This is the second in a series of essay by Contributing Editor Julie Larios on the undersung, underappreciated, underpublicized, forgotten, unknown, unread, lost (I could go on) poets of America (and beyond). There is so much chance and luck involved in becoming a famous author and so little chance and luck to go around. Little things like birthplace, the language you write in or whether or not some bigger poet is already there taking up all the air before you arrive on the scene all fresh and anticipatory. So Julie pays homage here to the great but lesser lights, the overshadowed and underrated. Julie Larios is an especially gifted poet and writer of essays about poetry. She seems to have read everything, have a scholar’s grasp of the tradition and the culture but with a poet’s eye and ear. I cannot imagine a better psychopomp into the Land of Shades; NC is amazingly lucky to have her.

dg

—

“Sing a song of juniper / That hides the hunted mouse / And give me outdoor shadows / To haunt my indoor house” (from “Sing a Song of Juniper,” published in The Sound I Listened For, 1944.)

Robert Francis, once called “the best neglected poet” by his mentor Robert Frost, lived many years of his professional life like a maple sapling not getting enough sunlight to thrive. There must be a technical name for that condition – it has something to do with photosynthesis (turning the sunlight into growth?) or chlorophyll or damping off or root rot or….Well, I’m no arborist. But whatever the term for that pathology, the tree fails to thrive because it lives in the shade of larger trees. To carry the analogy to completion, let’s just say that Robert Frost, despite his encouragement of the younger poet, cast a very big shadow over poets living in New England in the first half of the twentieth century.

The poet and editor Louis Untermeyer, approached by Frost as a possible reader and publisher for Francis’s work, said once that Francis’s poetry “reminded me so much of Robert’s that until I learned better, I thought my leg was being pulled and Robert Francis was an alter ego Robert Frost had invented by slightly altering his last name.” It was Francis’s poem “Blue Winter” that Frost offered up to Untermeyer for consideration:

Blue Winter

Winter uses all the blues there are.

One shade of blue for water, one for ice,

Another blue for shadows over snow.

The clear or cloudy sky uses blue twice-

Both different blues. And hills row after row

Are colored blue according to how far.

You know the blue-jays double-blur device

Shows best when there are no green leaves to show.

And Sirius is a winterbluegreen star.

In fact, “Blue Winter” does sound like Frost – the focus on nature as both independent of and analogous to the human condition, the contemplative mood, the fine control of rhyme scheme, and the structure which hints at becoming a classic sonnet but is satisfied instead to end without an Elizabethan bang. The language itself falls into the iambic rhythms of “plain speech” (a quality Frost mentioned often in association with his own work); Francis even seems quite casual in places, as in his decision not to name those “different blues” in Line 5, and in his unusual repetition in Line 8 of the word “show(s)” which both opens and ends the line – that’s something we do all the time when speaking, but which a poet seldom does in a single line. Frost and Francis deliberately sought out this quality of relaxed speech to avoid the over-constructed and inflated diction of their predecessors (you can hear that sound even today in poems written by poets who mistake inflated diction for serious thought.) The words of Francis’s poem are common one- or two-syllable choices until we reach that lovely neologism “winterbluegreen” in the last line, suggesting a playfulness and an approach to words as constructed, man-made objects. That approach is more Franciscan than Frostian.

Take a look at this poem by Robert Frost:

Nothing Gold Can Stay

Nature’s first green is gold,

Her hardest hue to hold.

Her early leaf’s a flower;

But only so an hour.

Then leaf subsides to leaf.

So Eden sank to grief,

So sun goes down to day.

Nothing gold can stay.

Again, the focus on nature as a metaphor for the human condition, the contemplative mood, the iambic rhythm, the plain speech, the fine control of rhyme, the almost anti-climactic last line. Without a name attached to some of their poems, it’s difficult to tell which poet wrote them. For example:

Sheep

From where I stand the sheep stand still

As stones against the stony hill.

The stones are gray

And so are they.

And both are weatherworn and round,

Leading the eye back to the ground.

Two mingled flocks –

The sheep, the rocks.

