The author outside a bakery in Bamberg, Germany

The author outside a bakery in Bamberg, Germany

/

For a long time, as I read, I paid no more attention to the length of sentences than I did to their grammar or syntax. It wasn’t until I discovered Marcel Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu that I learned to appreciate how long and short sentences can be juxtaposed for emphasis and how syntax can mimic the flow of thought and action. Of course, Proust is famous for his long sentences, some of which extend well beyond 200 words; these sentences intrigued me the most. The closest analogy I can imagine is that discovering Proust’s long sentences was like discovering a new genre of music, as if I had lived my life without knowing there existed such things as symphonies. If prose is like music, then some types of writing must resonate with particular people just as we have different musical tastes, and Proust’s swirling syntax certainly resonated with me. Eyes opened, I pursued the subject and discovered the rich variety of ways other writers employ long sentences to dramatize the actions and thoughts of characters.

But why labor to construct a 200-word-long sentence when a dozen shorter sentences can communicate the same information and not task the reader’s attention and patience? A sentence is greater than the sum of its propositions. A sentence’s syntax – the order in which the words of the sentence are arranged – affects its emotional impact, e.g. placing a proposition at the end of a sentence engenders suspense. But the possibilities extend far beyond this simple example. In Artful Sentences Virginia Tufte limns an incredible range of syntactic arrangements that function symbolically. She describes “syntactic symbolism” as when “syntax as style has moved beyond the arbitrary, the sufficient, and is made so appropriate to content that, sharing the very qualities of the content, it is carried to that point where it seems not only right but inevitable” (271). In the following excerpt from the novel Correction, Thomas Bernhard uses repetitive syntax to symbolically represent the protagonist’s mania for perfection, viz. he corrects himself while explaining the process of correction:

We’re constantly correcting, and correcting ourselves, most rigorously, because we recognize at every moment that we did it all wrong (wrote it, thought it, made it all wrong), acted all wrong, how we acted all wrong, that everything to this point in time is a falsification, so we correct this falsification, and then we again correct the correction of this falsification . . . (242)

Tufte cites many examples to illustrate the diversity of emotional and mimetic effects of syntactic symbolism. What Tufte calls syntactic symbolism, David Jauss calls “rhythmic mimesis” and notes that “sometimes the syntax does more than convey the appropriate emotion; sometimes it also rhythmically imitates the very experience it is describing . . .” (70-71).[1] The rhythm of the syntax in Bernhard’s prose conveys the protagonist’s exasperation while simultaneously informs on his character. But the “experience” Jauss refers to can mean movement, whether physical action or the more nebulous movement of human thought. I’ve found these types of motion mimesis to be particularly effective applications of the extended syntax of long sentences.

It is important to note that neither Tufte nor Jauss restrict their examples to long sentences; rhythmic mimesis can be conveyed by sentences of all lengths. But given my penchant for longer sentences, I began looking for how they might be used in the manner Jauss and Tufte describe. After surveying a wide range of fiction (different time periods, genres, narrative modes, etc.), I noticed a pattern whereby authors applied long sentences effectively to create a rhythmic mimesis of motion, speech, consciousness, and even character. In the last category a long list can be used to communicate a fictional character’s character, as exemplified by Nicholson Baker’s obsessive memoirist in The Mezzanine. Motion mimesis – using prose to imitate actions – is an excellent use of long sentences with stunning examples found in such diverse works as The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, many of Faulkner’s stories, and the fiction of David Foster Wallace. Spoken language is no less rhythmic than written, and the Czech writer Bohumil Hrabal demonstrates that long sentences can be used to capture the personality and style of a teller of tall tales in his 1964 Dancing Lessons for the Advanced in Age. In the depiction of the conscious mind in fiction, James Joyce’s achievement in Ulysses still exemplifies how the syntax of long sentences can mimic the rhythm of thought. Two contemporary writers who answered the challenge of capturing the mind’s stream of consciousness include: David Foster Wallace, who in Infinite Jest takes the reader into the realm of the subliminal, of dreams and drug-induced states; and the French writer Mathias Énard, who pushes the boundaries of what we call a sentence even further than Joyce, with his book-length sentence in his 2008 novel Zone.

/

The List

The most obvious reason to add propositional content to a sentence is to increase the amount of descriptive detail, and long sentence constructions often contain lists. But the point isn’t to string together a random catalogue of items just to fill the page: lists can elucidate character.

Nicholson Baker’s novel The Mezzanine is a daydream, a meditation on life, on questions large and small. The story, presented as a memoir, is told in first-person point of view by Howie, a thirty-year-old factotum obsessed by his childhood. The novel is short, 135 pages, composed of fifteen chapters, many of which have long, detailed footnotes wherein the narrator indulges his love for digression. Howie’s conflict is with himself. He wants to achieve what he calls a “majority,” that is, a moment when he will have “amassed enough miscellaneous new mature thoughts to outweigh and outvote all of those childish ones” – the age of forty, by his calculations – but his obsessive recollections, his seeing the world through the screen of childhood memories, remains his primary obstacle (Baker 58). The novel’s plot is built around a single event – an escalator ride – during an ordinary day five years prior to the novel’s present (its fictional time of writing). At that time, Howie worked at an unnamed corporation and takes us from his lunch break back to his office on the building’s mezzanine, with the escalator ride serving as the focal point. In a narrative where there are more tangents than forward motion, a reader might become overwhelmed with the apparently superfluous anecdotes, but these memories, meditations, and observations – and Baker’s seamless segues between them – are the real magic of The Mezzanine.

The story begins as the Howie’s lunch hour is ending and he is approaching the escalator leading to the mezzanine of his office building. Howie is an obsessive, voracious observer of the world around him and delights in sharing his observations in this “memoir.” Mid-way through the second paragraph he digresses to inform us about his activities during his lunch hour, including a two-page-long footnote on the history of drinking straws. Thus, it becomes clear early that this escalator ride is going to take some time to complete; indeed, it will take the remainder of this engaging and richly imagined novel. By chapter five Howie hasn’t even stepped onto the escalator; the story has focused on his past. The first paragraph of chapter five is composed of three short sentences and one long cumulative sentence (341 words) that enumerates Howie’s favorite “systems of local transport” as a child, including rotisseries, rotating watch displays, hot dog cookers, and, of course, escalators:

