In this passage the unnamed narrator is staying in Connemara in Galway County, Ireland. He rides a bicycle down to the seashore and reflects on death and the journey of Famine refugees across the ocean. His attention then turns to an outing in the same region with Gjini, an Albanian immigrant who acts as his occasional driver and tour guide. Gjini talks of his own experiences as a refugee. —Joseph Schreiber

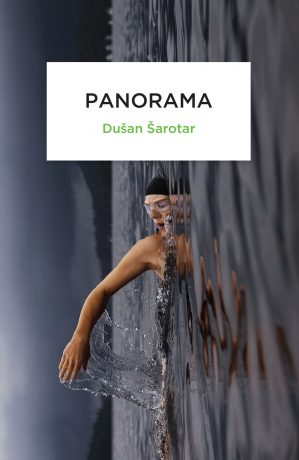

Panorama

Dušan Šarotar

Translated by Rawley Grau

Peter Owen World Series, 2016

208 pages, £9.99

.

Like a mirage at the end of the road, without reflection or gleam, dark and grey, a geometric plane shadowed in pencil on a yellowed sheet of drawing paper – that’s what the sea looked like – shallow, motionless, monastery beer spilled into eternity on to a black stone floor, but mainly trapped in a wide, ever wider, nearly limitless landscape; the nearer I was to the shore, the greater, the more impressive was the bay, in the middle of which stood a black lighthouse on sharp rocks, no bigger than a wizard’s ring, hovering on the motionless surface, while the master’s pale hand, still wearing it proudly, had long ago sunk beneath the sea. Without braking, I went down off the asphalt road on to a wide, neatly mowed grassy area in front of the boathouse and rode up to the sea. I leaned the bicycle against a low breakwater that was protecting the lawn from the high tide and slowly made my way over the grey sand, between the slippery rocks, the black pebbles and the rotting seaweed, into the oneness, the residue and abandonment, the world that remained when that sunken, dead arm last unclenched its hand and released the silt on which I now stepped, I thought as the smell washed over me, as if I was standing in an old, abandoned, invisible maritime cemetery, eerily beautiful none the less, like the romantic landscapes of the Old Masters. Death comes here to rest, the thought ran through me, after guiding the wandering, lost souls every day on their final journey, taking them far across the sea, to invisible islands chiselled from soft white light and overgrown with tall, dark silences, like a lyric nocturne in the middle of the sea; and after traversing the width and breadth of Europe, this is where she lays down her cold, sharp work tool, on this remote and hidden shore, and maybe for the first time in her eternal deathly life she lets slip from her shoulders the foggy shroud that shields her dark and hollow radiance, which pulses like a lighthouse from another world. Now I was hearing death with every cautious step I took in the black sand, sensing it in the swell, the gleam of the motionless waters, in every story, every marker along the road; I saw it on the threshold of every lonely deserted house standing open to the sky, roofless, without window or door, without a crucifix or the Book, which the fugitives

had taken with them, in good faith perhaps or in mortal terror, on their uncertain voyage across the sea that lay in front of me, and which, if not for ever lost or at the bottom of the sea, are now holy relics safely stored again in a drawer, in a new home across the Atlantic, as a memory of forebears, of a lineage with a forgotten name, and with a consciousness of ancestry, the dark trace of identity that still rings in the soul like a terrible wind in a dream; standing by the shore, I heard it, I saw it everywhere then – death, resting here. The scene, a stirring ritual of farewell, which apart from love is the single most deeply binding gesture that lies in a person’s heart (as the poet Boris A. Novak described it), was repeated, was literally doubled, as if I was hearing the echo of my inner voice, the first time I stood in front of the painting An Island Funeral, then on display at the Galway City Museum, which I visited one afternoon after my return to the city – but first I went with Gjini to the place he had told me about on the drive to Clifden, when we had first met.