And still no sheep stirs from its place

Or lifts its Babylonian face.

What do you think – is it Frost or is it Francis? Actually, it was written by Francis and published in his second book, Valhalla and Other Poems, in 1938. To me, it is indistinguishable from Frost.

The desire to imitate, as Francis seems to have done in his early work, is not necessarily a bad one in a young poet. By imitation a poet learns to look carefully at the technical strategies behind a particular artistic voice. Visual artists are encouraged in studio classes to imitate famous artists as they study technique. But imitation can be dangerous – as Untermeyer’s assessment of Francis’s third book of poetry (The Sound I Listened For) reveals:”It is nothing against Francis that [his poetry] resembles Frost….But we know who wrote [the poems] first.” Imitation begins to suggest a lack of personal imagination, akin to forgery.

Francis might not have felt that his poems imitated Frost so much as honored him, but reverence, too, can be dangerous. Listen to what Francis wrote in his autobiography, The Trouble with Francis, about his feelings for Frost as their professional relationship developed: “If I ask myself what it was in Frost that impressed, attracted, and fascinated me most in the years before I met him as well as in the years afterwards, the answer is power. He was a poet and he had power; the combination was striking. …He was a match for any man he ran into on the street, and usually more than a match….You had only to catch a glimpse of him anywhere to sense his solidarity, his weight, his sanity….But though the poems were the basis of his ascendancy, the man himself kept increasing and enriching that ascendancy. Unlike some poets he always seemed more than his poems, inexhaustible. What he said was fresher and terser than what others said. Like a boxer his mind stood on tiptoe for the next parry and thrust. People listened because they were too fascinated not to.”

Initially then, Francis might have been too fascinated not to listen. His early work, remarkable as it is, might have suffered in terms of theme and structure due to the powerful opinions expressed by his mentor. In his autobiography, Francis published not only the text of a letter written to him by Frost, but a facsimile of the letter, as if even the Great Man’s handwriting had a solidarity and weight that Francis could not ignore. In the letter, Frost wrote, “I am swept off my feet by the goodness of your poems this time. Ten or a dozen of them are my idea of perfection.” Imagine how Francis felt when he read that kind of praise. But isn’t there something unnerving about the idea of Frost’s “idea of perfection”? Couldn’t that intimidate a young poet who, when composing future poems, found himself asking “What will Frost think of it?” and altering the piece accordingly? There is sometimes a fine line between influence and intimidation.

My concern about Frost’s influence might sound pinched and mean. But as someone who has seen that kind of reverence for an influential teacher, and who has watched the effect of it on a wide circle of fellow students, I can say that our awe of that poet’s talent and intelligence probably kept us imitative of him for too long. It was our own fault, not his; he was nothing but generous. But his students, those who felt his “power,” as Francis describes it, sometimes neglected the development of their own idiosyncrasies in favor of his.

Compare “Blue Winter” (published in 1932) to a poem written much later in Francis’s life (listed in the “New Poems” section of his Collected Poems 1936-1976):

Yes, What?

What would earth do without her blessed boobs

her blooming bumpkins garden variety

her oafs her louts her yodeling yokels

and all her Brueghel characters

under the fat-faced moon

Her nitwits numskulls universal

nincompoops jawohl jawohl with all

their yawps burps beers guffaws

her goofs her goons her big galoots

under the red-face moon?

In that poem, Francis is both big-boned and playful, like a bear with a honey buzz. He emerges from the shadows and invites the reader to join him at play, and the language is anything but measured or contemplative – in fact, it’s positively giddy. Rhyme as a formal element has disappeared, though other poetic strategies are clear. The pronounced alliteration puts me in mind of how it feels to face several Coney Island bumpers cars – they’re impossible to avoid, slightly lowbrow, confusing, almost out of control, but you still laugh and enjoy yourself until the ride is over. So, too, with the poem. And despite the fat-faced, red-faced moon, the poem addresses no other nature than human nature.