Other people remember liking boats, cars, trains, or planes when they were children – and I liked them too – but I was more interested in systems of local transport: airport luggage-handling systems (those overlapping new moons of hard rubber that allowed the moving track to turn a corner, neatly drawing its freight of compressed clothing with it; and the fringe of rubber strips that marked the transition between the bright inside world of baggage claim and the outside world of low-clearance vehicles and men in blue outfits); supermarket checkout conveyor belts, turned on and off like sewing machines by a foot pedal, with a seam like a zipper that kept reappearing; and supermarket roller coasters made of rows of vertical rollers arranged in a U curve over which the gray plastic numbered containers that held your bagged and paid-for groceries would slide out a flapped gateway to the outside; milk-bottling machines we saw on field trips that hurried the queueing [sic] bottles on curved tracks with rubber-edged side-rollers toward the machine that socked milk into them and clamped them with a paper cap; marble chutes; Olympic luge and bobsled tracks; the hanger-management systems at the dry cleaner’s – sinuous circuits of rustling plastics (NOT A TOY! NOT A TOY! NOT A TOY!) and dimly visible clothing that looped from the customer counter way back to the pressing machines in the rear of the store, fanning sideways as they slalomed around old men at antique sewing machines who were making sense of the heap of random pairs of pants pinned with little notes; laundry lines that cranked clothes out over empty space and cranked them back in when the laundry was dry; the barbecue-chicken display at Woolworth’s that rotated whole orange-golden chickens on pivoting skewers; and the rotating Timex watch displays, each watch box open like a clam; the cylindrical roller-cookers on which hot dogs slowly turned in the opposite direction to the rollers, blistering; gears that (as my father explained it) in their greased intersection modified forces and sent them on their way. (35-36)

Howie follows this long catalogue with a short sentence, telling us that the escalator shared qualities with these systems with one notable exception: he could ride the escalator. This telescopes his childhood obsession into adulthood – he can, after all, still ride escalators – where the escalators stimulate Proustian involuntary memories of childhood including, he tells us, memories of his and his father’s shared “mechanical enthusiasms” and of the specific memory of his mother taking him and his sister to department stores and instructing them on escalator safety. This memory, in turn, stirs his concern that he spends too much time (in the present of his writing, not the time of his riding the escalator) thinking of things exclusively in terms of his childhood memories, an epiphany that sets up the last paragraph, a précis for the novel:

I want . . . to set the escalator to the mezzanine against a clean mental background as something fine and worth my adult time to think about . . . I will try not to glide on the reminiscential tone, as if only children had the capacity for wonderment at this great contrivance.[2] (39-40)

True to his digressive tendencies, however, the escalator won’t be mentioned again until chapter eight, and it is not until the midpoint in the novel that Howie actually boards the escalator.

Baker’s long list sentence adds character detail to this dense tale. First, note his eye for specifics: the “blistering” of the hot dogs, the “men in blue” at the airport. Second, he uses metaphor and simile: the “new moons of hard rubber” and watch boxes “like open clams.” Thus, the list not only informs on Howie’s whimsical, yet poetic and reflective nature, but also shows us, by example, his obsessive behavior. Howie acknowledges he likes the things other children liked, only he liked something else more, something odd, something unusual; and then he shows us how much it all meant to him with his detailed recollection. Once Howie begins his recollection, he becomes lost in it; his list goes on and on and he can hardly break free from its hold on him as new things are added and elaborated in fractal-like digressions. Howie spirals into many such lavishly detailed memories and the long sentences convey his sense of being lost in contemplation. Despite his continuing attempts to escape the gravitational pull of his childhood, Howie keeps being drawn deep into memory. A convincing stylistic choice, this long list sentence adds detail while simultaneously revealing character through syntactic symbolism – the long, uninterrupted flow of Howie’s list shows us his obsession with his childhood.

/

Motion Mimesis

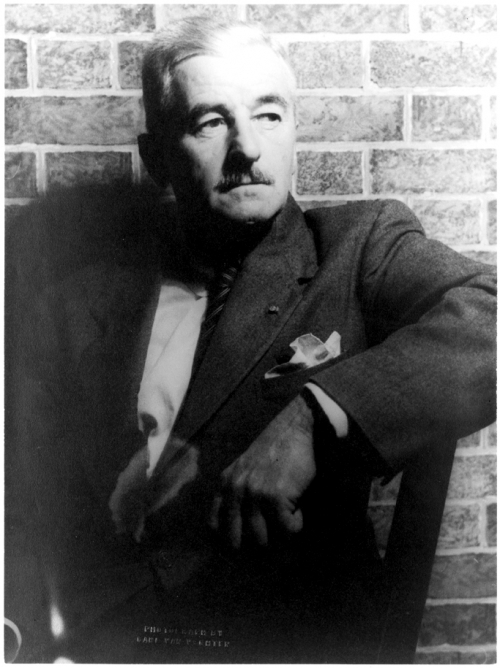

Syntagmatic extension of a sentence always has one consequence: it keeps the reader in the moment. Except for perhaps sentences that run for pages, most readers will read to the end of a long sentence before making a full stop at the period. Dwelling on the action can have several effects depending on the subject, including heightening the emotional impact of the moment, whether that is grief or joy, ecstasy or terror. When actions are depicted by the sentence, the rhythm of the prose can lend itself to mimicking the character’s movement. An excellent example of such motion mimesis is found in the climax of William Faulkner’s 1939 short story “Barn Burning.”

“Barn Burning” is a coming-of-age story set in the post-Civil War American South. The 23-page story has a linear timeline, is written in the past tense, and covers six days, from a Monday through a Saturday. The third-person limited point of view focuses on the thoughts of the protagonist, the ten-year-old Colonel Sartoris “Sarty” Snopes, youngest of the four Snopes children. The paterfamilias, Abner Snopes, is a violent sociopath, and at the beginning of the story he is a suspect in the burning of a barn. After being found not guilty, he loads up his family for the twelfth time in ten years and moves to the next hamlet to find a work on a farm. The day they arrive Snopes indulges his hatred and jealousy by going to the house of the landowner Major de Spain and deliberately soiling an expensive carpet with horse manure. When asked to clean the rug, Snopes destroys it in the process. In court for the second time within a week, Snopes is fined ten bushels of corn; enraged, that night he sets out to burn de Spain’s barn. When he sees that Sarty is shocked, he becomes worried that his son will thwart his plans and has him held back by his mother. After Snopes and the older son leave, Sarty breaks loose and runs to the de Spain mansion where he bursts in and warns them of the imminent arson. Sarty flees down the road toward the barn and is soon passed by de Spain on horseback. Hearing three shots, Sarty believes his father dead and runs away, leaving his family forever. The primary image of “Barn Burning” is “blood,” which Faulkner uses eight times and always in the context of Sarty and his father or family. In the climax Sarty must choose between his father, his blood, and what he feels is the moral, right choice of warning de Spain.