A long, narrow road through a gorge, next to the dark, still shores of lakes encircled by mountain peaks, which I couldn’t distinguish from the great veiled white clouds, grey on the edges, that were gathering and rolling through the damp green vapours of the morning air and without accent or nuance in their description settling on

the muted orange wasteland, the damp and stifling, heavy, crumbling earth, which was hardly breathing, was gasping like tired, smoke-filled lungs, all this dripping damp and piles of mouldering, scorched grass lying on the earth were like a moist fuel, a black fire, burning earth – peat they call it here – which once warmed the walls of houses now a century deserted, which are scattered like lonely lost lambs across the entire country, bleating their harsh and gloomy, mysterious and mournful, but also beautiful and inaccessible, even cruel, Irish poem for human destiny, in an elusive tonality between the pathos of Gothic narrative and elemental folk balladry, or, maybe better, in the style of the romantic landscape painting that I was only now discovering here. That’s how I remember my first trip with the study group to this gloomy, hidden landscape, godforsaken you might say, which is how it seemed to me at the time. I remember that we stopped a few times on the way for no good reason, which from my student experience in my old homeland I found almost unthinkable; I mean that students would simply go trotting off when they had obligations or, worse, would forge friendships, be both drinking partners and academic colleagues, with the professors, Gjini said; so, as I said, whenever the sun came out for a moment and lit up the black surface of the lakes and the murmur of the mountain streams, we would run off far from the cars, away from the road, deep into the peatlands, hiding from the wind and the damp morning fog, which rolled down from the bare reddish peaks that wouldn’t be green for a while still, since winter had not yet breathed its last, and we would lie down between the tall, evenly cut, carefully stacked piles of black, decomposing earth, the peat, which was drying in the meagre sun. There, sheltered by earth, as if we were just now being born, we smoked cigarettes and drained bottles of black beer, and then moved on, a ragtag band of scholars, a brotherhood of professors and students. Although I was a foreigner, an immigrant, and still learning the jargon of high academia, and was moreover the oldest student in the group, a person who with some effort and for his own survival was merely skilfully concealing his homesickness, swallowing his anger, the disappointment and despair of the refugee, which were still mixed with will, with determination for a new beginning, and with inconsolable nostalgia, which, in fact, appeared and found its true name only later, when I had somehow got on my feet, as soon as I sensed that we would somehow make it, would be able to transplant ourselves, put down at least shallow roots in the new soil, and even later, when I would come back again and stop here, mostly on my own but occasionally with my family, and take long walks, when my second education, if you will, was successfully behind me (my first degree I had received long before in Tirana, in political science and journalism) – that’s when I realized we were in some way alike, we can’t hide or suppress our background, no matter where we are from or where we are born, we’re made out of a substance, like soil or an island, and on top of it, nostalgia, Gjini said, and the Irish understand this. I still grab every available moment I can to get in the car and escape here, to this magical, deserted, dark and inhospitable landscape, and for at least an hour or so I put on the mud boots I keep in the car and go for a walk over the damp ground, even when rain is pouring down on me or fog is hiding me; under its protection, in its sheer, shimmering whiteness, as if I was floating high above the waters, in the rediscovered memory of the landscape of my childhood, when I was similarly always getting lost in hollows and pastures, where no foreign word could reach me – my only world, our only world, was built solely of names, with no questions asked about meaning or significance – there, under the protection of silence and always the same faces, which accompanied me from my birth to my emigration