It’s no coincidence, I think, that Robert Francis titled his fourth book of poetry, published two years after Frost died, Come Out Into the Sun. But by then Francis was no longer an emerging poet and his books did not make much of a ripple. Poet and teacher Samuel French Morse, however, got it right when he said in one of the few reviews of the book, “The quiet excitement with which one reads Come Out Into the Sun generates the conviction that Francis is considerably more than ‘a poet, minor’ as he modestly calls himself. His work has humor, as well as wit, and it may be this idiosyncrasy that accounts in part for the otherwise unaccountable neglect into which the taste-makers have allowed it to fall. On the other hand, the freshness which marks almost every poem here may derive in part from the poet’s awareness that he has nothing to live up to except his own standards of excellence: he is free to be himself in ways that the poet with the burden of reputation may not be free.” The poem Morse uses as an example of this standard of excellence is one of my favorites:

Hogwash

The tongue that mothered such a metaphor

Only the purest purist could despair of.

Nobody ever called swill sweet but isn’t

Hogwash a daisy in a field of daisies?

What besides sports and flowers could you find

To praise better than the American language?

Bruised by American foreign policy

what shall I soothe me, what defend me with

But a handful of clean unmistakable words-

Daisies, daisies, in a field of daisies?

And in the “New Poems” section of his Collected Works 1936-1976 there are even more poems headed in this playful direction, such as the following:

Poppycock

Could be a game

like battledore

and shuttlecock.

Could be.

Could be a color

red

but none of your Commy red

damn you!

Red of a cocky cock’s

cockscomb

or scarlet poppies

popping in a field of wheat.

But poppycock

after all

alas is only

poppycock.

In other words bilge

bosh

buncombe

baloney

ballyhoo from Madison A

ballyhoo from Washington DC

red-white-and-blue poppycock

Hurrah!

There are other cocks

to be sure.

Petcocks

weathercocks

barnyard cocks

bedroom cocks

cocksure

or cockunsure.

But to get back to poppycock

what a word!

God, what a word!

Just the word!

Keep your damn poems

only give me the words

they are made of.

Poppycock!

It’s as if a spring has been sprung and Francis is sailing out into the air, whistling as he flies. Yes, there is weight to what is said; the poem delivers its payload. But those exclamation marks! That full-feathered rooster-ish display! And what on earth would Frost have thought of the “purest purist”?

Francis is definitely undersung, but it’s not as if his work is unknown among poets. If you read enough poetry, you eventually make your way to some of his poems. And he got a sprinkling of fine awards. He was invited to participate as a fellow in the Breadloaf Writing Conference after the publication in 1936 of his first book, Stand with Me Here. In 1938 he received the Shelley Memorial Prize (contemporary winners include Robert Pinsky, Ron Padgett, Lucia Perillo and Yusef Komunyakaa.) But nearly twenty years elapsed before the awarding of that prize and his Rome Fellowship, and almost thirty more years passed after that honor before the Academy of American Poets named him, in 1984, the recipient of a Fellowship Award, citing his “distinguished achievement.” Philip Levine was just named the 2013 winner of this prize, and recipients in the years surrounding Francis’s award are true stars now in the world of poetry: John Ashbery, Philip Booth, Maxine Kumin, Amy Clampitt. Still, the header on Francis’s obituary in the New York Times says it all: “Robert Francis, A Poet Hailed by Frost, Dies.”

So how to explain the “unaccountable neglect” of critics and the reading public, other than to say that Robert Frost cast a big shadow? Plenty of ambitious poets make their way either in spite of or because of influential mentors.

Maybe the key word there is “ambitious.” Certainly something that contributed to Francis’s failure to ascend was his parallel failure to engage in the practical art of building a reputation. He did not hob-nob, he did not schmooze, he did not self-promote, he did not teach or become a mentor himself. Why not?

As Easily as Trees

As easily as trees have dropped

Their leaves, so easily a man,

So unreluctantly, might drop

All rags, ambitions, and regrets

Today and lie with leaves in sun.

So he might sleep while they began,

Falling or blown, to cover him.