Young Sartoris has an apparently instinctive sense of right and wrong that jars with his father’s violent, malicious behavior. In the opening scene when his father is before “the Justice,” the boy knows his father is guilty: “He aims for me to lie, he thought, again with that frantic grief and despair. And I will have to do hit” (Faulkner 4); and two days later, after his father is told by Major de Spain that he’ll have to pay twenty bushels of corn for destroying the rug, Sarty, working in the field, hopes that this will mark the end of his father’s reign of terror; he thinks: “Maybe it will all add up and balance and vanish – corn, rug, fire; the terror and grief, the being pulled two ways like between two teams of horses – gone, done with for ever and ever” (17). He can’t believe it when his father tells him to get the oil; he knows what his father intends to do. As Sarty is fleeing down the road after warning de Spain, his “blood and breath roaring,” he is in a semi-fugue state:

He could not hear either: the galloping mare was almost upon him before he heard her, and even then he held his course, as if the very urgency of his wild grief and need must in a moment more find him wings, waiting until the ultimate instant to hurl himself aside and into the weed-choked roadside ditch as the horse thundered past and on, for an instant in furious silhouette against the stars, the tranquil early summer night sky which, even before the shape of the horse and rider vanished, stained abruptly and violently upward: a long, swirling roar incredible and soundless, blotting the stars, and he springing up and into the road again, running again, knowing it was too late yet still running even after he heard the shot and, an instant later, two shots, pausing now without knowing he had ceased to run, crying “Pap! Pap!”, running again before he knew he had begun to run, stumbling, tripping over something and scrabbling up again without ceasing to run, looking backward over his shoulder at the glare as he got up, running on among the invisible trees, panting, sobbing, “Father! Father!” (24)

The motion described by the sentence begins with de Spain’s galloping mare gaining on Sarty and continues with him flinging himself into the ditch. After the stunning pause with the juxtaposition of “furious silhouette” and “tranquil . . . night sky (“stained” as blood stains), the motion then gathers momentum as Sarty resumes his sprint. What follows are sixteen more verbs, mostly action verbs, expressed as present participles[3] (as opposed to the past definite). This creates a sense of simultaneity and continuous motion. Faulkner repeats “running” four times and “run” twice within the second half of the sentence; this emphasis extends beyond the motion it is describing to become a metaphor for Sarty and his future. Following the gunshots, he pauses briefly crying the familiar “Pap! Pap!” – his blood; his blood now severed he resumes his run but now he is running away as he had imagined when his father asked him to get the oil: “I could run on and on and never look back . . .” (21). This horrible moment, the defining moment of Sarty’s life, when the choice he made results in the death (at least as far as he can tell) of his father, this desperate race, is captured wonderfully by the Faulkner’s long sentence. The reader is held in suspense as the Sarty runs toward his father and as de Spain rushes to defend his property and is finally swept along with the boy as he runs and runs, never to look back.

/

The Never-ending Story

As anyone who has ever listened to a speech knows, there is a rhythm to the spoken word. A speaker may drone on and on and put the audience to sleep, or he can be dynamic, lyrical, and modulate his tone to keep the audience’s attention. Generally we need pauses in a speech; they are necessary moments of reflection and break the monotony of an unchanging cadence. Aside from soliloquy, fictional characters rarely have unmitigated speech; otherwise the writer, like the droning speaker, might lose his audience. So it is intriguing to find a writer who is willing to take up the challenge of writing a continuous monologue without chapters, without section breaks or line breaks; indeed a monologue as a single sentence that captures the rhythm of language while still entertaining the reader. Such is Bohumil Hrabal’s Dancing Lessons for the Advanced in Age.

First published in Czechoslovakia in 1964 and in an English translation by Michael Henry Heim in 2011, Hrabal’s single-sentence book defies categorization. His friend and reviewer Josef Sǩvorecký called it a “long short story” (Sǩvorecký 7). Adam Thirlwell, who wrote the introduction for the 2011 edition, called it a “novel in one monologue” (Hrabal viii). Semantics aside, this unique story, or collection of tall tales, is a wonderful example of how a writer can sculpt a very long, yet engaging sentence that mimics the spoken word. Hrabal developed his style of story-telling, what he called páblitelé – which Sǩvorecký translates as “tellers of tall tales” and which Thirlwell translates as “palavering” – based on the free-association rambling of oral story-tellers in his life. But this is not a form of automatic writing or free writing – genuine craft is expressed in Hrabal’s prose; the narrator’s monologue (it isn’t really a speech – speeches are organized logically and are intended to communicate specific information – neither of which applies here) is by degrees whimsical, ribald, lyrical, poignant, and profound.

Superficially, the book represents the uninterrupted speech of a septuagenarian shoemaker named Jirka who is regaling a group of sunbathing women with his stories of being a soldier during the Austro-Hungarian monarchy, his sexual exploits, his opinions on the church and religion, and his humorous digressions of tall tales. It is told in the first-person, mostly in the past tense, and follows real time in that the amount of time it takes to read the 117 pages approximates the time it would take to actually listen to the narrative. Jirka’s desire is to be listened to, to flirt with the ladies; his conflict is keeping his listeners’ attention. But unlike a random, garrulous old man droning on and on, one who won’t let you go until you hear every variation of the same big fish story, Jirka keeps us listening:

neither Havlíček nor Christ ever laughed, if anything they wept, because when you stand for a great idea you can’t horse around, Havlíček had a brain like a diamond, the professors went gaga over him, they tried to make him a bishop, but no, he chose justice, a little coffee, a little wine, and a life for the people, stamping out illiteracy, only perverse people dream of rolling in manure (better days ahead) or of chamber pots (your future is assured) because the thing is, dear ladies, you’ve got to rely on yourselves, take Manouch, who thought he had it made because his father was a jailer and all he did was drink and pick up bad habits, which leads to fights like the quarrel in the days of the monarchy between the social democrats and the freethinkers and clerics over whether the world comes from a monkey or God slapped Adam together out of mud and fashioned Eve from his insides, now He could have made her out of mud too, it would have been cheaper, though nobody really knows what went on, the world was as deserted as a star, but people twitter away like magpies and don’t really care, I could set my sights on a charmer, a prime minister’s daughter, but what’s not to be is not to be and could even take a bad turn, Mother of God! the crown prince had syphilis and that Vetsera woman shot him, but then she got shot by the coachman, though any young lady will tell you you might as well be buried alive if the man in your life has a faulty fandangle, when I was serving in the most elegant army in the world I told our medical officer, Doctor, I said, I’ve got a weak heart, but all he said was, So have I, boy, and if we had a hundred thousand like you we could conquer the world, and he put me into the highest category, so I was a hero . . . (3-5)

For the purposes of this essay I’ve selected this 340-word excerpt of the 117-page long sentence so that a sense of the rhythm can be appreciated. In the book as a whole, after the comma, the most common punctuation mark Hrabal uses is the question mark, then the dash, then the exclamation point; there are no colons or periods (even at the end) and only one semicolon.