and will in a sense be with me until I die, which I feel more and more each year, there I remembered and named things with a mere glance, I lived in an endless, silent and humble presence, there was nothing I missed or needed, and my whole reality, even the imagination in which I lived my childhood freedom, is still somewhere deep inside me, and from it, from this eternal source, I learn again every day unknown words, search for the deeper, the deceitful meaning of my second life, my immigrant life, Gjini said and was silent for a moment, as if he’d forgotten his point, or maybe we had missed a turn again, I thought. I didn’t see any sign or road marker, I said tentatively, and, in the awkwardness of the moment and just enough to let me wade through the silence, I started assiduously wiping the misted windscreen with my sleeve. When you are far from your language, you are also far from your home, more and more each day, and the distance increases and deepens with every new word; the lost word is usurped, seemingly replaced, by the other, more convincing, better word, which everyone can understand but which is still foreign; the immigrant, this eternal guardian but also suppresser of his own language, knows that the loss, the void, the dissolved malt of forgetting within it, which he tenaciously envelops and fills with learning, which is the only vaccine against loneliness, despair and madness, is nevertheless irreplaceable, painful and incurable, like love, Gjini said and noticeably slowed the speed at which we were driving. That’s why I come here, he said and looked off into the distance, to relearn the only language left from my childhood, the language of silence, of looking. I walk in silence and observe the landscape, the earth, I lose myself in the fog and soon I can’t make out anything any more; I don’t know who I am or even where I come from, I don’t even remember what language I’m thinking in, what language I name the world in. Then I write a poem. Totally wet, totally sweaty or totally cold, I drag myself back to the car and take a notebook out of the glove compartment,one that Jane gave me, and for a few minutes or until it gets dark, which is when, no matter what, I go home for supper since my family always expects me on the dot, so before I go home, I write. And I always try to translate every word, from one language to the other, so the poem from which I am made doesn’t burn up like earth, like black fire, peat, as they say here. At home, of course, we all speak Albanian around the table, not just my wife and older boy, but even our little girl, who was born here. Enough so she doesn’t forget where we come from, Gjini said and, taking a long bend in the road, he silently and with unusual concentration slowed the car, as if he was getting ready to make an important announcement; I could feel the tension and weight of his silence; then came a rumbling sound and a moment later the grey and weary road was flooded, the surface heaving with water; the storm, which came down into the gorge like an avalanche from the surrounding peaks, poured on to the road and the car was carried as if in the middle of a turbulent ocean. All I could see through the misted windscreen, which I was now wiping frantically with my sweater sleeve, were long translucent ribbons of water pouring down faster and faster, harder and harder from the low clouds, like a densely woven curtain; despite the gusting wind, which was constantly shifting the direction of the waves on the road, the heavy drops were falling to the earth in perfectly parallel lines, as in some ideal garden of pure Euclidean forms, and the very next moment, even before we had completed the bend in the road, even before I had made another desperate sweep of my arm to open a tiny slit for my eye, which searched for a view of the sky, as if seeking an answer or making a request – that’s when Gjini, with a curse on his lips and a curse in the corner of his eye, slammed on the brakes. There was pounding and popping, like stones hailing down on us, and when the roar of the rushing waters beneath the wheels had subsided a little, all we could do was gather our strength. Gjini, without a word of warning or any indication, hastily shoved open the door and I saw not a river but a turbulent sea racing past, and then this man, my guide, the only creature I knew in