It’s interesting that in his autobiography, Francis recalls something about ambition and reputation-building that Frost said to him: “Sitting in my home on the evening of December 10, 1950, he remarked casually that he had never lifted a finger to advance his career and that what had come to him had just come to him.” Francis apparently believed Frost, and was disappointed to read, when Frost’s letters to Louis Untermeyer were published, how far from the truth it was: “…what I had taken him to mean by not having lifted a finger was evidently not what he meant.”

Francis was also startled when Frost asked him what he did when he wasn’t writing. Francis lists the things he did for himself: “Marketing, cooking, dish-washing. Washing, ironing, mending, bed-making, floor-mopping. Gardening, grass-cutting, leaf-raking, snow-shoveling. Storm windows off and screens on, screens off and storm windows on. ….If I wanted wild grape jelly to sweeten the coming winter, I had to find and gather the wild grapes and do everything to the pouring of the hot wax….I knew I could not make my situation intelligible, and, what is more, I didn’t altogether want to. I was not proud of my incessant busyness. I could have envied the miraculous sense of leisure that Robert Frost carried around with him at all times.” It seems that a little doubt, a little bitterness, swelled up in Francis when looking back on this mentor who “never smiled in greeting me at the the door.” The leisure Frost took for granted bewildered Francis, and he admitted finally that there were many Frosts to Robert Frost. “I don’t want to be a farmer,” Frost once wrote. He also wrote, “There’s room for only one person … at the top of the steeple, and I always meant that person to be me.” He admitted to ambition of “astonishing magnitude.”

In his wonderful essay about these two poets, “Robert Frost, Robert Francis, and the Poetry of Detached Engagement,” Andrew Stambuk details Frost’s studied self-idealization by showing how carefully Frost constructed and protected the image of himself as the crusty old New England farmer who stands up to Nature’s brow-beatings. In discussing one of Frost’s most famous poems, “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening,” Stambuk says, “Frost’s evocation of ‘barrenness’ is a conscious tactic that extends to a strategy of self-idealization, whereby the poet, in shrugging off this condition and asserting his will, disguises his characteristic wariness as tough-minded resistance.” Few high school students in America have not been asked their opinions of “The Road Less Traveled” or “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening” after having been taught that Frost was the man who took the road less traveled and had “promises to keep /and miles to go” before he slept.

Stambuk goes on to say that Frost “helped shape the public’s perception of him as a tough-minded realist, one strikingly at odds with the poet who was insecure about his reputation….” Maybe Stanley Kunitz described it best: Frost’s “most successful work of the imagination was the legend he created about himself.”

Francis, on the other hand, turned away from reputation-building. He gave up his 15-year dependence on income which kept him out and about in town, teaching violin lessons; he gave up his high school teaching job after only one year, and he decided to rely exclusively on the money his poetry produced, which was meager. He lived alone for more than forty years outside Amherst in a hand-built two-room house he called “Fort Juniper.” Aside from the residential fellowships he was awarded, none of the honors he accumulated paid enough money to live on. In 1955 he was the Phi Beta Kappa poet at Tufts; in 1960, he taught for a year at Harvard. He spent one year in Italy on his fellowship from the Academy and returned ten years later after being awarded the Amy Lowell Traveling Scholarship.

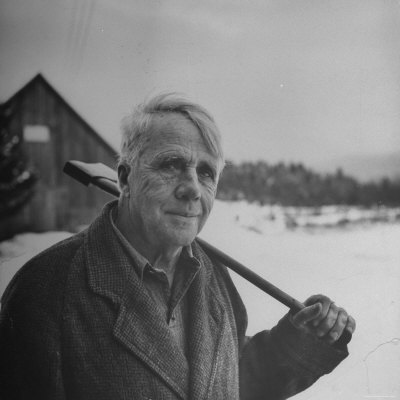

Most of Robert Francis’s life was lived Thoreau-style, in a cabin in the woods, in the shade cast not only by Robert Frost but by a suitably transcendental forest of birch trees. He died in 1987, relatively unknown, alone, 85 years old, still writing, chopping wood, sweeping the floors, ironing, mending, and making that wild grape jelly at the kitchen stove.