In this relatively short passage there is an astonishing variety of subjects. He begins with philosophizing about the writer Havlíček and Christ (a favorite subject); then makes an aphoristic statement (a common habit); he reflects on Havlíček’s history with clear parallels to his own (Jirka’s) values; he quotes ironic entries from his favorite book of dream interpretations, refers to his audience, and then drops another aphorism. He interrupts himself at one point with the exclamation “Mother of God!” (another habit) indicating that he has just remembered something that he absolutely must tell the ladies right away. Note that Hrabal doesn’t let us forget the scene: more than a dozen times in the book Jirka refers directly to the women he is speaking to, but here he also says “though any young lady will tell you,” an indirect nod in their direction and a preface to his flirting. He concludes this part of his never-ending sentence with a tale of the absurd, a lampoon of his time in the military (another favorite subject).

Sǩvorecký writes that Hrabal’s importance “lies predominantly in this language, in how his stories are told” (8). The book’s forward momentum is carried by Jirka’s engaging voice and the bizarre, often humorous tales he tells. Narrative voice isn’t carried by subject matter and diction alone, but by the order of words, i.e. the syntax with which those words are arranged.

/

The Persistence of Thought: Mind Mimesis

One of the most elusive subjects in fiction, as in life, is the nature of human consciousness. Philosophers have been arguing about how we know (or think we know) what we know and how we know what others know since the emergence of language. Epistemological questions aside, how can a writer convey – or attempt to convey – the nature of human thought?

Methods for representing a character’s thought span the range of narrative modes. Consider first-person. It seems straightforward enough: have the character simply tell us what he is thinking. When addressing another character, this is dialogue, or if alone, a soliloquy. Soliloquy typically follows the rules of grammar and is logically organized. And soliloquy, although spoken alone, is presented as if to an audience, which requires it to be more coherent (Humphrey 35). But what if the language is internal self-address, i.e. the language we “speak” only to ourselves? The narrative mode used to describe this is variously called free direct thought, internal monologue, or autonomous monologue. Interior monologue, in contrast to soliloquy (or dialogue) is more associative; prone to spontaneous, illogical shifts; and is rich in imagery (Cohn 12). The acme of internal monologue in literature is found in the “Penelope” chapter of James Joyce’s Ulysses.

James Joyce’s 1922 Ulysses is the ur-text for modernism. Published in 1922, this canonical “stream of consciousness” novel is the story of the lives of three principal characters, Leopold Bloom (who works in advertising), his wife Molly (a professional singer), and a family friend Stephen Dedalus (an aspiring poet) on a single day: June 16, 1904. The book is divided into eighteen sections and is organized according to Homer’s Odyssey, with Bloom in the role of Odysseus (Ulysses in Roman myths). Bloom’s journey takes him from home, through his day in Dublin, and then back again; along the way he is joined by Stephen. Almost all of the chapters focus on Bloom, but the last chapter, commonly referred to as “Penelope” in reference to Odysseus’s wife, takes place in the mind of Molly while she tosses and turns, unable to fall asleep after her husband returns home and joins her in bed at approximately two in the morning. “Penelope” is divided into eight “sentences,” although the only reason for designating them thusly are line breaks with indentation; the chapter has no punctuation except for two periods, one at the end of the fourth sentence; one at the end. The run-on nature of the chapter is the point, that thought doesn’t stop; it keeps flowing in an endless stream until you either fall asleep (except for dreaming) or die, i.e. you can’t turn thought off.

Molly has had a singular day: she has had an affair with her manager Hugh “Blazes” Boylan. Lying awake in bed, her thoughts roam: she thinks about Boylan and compares his sexuality with Bloom’s; she thinks about her marriage and that she and “Poldy” (whom she suspects has had an affair too that day) haven’t have sex since their son Rudy died shortly after he was born eleven years prior; she thinks about the future and is worried about their finances, she fantasizes about the twenty-something Stephen; and she thinks about her past, including the men she has known, her childhood in Gibraltar, and (famously) when Bloom asked her to marry him and she said yes. The only indication of an external world is a train whistle she hears; the only action, when she gets out of bed to use the chamber pot. Molly’s character is highly nuanced and through her unedited stream of consciousness the reader empathizes with the conflicts she faces in her life. After her fantasy of seducing Stephen concludes, her thoughts turn back to Boylan, then to Bloom as the last sentence of the chapter begins. She is annoyed with Bloom for having kissed her bottom after he crawled into bed. Her annoyance leads to sexual fantasies with other men until she is distracted by Bloom crowding her on the bed; she thinks:

O move over your big carcass out of that for the love of Mike listen to him the winds that waft my sighs to thee[4] so well he may sleep and sigh the great Suggester Don Poldo de la Flora if he knew how he came out on the cards this morning hed have something to sigh for a dark man in some perplexity between 2 7s too in prison for Lord knows what he does that I dont know and Im to be slooching around down in the kitchen to get his lordship his breakfast while hes rolled up like a mummy will I indeed did you ever see me running Id just like to see myself at it show them attention and they treat you like dirt I dont care what anybody says itd be much better for the world to be governed by the women in it you wouldnt see women going and killing one another and slaughtering when do you ever see women rolling around drunk like they do or gambling every penny they have and losing it on horses yes because a woman whatever she does she knows where to stop sure they wouldn’t be in the world at all only for us they dont know what it is to be a woman and a mother how could they where would they all of them be if they hadnt all a mother to look after them what I never had thats why I suppose hes running wild now out at night away from his books and studies and not living at home on account of the usual rowy house I suppose well its a poor case that those that have a fine son like that theyre not satisfied and I none was he not able to make one it wasnt my fault we came together when I was watching the two dogs up in her behind in the middle of the naked street that disheartened me altogether I suppose I oughtnt to have buried him in that little woolly jacket I knitted crying as I was but give it to some poor child but I knew well Id never have another our 1st death too it was we were never the same since O Im not going to think myself into the glooms about that any more . . . (778)