the muted orange wasteland, the damp and stifling, heavy, crumbling earth, which was hardly breathing, was gasping like tired, smoke-filled lungs, all this dripping damp and piles of mouldering, scorched grass lying on the earth were like a moist fuel, a black fire, burning earth – peat they call it here – which once warmed the walls of houses now a century deserted, which are scattered like lonely lost lambs across the entire country, bleating their harsh and gloomy, mysterious and mournful, but also beautiful and inaccessible, even cruel, Irish poem for human destiny, in an elusive tonality between the pathos of Gothic narrative and elemental folk balladry, or, maybe better, in the style of the romantic landscape painting that I was only now discovering here. That’s how I remember my first trip with the study group to this gloomy, hidden landscape, godforsaken you might say, which is how it seemed to me at the time. I remember that we stopped a few times on the way for no good reason, which from my student experience in my old homeland I found almost unthinkable; I mean that students would simply go trotting off when they had obligations or, worse, would forge friendships, be both drinking partners and academic colleagues, with the professors, Gjini said; so, as I said, whenever the sun came out for a moment and lit up the black surface of the lakes and the murmur of the mountain streams, we would run off far from the cars, away from the road, deep into the peatlands, hiding from the wind and the damp morning fog, which rolled down from the bare reddish peaks that wouldn’t be green for a while still, since winter had not yet breathed its last, and we would lie down between the tall, evenly cut, carefully stacked piles of black, decomposing earth, the peat, which was drying in the meagre sun. There, sheltered by earth, as if we were just now being born, we smoked cigarettes and drained bottles of black beer, and then moved on, a ragtag band of scholars, a brotherhood of professors and students. Although I was a foreigner, an immigrant, and still learning the jargon of high academia, and was moreover the oldest student in the group, a person who with some effort and for his own survival was merely skilfully concealing his homesickness, swallowing his anger, the disappointment and despair of the refugee, which were still mixed with will, with determination for a new beginning, and with inconsolable nostalgia, which, in fact, appeared and found its true name only later, when I had somehow got on my feet, as soon as I sensed that we would somehow make it, would be able to transplant ourselves, put down at least shallow roots in the new soil, and even later, when I would come back again and stop here, mostly on my own but occasionally with my family, and take long walks, when my second education, if you will, was successfully behind me (my first degree I had received long before in Tirana, in political science and journalism) – that’s when I realized we were in some way alike, we can’t hide or suppress our background, no matter where we are from or where we are born, we’re made out of a substance, like soil or an island, and on top of it, nostalgia, Gjini said, and the Irish understand this. I still grab every available moment I can to get in the car and escape here, to this magical, deserted, dark and inhospitable landscape, and for at least an hour or so I put on the mud boots I keep in the car and go for a walk over the damp ground, even when rain is pouring down on me or fog is hiding me; under its protection, in its sheer, shimmering whiteness, as if I was floating high above the waters, in the rediscovered memory of the landscape of my childhood, when I was similarly always getting lost in hollows and pastures, where no foreign word could reach me – my only world, our only world, was built solely of names, with no questions asked about meaning or significance – there, under the protection of silence and always the same faces, which accompanied me from my birth to my emigration and will in a sense be with me until I die, which I feel more and more each year, there I remembered and named things with a mere glance, I lived in an endless, silent and humble presence, there was nothing I missed or needed, and my whole reality, even the imagination in which I lived my childhood freedom, is still somewhere deep inside me, and from it, from this eternal source, I learn again every day unknown words, search for the deeper, the deceitful meaning of my second life, my immigrant life, Gjini said and was silent for a moment, as if he’d forgotten his point, or maybe we had missed a turn again, I thought. I didn’t see any sign or road marker, I said tentatively, and, in the awkwardness of the moment and just enough to let me wade through the silence, I started assiduously wiping the misted windscreen with my sleeve. When you are far from your language, you are also far from your home, more and more each day, and the distance increases and deepens with every new word; the lost word is usurped, seemingly replaced, by the other, more convincing, better word, which everyone can understand but which is still foreign; the immigrant, this eternal guardian but also suppresser of his own language, knows that the loss, the void, the dissolved malt of forgetting within it, which he tenaciously envelops and fills with learning, which is the only vaccine against loneliness, despair and madness, is nevertheless irreplaceable, painful and incurable, like love, Gjini said and noticeably slowed the speed at which we were driving. That’s why I come here, he said and looked off into the distance, to relearn the only language left from my childhood, the language of silence, of looking. I walk in silence and observe the landscape, the earth, I lose myself in the fog and soon I can’t make out anything any more; I don’t know who I am or even where I come from, I don’t even remember what language I’m thinking in, what language I name the world in. Then I write a poem. Totally wet, totally sweaty or totally cold, I drag myself back to the car and take a notebook out of the glove compartment,one that Jane gave me, and for a few minutes or until it gets dark, which is when, no matter what, I go home for supper since my family always expects me on the dot, so before I go home, I write. And I always try to translate every word, from one language to the other, so the poem from which I am made doesn’t burn up like earth, like black fire, peat, as they say here. At home, of course, we all speak Albanian around the table, not just my wife and older boy, but even our little girl, who was born here. Enough so she doesn’t forget where we come from, Gjini said and, taking a long bend in the road, he silently and with unusual concentration slowed the car, as if he was getting ready to make an important announcement; I could feel the tension and weight of his silence; then came a rumbling sound and a moment later the grey and weary road was flooded, the surface heaving with water; the storm, which came down into the gorge like an avalanche from the surrounding peaks, poured on to the road and the car was carried as if in the middle of a turbulent ocean. All I could see through the misted windscreen, which I was now wiping frantically with my sweater sleeve, were long translucent ribbons of water pouring down faster and faster, harder and harder from the low clouds, like a densely woven curtain; despite the gusting wind, which was constantly shifting the direction of the waves on the road, the heavy drops were falling to the earth in perfectly parallel lines, as in some ideal garden of pure Euclidean forms, and the very next moment, even before we had completed the bend in the road, even before I had made another desperate sweep of my arm to open a tiny slit for my eye, which searched for a view of the sky, as if seeking an answer or making a request – that’s when Gjini, with a curse on his lips and a curse in the corner of his eye, slammed on the brakes. There was pounding and popping, like stones hailing down on us, and when the roar of the rushing waters beneath the wheels had subsided a little, all we could do was gather our strength. Gjini, without a word of warning or any indication, hastily shoved open the door and I saw not a river but a turbulent sea racing past, and then this man, my guide, the only creature I knew in