Come

As you are (said Death)

Come green, come gray, come white

Bring nothing at all

Unless it’s a perfectly easy

Petal or two of snow

Perhaps or a daisy

Come day, come night.

Nothing fancy now

No rose, no evening star

Come spring, come fall

Nothing but a blade of rain

Come gray, come green

As you are (said Death)

As you are.

—Julie Larios

———————————–

Julie Larios is the author of four books for children: On the Stairs (1995), Have You Ever Done That? (named one of Smithsonian Magazine’s Outstanding Children’s Books 2001), Yellow Elephant (a Book Sense Pick and Boston Globe–Horn Book Honor Book, 2006) and Imaginary Menagerie: A Book of Curious Creatures (shortlisted for the Cybil Award in Poetry, 2008). For five years she was the Poetry Editor for The Cortland Review, and her poetry for adults has been published by The Atlantic Monthly, McSweeney’s, Swink, The Georgia Review, Ploughshares, The Threepenny Review, Field, and others. She is the recipient of an Academy of American Poets Prize, a Pushcart Prize for Poetry, and a Washington State Arts Commission/Artist Trust Fellowship. Her work has been chosen for The Best American Poetry series by Billy Collins (2006) and Heather McHugh (2007) and was performed as part of the Vox series at the New York City Opera (2010). Recently she collaborated with the composer Dag Gabrielson and other New York musicians, filmmakers and dancers on a cross-discipline project titled 1,2,3. It was selected for showing at the American Dance Festival (International Screendance Festival) and had its premiere at Duke University on July 13th, 2013.

I enjoyed this wonderful essay. It is a little shocking to me how sung he was (prizes, grants, fellowships etc) and yet as time passed he is unsung enough that I had never heard of him. Thanks for the introduction.

Poets becoming ‘unsung’ is an interesting phenomenon to me. I think part of the reason that Francis is not better known is because he was a regional poet who didn’t have the ambition to be known beyond his region, unlike Frost.

How do poets become ;unsung’? I suspect mostly by the winnowing of time, which includes not being included in anthologies as time goes by. A while back, in correspondence with a well-published poet, I brought up James Dickey for a reason I can’t remember now, and the poet replied, “Who reads Dickey anymore?”

Look at the list of Pulitzer Prize winners in poetry. Not only are there the names I recognize, but who don’t seem to be read anymore (except perhaps by scholars and Ph.D. candidates), but the list includes names of poets I’ve never heard of, poets such as Leonora Speyer, George Dillon, Robert Hillyer, and Robert P. T. Coffin. Yet they apparently achieved substantial recognition in their time (assuming a Pulitzer Prize in poetry was taken seriously back in the 1920s and 30s).

P.S. When it comes to poetry, as in anything else, Americans tend to love ‘winners’ and dislike ‘losers’.

I have brought Francis’s poetry to a couple of what I will call Poetry Appreciation Classes in recent years and, to my surprise, his poetry was uniformly, nitpickingly dismissed as not being very ‘good’. The only speculation I have come up with for why this has happened is because the other participants had never heard of him, so therefore how can he be any good?

Of the American poetry anthologies I have looked at that would include poems from Francis’s prime writing era, I can only find the four poems of his that were included in “The Voice That Is Great Within Us.” My copy is from the eight printing in 1979. I don’t know if Francis has survived the editing of the most recent printing I am aware of, which is from 2001.

I’m interested in knowing of any other poetry anthologies in which Francis has been included.

Robert Francis is represented by one poem in The Penguin Anthology of Twentieth Century American Poetry, titled “Silent Poem.” I have suggested that Francis is a list-maker, and this poem takes that propensity to an extreme. If someone reading this poem were inspired by it to search out other Francis poems, that person may very well be disappointed if they were expecting something as experimental-seeming as this poem. (Since I don’t think the WordPress site supports multiple spacing between words, I have used ellipses to indicate how the words are spaced. There are no ellipses in the original.)