This 392-word excerpt depicts the silent, unmediated self-communication of a fictional mind saturated with thoughts that transition associatively with dizzying speed. She is annoyed at Bloom for hogging the bed; she compares his wheezing (or perhaps snoring) with a song called “The Winds That Waft My Sighs to Thee” (remember, she is a professional singer; she doesn’t “say” to herself “His snoring sounds like X, rather the association pops into her consciousness as she listens to him breathe); she invents an epithet for Bloom; she thinks about the card reading she did for him; she’s aggravated about agreeing to fix him breakfast; she philosophizes about what a better world it would be if “governed by the women”; she reflects that men are ungrateful and then thinks of Stephen, whom she worries about in a maternal way; she speculates that Stephen’s parents don’t appreciate him and that they are ungrateful which leads to her thoughts of her dead son Rudy and that she should have given the coat she knitted for him to a needy child; and she reflects that she and Bloom haven’t been intimate since Rudy’s death, which she then resolves not to be depressed about. She uses the imperative (“O move over”), indicative (“I dont care what anybody says”), and subjunctive (“if he knew”) mood. She uses the past, present, and future tense. And all of these grammatical forms are switched between with the fluid rhythmicity of thought.

The first and most obvious feature of this excerpt that adds to its verisimilitude as internal monologue is the fact that it is uninterrupted; there are no gaps in the text as there are no gaps in our thoughts. Another feature of “pure” internal monologue that makes this example (and the entire “Penelope” chapter) successful as speech-for-oneself is the use of non-referential pronouns, i.e. “he” refers to Bloom, Stephen, and Rudy at different places in the stream of thought, and, significantly, there is no immediate reference to whom of the three she is thinking about. After all, Molly knows who she is thinking about and doesn’t need to explain it to anyone – this isn’t a soliloquy, this isn’t a speech, and this isn’t dialogue. Finally, the thought mimesis isn’t disrupted by Molly reporting her actions using action verbs and the first-person pronoun. This last quality doesn’t apply particularly to this passage, but it is important to the success of the chapter as a whole. The only action she takes is to use the chamber pot and Joyce is careful to address her kinetic perceptions without action verbs (q.v. sub).

.

Mathias Énard’s Zone, published in France in 2008 and in an English translation by Charlotte Mandell in 2010, is a novel that parallels Ulysses in many ways. Like Joyce, Énard borrowed his structure from Homer, this time: The Iliad. Also like Joyce, Énard explores consciousness with internal monologue. With Zone Énard follows the tradition of novel-length sentences such as those by Bohumil Hrabal, Jerzy Andrzejewski, and Camilo José Cela. Zone is presented as a single-sentence internal monologue by the protagonist Francis Servain Mirković, a former spy for French Intelligence, now fleeing to a new life aboard a train from Milan to Rome. However, the sentence is interrupted by twenty-four, numbered chapter divisions (loosely reflecting Homer’s epic), and three chapters are devoted to a tale-within-the-tale (a book Francis is reading in which the plot parallels his own). Neither the parallel story, nor the chapter breaks detract significantly from the continuity of Francis’s roaming thoughts, and the stylistic choice of an internal monologue allows Énard great freedom in creating an intricate network of associated images.

The novel begins in media mentum in Francis’s mind as the train is leaving the Milan station: “everything is harder once you reach man’s estate, everything rings falser a little metallic like the sound of two bronze weapons clashing . . .” (Énard 5). Two bronze weapons clashing. Énard’s war imagery begins immediately and doesn’t relent. Francis, Croatian veteran of the Bosnian War, amateur historian, spy, has fled France with a suitcase full of war crimes information. He plans to sell the documents to the Vatican for $300,000, his nest egg for retirement under an assumed identity. The story of a man trying to escape his past, Zone is told from Francis’s point of view in internal monologue, but with the psychic distance shifted toward autobiography and reportage, i.e. with thoughts organized more logically than Joyce presents Molly’s meditations. Francis, in his recollections, tells a story, or many stories, during his trip. Francis never leaves the train, although the locations he passes serve as segues for his mental peregrinations through history (personal and otherwise), especially of wars in the Mediterranean region.

Dorrit Cohn, in her 1978 seminal work Transparent Minds, notes that “unity of place . . . creates the conditions for a monologue in which the mind is its own place . . .” (222) and compliments Joyce on his decision to place Molly in bed where she doesn’t need to address her kinetic perceptions. Of course, that isn’t entirely accurate since Molly does get out of bed to use the chamber pot. Énard also places his character in a position of stasis, the train seat he occupies for the trip, and, like Molly, Francis will get up and move about only briefly. However, Énard gets to have it both ways: yes, Francis is static (most of the time) but he is also on a moving train passing through the Italian countryside and through Italian cities – opportunities for Francis’s thoughts to segue between subjects. Sometimes Francis only notes the city without comment, such as when he passes through Parma and Reggio Emilia, but other times he uses the location as a platform to digress about history, or to facilitate his meditations. As the train pulls out of Florence, Francis thinks:

I’m facing my destination, Rome is in front of me, Florence streams past, noble Florence scattered with cupolas where they blithely tortured Savonarola and Machiavelli, torture for the pleasure of it strappado water the thumb-screw and flaying, the politician-monk was too virtuous, Savonarola the austere forbade whores books pleasures drink games which especially annoyed Pope Alexander VI Borgia the fornicator from Xàtiva with his countless descendants, ah those were the days, today the Polish pontiff trembling immortal and infallible has just finished his speech on the Piazza di Spagna, I doubt he has children, I doubt it, my neighbors the crossword-loving musicians are also talking about Florence, I hear Firenze Firenze one of the few Italian words I know, in my Venetian solitude I didn’t learn much of the language of Dante the hook-nosed eschatologist, Ghassan and I spoke French, Marianne too of course, in my long solitary wanderings as a depressed warrior I didn’t talk with anyone, aside from asking for a red or white wine according to my mood at the time, ombra rossa or bianca, a red or white shadow, the name the Venetians give the little glass of wine you drink from five o’clock onwards, I don’t know the explanation for this pretty poetic expression, go have a shadow, as opposed to going to take some sun I suppose at the time I abused the shadow and night in solitude, after burning my uniforms and trying to forget Andi Vlaho Croatia Bosnia bodies wounds the smell of death I was in a pointless airlock between two worlds, in a city without a city, without cars, without noise, veined with dark water traveled by tourists eaten away by the history of its greatness . . . (330-331) [Énard’s italics]

One of the first things to note is that the internal monologue is more conversational, more dialogic than Molly’s internal speech. Joyce’s style eschews active verbs and punctuation, giving it a less edited and more organic feel. But such a style would be difficult to maintain for the 517-page journey Zone follows; “Penelope” is just over 40 pages. Énard’s more coherent syntax is more readable and more forgiving. Nevertheless, the sentence (fragment) succeeds in capturing the flowing thoughts of the character using many of the same techniques used by Joyce including: omitting punctuation (in places), rapid and spontaneous free association, staccato rhythms, and poetic imagery.

