I recently saw the film adaptation of Disgrace, J.M. Coetzee’s 1999 Booker Prize winning novel. In the novel, David Lurie is a white college professor in post-apartheid South Africa who has an affair with one of his students, a girl named Melanie Issacs. Melanie files a complaint against Lurie and he is dismissed from his post. He travels to the country to live with his daughter, Lucy, a young woman trying make her way as a farmer. At the farm, Lurie and his daughter are attacked by three black South Africans, foregrounding the huge issues of race and land ownership and post-colonial Africa. Lucy steadfastly refuses to leave the farm, even though her attackers continue to roam nearby. David begins a healing process himself by helping to euthanize stray dogs in a make-shift animal clinic.

I recently saw the film adaptation of Disgrace, J.M. Coetzee’s 1999 Booker Prize winning novel. In the novel, David Lurie is a white college professor in post-apartheid South Africa who has an affair with one of his students, a girl named Melanie Issacs. Melanie files a complaint against Lurie and he is dismissed from his post. He travels to the country to live with his daughter, Lucy, a young woman trying make her way as a farmer. At the farm, Lurie and his daughter are attacked by three black South Africans, foregrounding the huge issues of race and land ownership and post-colonial Africa. Lucy steadfastly refuses to leave the farm, even though her attackers continue to roam nearby. David begins a healing process himself by helping to euthanize stray dogs in a make-shift animal clinic.

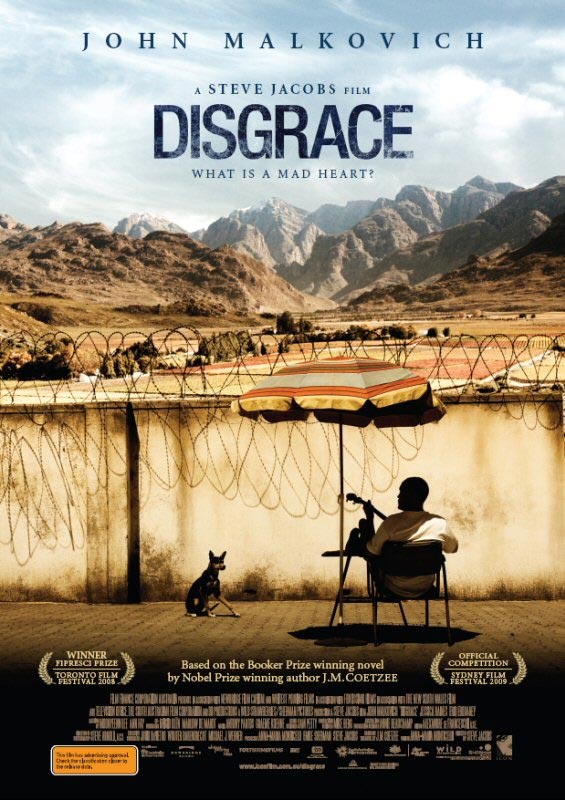

The book was sparse, dark and moving. I had very little hope that the movie could capture the tonality of the book. Overall, the movie adaptation managed to convey both the somber tone of the book and the meandering inner journey of Lurie. John Malkovich played Lurie, and though his quirky face (I mean that in a good way) at times had a comic effect, I thought his portrayal of this serious character was excellent.

I found myself thinking about Doug’s section on “Novel Form and Memory” from his book, The Enamoured Knight. Doug discusses how novels use “substitute memory devices,” usually within a character’s consciousness, to remind the reader of the what has happened and keep the novel from “sprawling.” By using only dialogue to access memory (or substitute devices), the story tends to get clunky and the dialogue begins to sound unnatural and un-dramatic.

I suspect this is the main reason feature films run mostly between an hour and two hours: films and plays simply can’t supply the substitute-memory devices needed to develop length (it has nothing to do with TV and shorter attention spans).

I read this quote a while back but it really stuck with me. I think this is the first time I’ve been able to apply this idea to a film adaptation of a novel I’m fairly familiar with. Longer scenes in the book became compressed in the movie. A novel of some 250 pages (I don’t have my copy…drat…I must have loaned it out…I’m a hoarder with my books too, so this causes me great pain.) probably takes me 6-8 hours of solid reading. So even in a good adaptation, like this one, so much of the richness and texture of the book gets lost.

—Richard Hartshorn

Rich, nice post. I kind of liked my little throwaway insight into the difference between films/plays and novels–glad you noticed.

Rich,

I love this book. I’ve probably reread it three or four times. The scene when Lucy and her father have visitors (I don’t want to give the drama away to anyone who hasn’t read it) is perhaps among the best scenes I’d ever read in fiction. The time is controlled so well, the terror matter-of-fact, and therefore all the more chilling. I had no idea they’d made a movie of the book. I am putting it on my Netflix list now.