Silent Poem

backroad . . .leafmold . . . stonewall . . . chipmunk

underbrush . . . grapevine . . . woodchuck . . . shadblow

woodsmoke . . . cowbarn . . . honeysuckle . . . woodpile

sawhorse . . . bucksaw . . . outhouse . . . wellsweep

backdoor . . . flagpole . . . bulkhead . . . buttermilk

candlestick . . . ragrug . . . firedog . . . brownbread

hilltop . . . outcrop . . . cowbell . . . buttercup

whetstone . . . thunderstorm . . . pitchfork . . . steeplebrush

gristmill . . . millstone . . . cornmeal . . . waterwheel

watercress . . . buckhweat . . . firefly . . . jewelweed

gravestone . . . groundpine . . . windbreak . . . bedrock

weathercock . . . snowfall . . . starlight . . . cockcrow

–Robert Francis

What makes the poem silent? There are no verbs, so no action in the usual sense. It’s not a traditional lyric, and it doesn’t tell a story in the usual sense. The poem doesn’t seem to be addressing the reader in any usual sense, so in that sense, it is ‘silent’.

Yet even without the element of a traditional narrative, the words somehow seem tied together by more than merely being in the same poem. All of the words are compound words of two or three syllables. There are a lot of internal rhymes or near rhymes, and there is repetition of parts of compound words from one compound word to another. Also, although I don’t know if these compound words are also found in British English or Canadian English, they seem to me to have a particular American quality about them.

I am also struck by the fact that Rita Dove chose this poem to represent Francis, rather than one of his many more traditional poems. I haven’t read the rest of the anthology, but it makes me wonder if there is a bias toward post-modernism, indeterminacy (per Marjorie Perloff), and the influence of L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E poetry, among other influences that have appeared in the last thirty years or so.

I do like this poem. I’m curious of others like it as well and, if so, what they may like about it.

I like this poem, too, and think of it as an ingredients list for concocting a Frostian landscape. Living as I do in New England, I see these words as “local” — not in an isolating way, but in drawing the outlines of a distinctive setting with a discrete history I know well. This is a poem about the passing of a particular past in a plausible place. Many of these objects remain, but our relationship to them has greatly altered over time. What I love most, however, is the embroidery of Anglo-Saxon vowel sounds bounded by such confluent consonants.

Steven, I agree with you. Re-reading a couple of the poems that Ms. Larios quotes in her essay, in which Francis describes his delight in words themselves, it’s clear that Francis is headed in the direction of “Silent Poem.” We find Francis declaring in his poem “Hogwash”:

What besides sports and flowers could you find

To praise better than the American language?

“Silent Poem” seems like the logical consequence of what Francis says in “Poppycock”:

Keep your damn poems

only give me the words

they are made of.

Good point about this being “the logical consequence.” It’s easy to imagine that Francis created for himself a cul-de-sac or dead end, conceptually speaking. “Throw together any grouping of related and resonant words and you have a poem,” skeptics might say. “Where’s the depth of discourse?”

I wish I had time today to respond to my own hypothetical question. For now, I’ll point out that speaking “Silent Poem” aloud (nice irony there) is a markedly different experience from reading it unvoiced.

It’s reductive to say, “Reading aloud is more musical,” but the action or movement of this poem (any poem?) is a matter of performance, which is to say a matter of careful selection: pronunciation, inflection, pacing, possibly even phrasing if you consider it as written in lines (is it?).

Are the silences between words akin to rests in music? Is Francis forcing us to listen more closely without the armature of syntax?

Food for thought…

As printed in the anthology, the poem consists of six two-line stanzas. There are what I estimate as three to four spaces between words in each line.

Thanks for this. He is a list-maker, isn’t he. A list is a form, a pattern, that has forward momentum without action, as you say, without verbs. Very pleased that this essay has elicited comments about form and an appreciation of the poems as poems.