Francis’s thoughts flow in free association when the thought of torture triggers a list of torture techniques including strappado, the use of water, and thumb-screws; here the absence of commas, definite articles, or other grammatical devices helps create the stream of consciousness effect. In this 286-word excerpt Francis then: generalizes ironically about the past (“those were the days”), has doubts, observes his fellow travelers, thinks of the languages he knows and once spoke with a friend and his ex-girlfriend, reflects on the present in generalizations, and finally returns to his past where the names of his fellow soldiers and friends run together with locations, trailing off in poetic imagery.

There are three notable differences between this monologue and the type of pure internal monologue seen in the Joyce example. First, it is broken up with punctuation. Second, Énard uses referential pronouns, e.g. Xàtiva/his and pontiff/his, and people have proper names. Third, the thought mimesis is interrupted by Francis’s declaring his perceptions using action verbs and the first-person pronoun, e.g. “I hear Firenze Firenze” – Molly hears a train, but she never tells the reader. This last difference is significant for action depiction as well.

Both Molly and Francis act in their memories, whether it is Molly musing about her first sexual encounter in Gibraltar or Francis reliving the horror of watching his friend get shot in Bosnia. But for movement in the narrative’s present, internal monologue can be difficult to manage without disturbing the reader’s perception, i.e. if the reader has accepted that they are “listening in” to someone’s thoughts then describing external events can be as jarring as changing the point of view. For example: one of the distinctive features of pure internal monologue is that thought isn’t disrupted by characters reporting their actions using action verbs and the first-person pronoun. In the following excerpt, Molly gets out of bed to urinate and find a sanitary napkin, but we only read her impressions:

O Jamesy let me up out of this pooh sweets of sin whoever suggested that business for women what between clothes and cooking and children this damned old bed too jingling like the dickens I suppose they could hear us away over the other side of the park till I suggested to put the quilt on the floor with the pillow under my bottom I wonder is it nicer in the day I think it is easy I think Ill cut all this hair off me there scalding me I might look like a young girl wouldnt he get the great suckin the next time he turned up my clothes on me Id give anything to see his face wheres the chamber gone easy Ive a holy horror of its breaking under me after that old commode I wonder was I too heavy . . . (769)

In the first line, where we expect the word “bed,” we find the interjection “pooh” – a word that has spontaneously popped into her consciousness. There is a missing copula in “this damned old bed too jingling.” She never “thinks” she is walking to the chamber pot, only wonders where it has gone. Compare this with the following passage from Zone where Francis describes going to the toilet:

I’d like to go have a drink at the bar, I’m thirsty, it’s too early, at this rate if I begin drinking now I’ll arrive in Rome dead drunk, my body is weighing me down I shift it on the seat I get up hesitate for an instant head for the toilet it’s good to move a little and even better to run warm non-potable water over your face, the john is like the train, modern, brushed grey steel and black plastic, elegant like some handheld weapon, more water on my face and now I’m perked up, I go back to my seat . . . (54)

Note the first-person pronoun and action verb use: “I shift it,” “I get up,” and “I go back.” There are three constructions using copulas (or implied copulas): “it’s too early,” “it’s good,” and “the john is.” As a result of the action verbs and copulas, what should be internal monologue feels like reportage.

Nevertheless, Énard demonstrates the versatility of a long sentence internal monologue. I agree with Mary Stein, who wrote in her 2011 review of Zone: “Énard’s ambitious prose functions as a structure necessary to and inseparable from Mirković’s narrative identity.” The stream of consciousness fluidity of the long run-on sentence mimics Francis Mirković’s disturbed mind, and if some verisimilitude of consciousness mimesis is sacrificed, his narrative identity still supports a web of imagery that rises to the level of great art.

/

Altered States

Infinite Jest, David Foster Wallace’s sprawling 1996 novel, opens during the Year of Glad (ca. 2008) in an imagined future where the U.S., Canada, and Mexico have been combined into the Organization of North American Nations (O.N.A.N.) and corporations purchase naming rights to each calendar year. Three interwoven plots follow separate groups of characters, including: the protagonist Hal Incandenza and his schoolmates at the Enfield Tennis Academy in Boston, a group of men and women in a drug rehabilitation house nearby, and a Québécois terrorist group.

Most of the action of the novel takes place one year prior to the opening scene and is narrated in the past tense by, arguably, Hal. The novel, told primarily from a third-person point of view, has numerous examples of first-person intrusion, and it is always Hal. Hal is a linguistic prodigy, and his way of interpreting the world is revealed in a stylistic manner consistent with his consciousness, i.e. with elevated diction and complex syntax. Hal is also a drug addict. In fact, many of the characters have substance abuse issues and Infinite Jest is in many regards the epic of addiction. During Hal’s senior year at his private high school he struggles with marijuana addiction while, simultaneously, Joelle Van Dyne struggles with cocaine. Joelle is the ex-girlfriend of Hal’s older brother Orin and, after her near-fatal overdose, becomes a resident of the rehab house near Hal’s school.

Although Wallace depicts the consciousness of his characters almost exclusively using third-person narration, he still achieves a stream of consciousness effect in many scenes. The problem with first-person presentation of characters in drug-induced states of altered consciousness is that, as readers, we neither expect them to speak in coherent language, nor can we imagine any coherence to their thoughts at all. Thus, Cohn writes that “the novelist who wishes to portray the least conscious strata of psychic life is forced to do so by way of the most indirect and the most traditional of the available modes” (56), what she terms “psycho-narration” (or third-person narration). Wallace makes effective use of long sentences to depict altered conscious states in the scenes of Joelle’s overdose and Hal’s nightmare.

