric.” Macon wishes none of his siblings would say or do anything awkward around Julian.

Unlike her three brothers, Rose wants to experience love. Rose says, “Love is what it’s all about. On soap operas everything revolves around love.” But Charles and Porter, after their failed marriages, seem content in Rose’s house with Rose overseeing the housekeeping for them. Even Macon does not seek romantic associations actively, although he can get entangled into them. To a certain extent, Macon and Rose share the desire to be in romantic relationships, and therefore, their lives evolve in a similar fashion, creating a congruent plot-subplot structure. After Rose marries Julian and lives with him for a while, she begins to get disoriented with the newness of her life and moves back with her brothers. Similarly, Macon abides with Muriel for some time and then moves back with his estranged wife. In the end, both Macon and Rose unite with their lovers, although in variant ways—Macon leaves his estranged wife and goes back to Muriel and Julian begins to live with Rose and her brothers. .

Now let’s focus for a minute on the textual space devoted to Macon versus that devoted to Rose. As this novel has a clear plot-subplot structure, Macon enjoys the lion’s share of space. Rose does not appear in the first chapter—there is not even a mention of her. She appears for the first time in the second chapter and then disappears till the end of the fourth. The fifth chapter is dedicated to describing Macon’s siblings, particularly Rose. And from then on, Rose is mentioned in every chapter, even if it is just to let us know that she drove Macon to Julian’s place. In the last chapter, although we don’t get to see Rose, Macon’s ex-wife, Sarah, informs Macon that Julian has moved in with Rose and the brothers. Of the twenty chapters in this book, Rose occupies significant space in just four and the brothers are given much less consideration.

So why have Rose and the brothers? What purpose do they serve? Several, in my opinion. First, with the help of these subplots, the author highlights the theme of the novel—the nature of love and the fact that for successful love relationships one has to reach a point of wisdom or a compromise between the desire for order and chaos. As we see Macon and Rose struggling to understand what they want and where they belong, we get the “emotion of multitudes,” a feeling that even though we are reading a novel with a simple structure and few characters we are in a large and teeming world where everyone is trying to fathom the meaning of love, marriage, and compromise in an ever changing world.

Note how all the Leary kids seem to drift back to their place of origin. After Macon breaks his legs, he moves in with Rose and his brothers and experiences quiet contentment. Macon gets involved with Muriel only because his dog, Edward, is unsettled in unfamiliar surroundings and begins to attack everyone. Even though Macon misses some aspects of his life at Rose’s place, he is lulled by the ease and simplicity of his childhood routines and hardly seems to desire new relationships. Even though he says his lack of interest in sex is a result of his son Ethan’s death, one cannot help notice that he has always shunned newness and unfamiliarity. Even when he was young, it was Sarah who initiated and drove the relationship forward, not Macon. Anne Tyler sheds light on the same appeal for one’s native environment through Rose. Rose, fascinated by the concept of love because she’s never been in a relationship before, falls for Julian and marries hastily, but within a few days of her wedding, she leaves her marital home and comes back to live with her brothers. She unites with Julian only because he sheds his traditional idea of a marital home and moves in with her brothers. Julian says, “She’d worn herself a groove or something in that house of hers, and she couldn’t help swerving back into it.” Even Charles and Porter have the same regard for familiarity as Macon and Rose. And all the Leary children love and deeply care for each other. Rose ministered to the needs of her ailing grandfather and cooks and cleans for her brothers, and they, in turn, care for her in a subtle, heartwarming way. Looking at Macon, Rose, Porter and Charles, readers may begin to wonder if, at some level, we all have the same affinity and weakness for our first homes. We do not know if this is the effect Anne Tyler wanted to achieve but nevertheless with the help of her subplots and graded characters, she underscores the human tendency to value familiarity—the sense of well-being we associate with our childhood home—and the intimacy we share with our siblings and other blood relations.

What other purpose do the subplots serve? What other “emotion of multitudes” does the author hope to evince? Let’s consider the partners the Leary kids are attracted to. Rose, a sober, prim woman, who “folds her hair unobtrusively at the fact of her neck where it wouldn’t be a bother” and wears “spinsterly and concealing” clothes, finds love in Julian, a playboy, living in a Singles apartment. Rose’s brothers try their best to dissuade her from getting involved with Julian but for some reason she cannot resist. Even Porter and Charles were married to women unlike them, who made fun of them. Macon, a man in his forties, obsessively organized, grammar fanatic, has a strange attraction for Muriel, a talkative, neurotic, disorganized woman. Every one of Macon’s siblings thinks Macon and Muriel are unsuitable for each other. But when Macon moves back with his ex-wife, he misses Muriel’s eccentricities and her misusages. Even though Macon and his sister and brothers have a fondness for the familiar, they are also enthralled by the unfamiliar, and the same can be said about their spouses. We, the readers of The Accidental Tourist, wonder if most of us “in a more or less exaggerated or more or less attenuated fashion” exist in a confused state, drawn toward and repelled by the familiar.

Now let’s turn our attention to the two married couples in The Accidental Tourist. Even though Macon and Sarah have been together for decades, even though he loves her dearly, the only comfort they seem to accord each other is the comfort of routine. When Muriel tells Macon she wants to marry him, he says, “I don’t think marriage ought to be as common as it is; I really believe it ought to be the exception to the rule; oh, perfect couples could marry, maybe, but who’s a perfect couple?” And then later, thinking about a conversation Macon had with his wife, we learn this: “Thinking back on that conversation now, he [Macon] began to believe that people could, in fact, be used up—could use each other up, could be of no further help to each other and maybe even do harm to each other.”

On the other hand, Macon enjoys the cozy, sloppy presence of Muriel, a woman he does not love. At times he is ashamed of Muriel but still ends up making a home with her. And Rose loses her fascination for marriage soon after she gets married and returns to her childhood home. Although she is attracted to Julian, a traditional wedding and a married life provide no comfort to her. Ultimately, her marriage survives because Julian moves back with her forming an unconventional arrangement. So is there some truth that the author wants to shed light on here? Is it possible to live and find comfort in unorthodox relationships and arrangements outside of marriage with people we do not even love? Is marriage as an institution worthy of the respect we accord to it, given that people and their conditions change so frequently?

After studying these two novels, Sense and Sensibility and The Accidental Tourist, it is clear that their subplot structures are different in key ways. Rose occupies far less space than Marianne, probably because Jane Austen wants to initiate a dialogue with her readers, but Anne Tyler seems to open our minds to a new idea, one that may not have too many takers in the middle class. The key thing to note is the fact that subplots must parallel or reflect the main plot, otherwise the various elements of a novel fly apart and the text lacks rhythm and unity of thought.

—Shambhavi Roy

.

Shambhavi Roy, a graduate of Vermont College of Fine Arts, lives in Saratoga, CA, with her husband and two kids.

Wonderful essay, Shambhavi. Congrats!