I was browsing through my copy of Francis’s book of short essays, titled “The Satirical Rogue on Poetry,” and I came across the slightly longer than two-pages essay titled, “Silent Poetry.” This is worth reading in relation to his poem, “Silent Poem.” In my opinion, Francis shares some ideas of objectivity in poetry that are similar to those of the so-called ‘Objectivist’ poets, without being as ‘wordy’ as they can be.

I am going to try and quote several relevant passages from the essay without copying most of it:

The idea of silent poetry or silence in poetry used to puzzle as well as fascinate me. I wanted such poetry to exist but I couldn’t quite see how if by “silent” was meant “wordless” or “non-speaking.”

How is silence achieved? A very short poem, like a cry on a still night, makes the surrounding stillness more vivid by breaking it. A long poem may have somewhat the same quality if it seems to be made up of very short poems, that is, has a fragmentary character. Or if transitions and connections are omitted. …

A poem that presents an object or scene or situation without comment approaches the silence of painting or sculpture. … Ultimately silence in poetry depends on restraint and control. The more a poem has of either or both the more silent it is.

Like a silent person a silent poem stands aside. Stands aside from chatter and chance conversation. Stands aside from all shouting. Stands aside also from artiness and calculated effect which we call rhetoric. Stands aside even from song, for song is even less silent than speech, the singing voice sounding continuously, whereas the speaking voice is broken by innumerable minute silences. …

[end of excerpt]

However, I don’t think “Silent Poem” is free of rhetorical devices, since it has a significant amount of word repetition (parts of some compound words being the same as parts of other compound words) and a significant amount of internal rhyme and near-rhyme. But it does omit transitions.

After reading a passage from an online google book, “Private Fire: Robert Francis’s Ecopoetry and Prose,” by Matthew James Babcock, I have a better idea as to why Rita Dove included Francis’s “Silent Poem” as his sole entry in The Penguin Anthology of Twentieth Century American Poetry.

Babcock writes:

Historically [in terms of Francis’s published individual volumes of poetry that were not published posthumously], it sits as a kind of stone marker, or trail’s end–the poem he waited his whole life to write until he found it, resting there for him, in the dusk of his days. In various critiques, reviews, and other sundry publications, “Silent Poem” surfaces more frequently than any other piece as an example of Francis’s essential aesthetic and subject matter. …

snip

Staggering in its simplicity, arresting in its arrangement, impossible to ignore–“Silent Poem” produces as much silence in readers as it draws from nature to enact its composition. That direct and hypnotic transfer of silence from nature to reader may indeed be just the point. Robert Shaw calls “Silent Poem” a work of “daring minimalism and amazing purity,” an “unadorned inventory” that “evokes an entire landscape and the life led in it…” In seeking to understand “Silent Poem, ” Donald Hall perhaps comes closest in labeling it a work of art that takes readers “deep into pure meaning.” Hall writes, “Actually among the most backward-looking of poems ….it takes poetry back to that condition of quiet and wonder when sounds were first formed and linked to objects of the world, when every word was fresh and a poem.”

I would like to add one more example of a Francis poem that I believe attempts to metaphorically create the idea of a wordless (silent?) poem:

Glass

Words of a poem should be glass

But glass so simple-subtle its shape

Is nothing but the shape of what it holds.

A glass spun for itself is empty,

Brittle, at best Venetian trinket.

Embossed glass hides the poem or its absence.

Words should be looked through, should be windows.

The best word were invisible.

The poem is the thing the poet thinks.

If the impossible were not

And if the glass, only the glass,

Could be removed, the poem would remain.

–Robert Francis (from the volume, “The Orb Weaver”)

Thanks for the interesting article. I’ve been a fan of Robert Francis since I first encountered his poem, “Waxwings.”

I think there are similarities between Francis’s work and Frost’s, but differences too. I think Francis likes word-play more than Frost does. Francis is like a cross between Frost and Kay Ryan, with a little Richard Wilbur thrown in for good measure.