Joelle, who has a late-night radio show, was disfigured some years before when acid was thrown in her face. She now wears a veil and is a member of the “Union of the Hideously and Improbably Deformed.” Early in the primary timeline, Joelle[5] returns to the apartment she shares with Molly (who is throwing a massive party), locks herself in the bathroom, and proceeds to commit suicide by smoking freebase cocaine. The following 449-word long sentence is from her point of view and takes place after her second dose from her homemade pipe:

The voice is the young post-New Formalist from Pittsburgh who affects Continental and wears an ascot that won’t stay tight, with that hesitant knocking of when you know perfectly well someone’s in there, the bathroom door composed of thirty-six that’s three times a lengthwise twelve recessed two-bevelled squares in a warped rectangle of steam-softened wood, not quite white, the bottom outside corner right here raw wood and mangled from hitting the cabinets’ bottom drawer’s wicked metal knob, through the door and offset ‘Red’ and glowering actors and calendar and very crowded scene and pubic spiral of pale blue smoke from the elephant-colored rubble of ash and little blackened chunks in the foil funnel’s cone, the smoke’s baby-blanket blue that’s sent her sliding down along the wall past knotted washcloth, towel rack, blood-flower wallpaper and intricately grimed electrical outlet, the light sharp bitter tint of a heated sky’s blue that’s left her uprightly fetal with chin on knees in yet another North American bathroom, deveiled, too pretty for words, maybe the Prettiest Girl Of All Time (Prettiest G.O.A.T.), knees to chest, slew-footed by the radiant chill of the claw-footed tub’s porcelain, Molly’s had somebody lacquer the tub in blue, lacquer, she’s holding the bottle, recalling vividly its slogan for the last generation was The Choice of a Nude Generation, when she was of back-pocket height and prettier by far than any of the peach-colored titans they’d gazed up at, his hand in her lap her hand in the box and rooting down past candy for the Prize, more fun way too much fun inside her veil on the counter above her, the stuff in the funnel exhausted though it’s still smoking thinly, its graph reaching its highest spiked prick, peak, the arrow’s best descent, so good she can’t stand it and reaches out for the cold tub’s rim’s cold edge to pull herself up as the white-party-noise reaches, for her, the sort of stereophonic precipice of volume to teeter on just before the speakers blow, people barely twitching and conversations strettoing against a ghastly old pre-Carter thing saying ‘We’ve Only Just Begun,’ Joelle’s limbs have been removed to a distance where their acknowledgment of her commands seems like magic, both clogs simply gone, nowhere in sight, and socks oddly wet, pulls her face up to face the unclean medicine-cabinet mirror, twin roses of flame still hanging in the glass’s corner, hair of the flame she’s eaten now trailing like the legs of wasps through the air of the glass she uses to locate the de-faced veil and what’s inside it, loading up the cone again, the ashes from the last load make the world’s best filter: this is a fact. (239-240)

Joelle’s overdose results in an altered state of consciousness. Wallace begins the descent into her mind with a complete sentence of indirect internal monologue: she hears someone asking if the bathroom is occupied The voice . . . in there”). Rather than ending this sentence with a period, Wallace creates a run-on sentence with several clauses that describe her perceptions using vivid imagery (e.g. adjectives like beveled, warped, steam-softened, raw, and mangled). About halfway through the sentence she thinks of the nickname Orin gave her. The next clause is a complete sentence and internal monologue: “Molly’s had somebody lacquer the tub in blue,” followed by a single-word thought (“lacquer”), and then the narration shifts back to third-person (or perhaps indirect internal monologue) with “she’s holding the bottle.” There are memories, then more sensory descriptions (sound is now white noise); she regards her limbs as distant, has lost her shoes, is lost in hallucination (“twin roses of flame still hanging in the glass’s corner”), and finally reloads her pipe for another dose. The long, run-on nature of this sentence; the free associations; the irrational switching between perceptions, actions, and thoughts; and the poetic imagery all contribute to creating a stream of consciousness effect in this passage.

Conveying a dream state presents the writer with the same problem of drug-induced states: it is subliminal thought. Hal’s nightmare of finding “Evil” in his dorm room is a tour de force of long-sentence syntax engendering suspense and depicting the process that takes place in a dreaming mind.

A subchapter begins with first-person narration during an indeterminate time, i.e. it could be outside the narrative while the implied author is writing. The narrator feels he is coming to a realization about nightmares. After letting this thought trail off in ellipsis, the narration resumes in second-person (heightening our identification with the character) as Hal (“you”) dreams that he is lying in bed in his pitch-dark dorm room. In the dream, Hal pans the room with a flashlight, listing what he sees:

The flashlight your mother name-tagged with masking tape and packed for you special pans around the institutional room: the drop-ceiling, the gray striped mattress and bulged grid of bunksprings above you, the two other bunkbeds another matte gray that won’t return light, the piles of books and compact disks and tapes and tennis gear; your disk of white light trembling like the moon on water as it plays over the identical bureaus, the recessions of closet and room’s front door, door’s frame’s bolections; the cone of light pans over fixtures, the lumpy jumbles of sleeping boys’ shadows on the snuff-white walls, the two rag throw-rugs’ ovals on the hardwood floor, black lines of baseboards’ reglets, the cracks in the venetian blinds that ooze the violet nonlight of a night with snow and just a hook of moon; the flashlight with your name in maternal cursive plays over every cm. of the walls, the rheostats, CD, InterLace poster of Tawni Kondo, phone console, desks’ TPs, the face in the floor, posters of pros, the onionskin yellow of the desklamps’ shades, the ceiling-panels’ patterns of pinholes, the grid of upper bunk’s springs, recession of closet and door, boys wrapped in blankets, slight crack like a creek’s course in the eastward ceiling discernible now, maple reglet border at seam of ceiling and walls north and south no floor has a face your flashlight showed but didn’t no never did see its eyes’ pupils set sideways and tapered like a cat’s its eyebrows’ \ / and horrid toothy smile leering right at your light all the time you’ve been scanning oh mother a face in the floor mother oh and your flashlight’s beam stabs jaggedly back for the overlooked face misses it overcorrects then centers on what you’d felt but had seen without seeing, just now, as you’d so carefully panned the light and looked, a face in the floor there all the time but unfelt by all others and unseen by you until you knew just as you felt it didn’t belong and was evil: Evil. (62) [Wallace’s italics]

The five words “the face in the floor” (following “TPs”) are embedded 26 items into the list of things Hal sees in his flashlight beam. The reader is bored when they reach “the face in the floor,” i.e. they pass right by it – as Hal does – only for it to dawn on them later (at word 224, the italicized “no”) that floors don’t have faces. Just as Hal “sees without seeing,” we read without reading. When it dawns on Hal that he has seen something that doesn’t belong, the narration shifts to a fast, frantic pace using polysyndeton and no commas (in stark contrast to the long list of comma-delineated items) as Hal searches the room for what he thinks he saw, and when he finds it, he recognizes it as “Evil.” A pictorial representation of the cat’s eyebrows adds to the subliminal quality of this part of the sentence. A short, eight-word sentence set off as a separate paragraph follows: “And then its mouth opens at your light.” The emphasis placed on this short sentence mimics the shock of being attacked in a nightmare; it is the climactic moment when dread finally becomes acute horror. Again, Cohn reminds us:

the language of . . . psycho-narration is meant to elucidate rather than to emulate the figural psyche. The narrator builds a symbolic landscape as a kind of theoretical correlative for a subliminal stratum that can never emerge on the conscious level or the verbal surface of the figural mind. (55)

Wallace shows that either the third-person or the second-person narrative mode is effective for depicting consciousness; perhaps even more so than first-person, for those modes can stretch to subconscious altered states.