the middle of this deluge, stepped knee-high into the raging waters, in his shirtsleeves, with just a linen hat on his head, and vanished in the diagonal rain. His blurry shadow, which I tried to catch through the mist on the foggy windscreen, evaporated like a soul cut from its body, even before I could wipe the glass with my hand.

the middle of this deluge, stepped knee-high into the raging waters, in his shirtsleeves, with just a linen hat on his head, and vanished in the diagonal rain. His blurry shadow, which I tried to catch through the mist on the foggy windscreen, evaporated like a soul cut from its body, even before I could wipe the glass with my hand.

—Dušan Šarotar, translated by Rawley Grau

N5

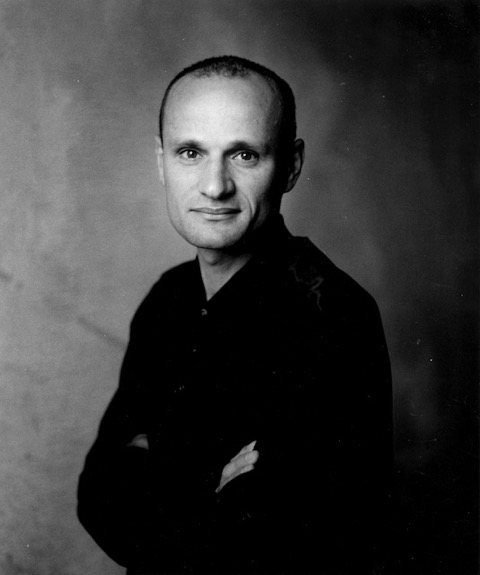

Dušan Šarotar is a Slovenian writer, poet, screenwriter and photographer. He has published five novels (Potapljanje na dah/ Island of the Dead, 1999, Nočitev z zajtrkom/Bed and Breakfast, 2003, Biljard v Dobrayu/Billiards at the Hotel Dobray, 2007, Ostani z mano, duša moja/ Stay with me, my dear, 2011 and Panorama, 2015), two collections of short stories (Mrtvi kot/ Blind Spot, 2002, and Nostalgia, 2010), three poetry collections (Občutek za veter/Feel for the Wind, 2004, Krajina v molu/ Landscape in Minor, 2006 and Hiša mojega sina/ The House of My Son, 2009) and book of essays (Ne morje ne zemlja/Not Sea Not Earth, 2012).

Rawley Grau holds a master’s degree in Slavic languages and literatures from the University of Toronto. His translations from Slovene include a book of essays by Aleš Debeljak (The Hidden Handshake: National Identity and Europe in the Post-Communist World, 2004), a collection of short stories by Boris Pintar (Family Parables, 2009), and a novel by Vlado Žabot (The Succubus, 2010).

.

.