One instance of this can be seen by comparing Frost’s “Nothing Gold Can Stay,” with Francis’s poem “Gold,” which has such phrases in it as: “(fall within fall)” [speaking of leaves falling in autumn rain], and the sentence: “The luminous birds, goldfinches and orioles, / Were gone or going, leaving some of their gold / Behind in near-gold, off-gold, ultra-golden / Beeches, birches, maples, apples. …” As also is apparent by this last sentence, Francis is a list-maker, more so than Frost, or so it seems to me.

Robert Francis has also been honored by the establishment of the Juniper Prizes, established in his honor by the University of Massachusetts Press.

Brilliant essay, Julie! I envy your ability to write so fluidly about such a complex subject as a major poet’s life and legacy. I’m struck by the directions that Francis’s work had taken once he (largely) moved away from the type of scene-setting we associate with Frost’s lyrics. In your examples at least, the persona seems to have shifted–and with it the reader’s expectations of the poems–from a solitary figure confronting a natural landscape to a disembodied voice cavorting about a linguistic space. Both are fruitful approaches for Francis, but the latter abandons the useful pretense of a narrator who is also an observer of (if not a participant in) what we are meant to take as an actual lived experience. Frost might generalize and rhapsodize, but rarely without close connections to a specified reality (the seasonal workings of Northern New England, say, in “Nothing Gold Can Stay”). That definite environment is the necessary context. Without envisioning that place (or constructing it for ourselves from the given details and our own sensory memories), we cannot fully inhabit the majority of Frost’s poems. Francis’s later poems are not without context, but their realities are invented syllable by syllable, and there is little in the way of a defined space. Playful, yes, but also potentially off-putting to a reader expecting a kind of drama or (to borrow from the visual arts) a more or less fixed figure-ground relationship.

I have been thinking some more about the differences between Robert Frost and Robert Francis regarding their poetry.

Robert Frost often includes himself as a ‘character’ in his poems; Francis, not so often. Frost is often both objective and subjective–I think an example of this would be “Tree at My Window,” in which he describes a tree being tossed by the wind, and then describes the tree seeing him “taken and swept” while he slept. Frost concludes by saying that the tree’s ‘head’ is “so much concerned with outer, / Mine with inner weather.”

Francis is not as concerned with “inner weather” as is Frost. Is this less poetically ambitious than Frost? Francis is more concerned with the imaginative interpenetration of things rather than emotional states, concerned with how seemingly disparate things can turn out to be a lot like each other, one thing resembling another, such as in “Sheep” that Ms. Larios quotes above, in which sheep and rocks are observed to be surprisingly similar in some ways. Likewise in Francis’s poem “Gold,” the somewhat gold-hued birds share their goldish colors, as they migrate away, with some of the trees whose leaves become somewhat gold-hued in autumn.

Francis also likes to point out how things or motions that seem opposite are, in fact, combined in a larger whole, perhaps the whole of creation. He does this quite successfully in his poems about athletes, such as “Base Stealer” and “Swimmer.”

In “Base Stealer,” Francis describes how ‘opposites’ can be contained in one person, describing the base stealer as “Poised between going on and back, pulled / Both ways taut like a tightrope-walker, / Fingertips pointing the opposites…”. And in “Swimmer,” he describes how what can kill can also sustain:

Observe how he negotiates his way

With trust and the least violence, making

The stranger friend, the enemy ally.

The depth that could destroy gently supports him.

With water he defends himself from water.

Danger he leans on, rests in. The drowning sea

Is all he has between himself and drowning.

[end of excerpt]

This poetry may not be in some ways as ambitions as Frost’s poetry, but I think it is as profound, in an often more objective way.

[The Francis poems mentioned are from “The Orb Weaver,” Middletown, Ct., Wesleyan University Press, fourth printing 1967.]

Interesting comments, worth following up on. Thank you,

Good biographical details, and material I’ve not read elsewhere — scant as it is. Did you visit Robert Francis’s cabin and take those pictures? Much of it looks exactly like I’d expect it to, just by his writing alone: austere yet warm, and conducive, above all, to work.

I did my own in-depth look at Robert Francis recently, so if anyone is interested in seeing some of his lesser known poems, you can find it here:

http://alexsheremet.com/review-now-forgotten-poetry-robert-francis/