***

Are long sentences necessary for every work of fiction? Absolutely not. There are many examples of beautifully written stories containing only short, simple sentences; however, the power of long sentences is undeniable when you consider the numerous ways they can be effectively applied. Capturing the rhythm of motion – whether of actions or thought or speech – using linear prose presents a challenge for every writer. Virginia Tufte and David Jauss describe an elegant solution: use syntax symbolically; allow the syntax to mimic the rhythm. Faulkner, Hrabal, Joyce, Énard, and Wallace, achieve subtle and poetic effects through the syntax of their long sentences. But their achievements with long sentences, and those of writers like Nicholson Baker, also extend to character elucidation and conveying emotional content.

In my search for examples of long sentences, I found sentences greater than 150 words in the work of over fifty authors. Some of them stay within conventional grammar (like Baker and Faulkner), while others depart from those conventions radically. The standard rules of grammar are followed for a reason, they bring coherence to our prose; too severe a departure from these rules and the text’s meaning is lost. Nevertheless, there are justifiable reasons for coloring outside the lines; especially if, in the end, you can create sentences as effective and poetic as those by the writers I’ve surveyed. Jauss counsels that “the more we concentrate on altering our syntax, the more we free ourselves to discover other modes of thought” (68), and building long sentences is certainly a dramatic way to alter our syntax.

Looking back on my meditation on the long sentence, I find it remarkable that I didn’t find a place for the writer who set me on this path, M. Proust. Turning the pages of the volume of À la recherche I’m currently rereading, Proust’s narrator describes the musician Vinteuil as:

drawing from the colours as he found them a wild joy which gave him the power to press on, to discover those [sounds] which they seemed to summon up next, ecstatic, trembling as if at a spark when sublimity sprang spontaneously from the clash of brass, panting, intoxicated, dizzy, half-madly painting his great musical fresco . . . (Proust 233)

A fitting description for the wild exuberance some writers seem to have for their long, “panting,” “intoxicated,” “dizzy,” and sometimes fully-mad sentences – writers like Proust. Too bad I didn’t have more space to write about him. Perhaps next time.

—Frank Richardson

Works Cited

Baker, Nicholson. The Mezzanine. New York: Grove Press, 1988. Print.

Bernhard, Thomas. Correction. New York: Vintage-Random, 2010. Print.

Cohn, Dorrit. Transparent Minds: Narrative Modes for Presenting Consciousness in Fiction. Princeton: Princeton UP., 1978. Print.

Énard, Mathias. Zone. Trans. Charlotte Mandell. Rochester: Open Letter, 2010. Print.

Faulkner, William. Collected Stories of William Faulkner. New York: Vintage-Random, 1995. Print

Hrabal, Bohumil. Dancing Lessons for the Advanced in Age. Trans. Michael Henry Heim. New York: New York Review of Books, 2011. Print.

Humphrey, Robert. Stream of Consciousness in the Modern Novel. Berkeley: U of California P, 1959. Print

Jauss, David. On Writing Fiction. Cincinnati: Writer’s Digest Books, 2011. Print.

Joyce, James. Ulysses. New York: Random House, 1961. Print.

Proust, Marcel. In Search of Lost Time: The Prisoner and The Fugitive. Ed. Christopher Prendergast. Trans. Carol Clark and Peter Collier. Vol. 5. London: Lane-Penguin, 2002. Print.

Sǩvorecký, Josef. “Some Contemporary Czech Prose Writers.” Novel: A Forum on Fiction 4:1 (1970): 5-13. Print.

Stein, Mary. “This Ancient World, A Review of Mathias Énard’s Zone.” Numéro Cinq 2.18 (2011): n. pg. Web.

Tufte, Virginia. Artful Sentences: Syntax as Style. Cheshire: Graphics Press, 2006. Print.

Wallace, David Foster. Infinite Jest. Boston: Little, Brown, 1996. Print.

/

Frank Richardson lives in Houston and is pursuing his MFA in Fiction at Vermont College of Fine Arts. His poetry has appeared in Black Heart Magazine, The Montucky Review, and Do Not Look At The Sun

/

- Jauss’s italics.↵

- Despite wanting to divest himself of childhood memories, he never does; even the last page includes a reference to “when I was little.”↵

- Q.v. The Mezzanine excerpt wherein eleven present participle action verbs describe the motion of the various systems of local transport.↵

- Reference to a song: “The Winds that Waft My Sighs to Thee,” by W. V. Wallace.↵

- She is known also by the epithet “The Prettiest Girl of All Time” or “P.G.O.A.T.,” a nickname given her by Orin.↵

Well done! Cheers and all that…beautiful examination of Molly’s thoughts…Hrabal, master…Bernhard, cuts through the unfinished system of thought to explore reasons without accepting excuses…would add perhaps Claude Simon somewhere…at the top no less…his cycling through the mind and time…sorting out the momentum of cause and effect still gives no plausible answers…and harking back to Joyce, the will to speak without grammar clogging up the mist…Philippe Sollers eliding from Celine to something purely “H” and Paradisical…yes, well…done, well done

Thank you! I wanted to include Simon and read his work with great interest. There were a number of great examples I would love to have included. Perhaps for the book length version?

That sounds like a capital idea. Simon’s work is a universe unto itself. My favorite of his, “The Palace”, though I’m enthralled by them all. Best of luck,

What a wonderful essay! I read it with a mix of delight and gratitude – delight because the author has managed to articulate things I’ve been thinking about for a long time but haven’t taken the time to sort out or organize, and gratitude because I’m going to pass it along to friends who read (along with me) Proust for the first time a few months ago. Many of them were left scratching their heads about why Proust used those long sentences – this explains perfectly the why behind it. Also: Hooray, I love seeing Virginia Tufte’s work cited! She’s a hero of mine; one of my most successful lectures at VCFA used The Art of the Sentence as its baseline.

Thank you Julie!

Ah, Proust. Yes, yes, yes. And Virginia Tufte’s book is amazing – an encyclopedic investigation of the magic of sentences.