x

“The same Society [of Loretto] will become, besides, an asylum or shelter for old age, decrepit or useless slaves, and whatever kind of sick or distressed fellow creature may call for their assistance, as far as this poor condition shall permit.” —Father Charles Nerinckx, 1813

“In America, we’re all immigrants. This land did not belong to the white people till we stole it.” —Ceciliana Skees, Sister of Loretto, 2016

For over two hundred years, the Sisters of Loretto have aspired to sanctify what history books have termed the dark and bloody ground of Kentucky into a home for the Virgin Mary. The first nuns, the daughters and sisters of pioneer farmers, envisioned the bluegrass plains and open skies to be as pure and untouched as the body of their beloved Mary. But the land they chose for the new home of God’s mother was as ancient as the hills of Jerusalem and as bloody as Golgotha. By 1812, when the original five Sisters of Loretto, Mary and Ann Rhodes, Ann and Sarah Havern, and Christina Stuart, began teaching Catholic children the rudiments of their faith, the land on which their motherhouse rested had been mapped, contested, divided, parceled, and sold, with generations of its original inhabitants besieged by epidemics and invasion. After over a century of warfare between natives, colonists, British, and French, the fields of central Kentucky were cluttered with detritus of battles primordial and fresh. The land was holy ground for many different people, but it was also blood land. In fact, the first Mother of the Sisters of Loretto, Ann Rhodes, purchased the land for the convent with the sale of a slave named Tom. This commodification of human flesh is a strangely disturbing beginning for an order of women who hoped to create an enclave for good works and education. How are we to understand women who swore vows of poverty but nevertheless bought and sold other Catholic souls? Such paradoxes of intentions run through the history of Loretto, as they do through the history of America.

Embedded deep into the consciousness of white settlers was the sense that the seemingly limitless fertile acres of America were an untouched Eden, the earth at its most new, its most pure. Perhaps the Sisters rejoiced that they were building Mary’s home in a newly born world, exempted from the sins of their forebears. But they also confronted a land of ruins, of mounds full of bones and the spirits that had once animated them. They were of a vocation and a religion that believed it was possible to converse with heaven, to hear the call of saints and spirits. If there were ghosts in the bluegrass, surely they glimpsed them. What did Mary and Ann Rhodes think when they discovered clay shards and copper medallions while digging in their gardens? How did they respond to the risings and ridges of the earth, the palimpsest of a land that had once teamed with people? I wonder if the nuns had a sense of the age of the land they inhabited, if they tried to fit the relics they found into their story of the creation and redemption of the world.

Loretto itself is named for Loreto, Italy, where pilgrims since at least the later middle ages have venerated a one-roomed stone house as the childhood home of Mary in Galilee. Tradition holds that angels carried the home to Italy to escape the ravages of the invading Turks. The choice of name is telling. The first Sisters hoped to recreate an ancient Judaean dwelling-place on the American frontier. None of them had ever been to Italy, so the Loretto they envisioned must have sprung from sermons, gospel verses, and their own imaginations—a home built of sandstone and flavored with olive oil, a place of simple domesticity where a young girl learned and grew into worthiness and first heard the voice of an angel. This home of Mary’s girlhood represented their hopes for themselves, for the children they would raise and send out into the world, and for those who would join them in their eternal prayers at the foot of the cross.

Loretto Motherhouse, Nerinx, Ky.

Loretto Motherhouse, Nerinx, Ky.

Yet other people possessed competing spiritual ties to the same fertile floodplains of the Ohio River Valley. The Shawnee believed that the central Ohio Valley was the heart of the world, given to them by Meteelemelakwe their Creator for perpetual sustenance. In recorded origin stories, Meteelemelakwe had lowered the ancestors of the Shawnee to the island of the earth in a basket and instructed them to travel to the river that would be their home for eternity. To them, the land that included Kentucky could never be sold, promised, or bargained away. Since the 1750s, they had fought a series of wars with the British and the Iroquois in order to keep settlers, hunters, and land speculators from encroaching further west. The Five Nations of the Iroquois, as well as the Cherokee, had twice sold the land to speculators, and in the Treaty of Paris in 1763, the British had ceded it away to the newly formed American government. Despite promises and bargains, the British did not stop the onslaught of eager settlers who traveled on flatboats down the Ohio River or climbed over the mountains through the Cumberland Gap to reach Kentucky. In 1775, there were only about 150 Anglo-Americans. By 1800, there were 220,855. Within ten years the number had doubled to 406,459.

The original Sisters of Loretto may not have been aware of the intricacies of failed treaties and false sales with the Shawnee that precipitated their arrival at Loretto, but they were certainly aware they were not the first inhabitants of their Edenic possession. White settlers had only been present in Kentucky for thirty-seven years, and those years had been rife with blood and conflict. The War for Independence lasted for eight years, but in Kentucky it had turned into twenty. Thousands of people, Shawnee, Lenape, Ohio Iroquois, French, and British, had been killed, taken captive, or died of starvation. The Sisters knew that only thirty years before, other settlers had crowded into forts for protection. They would no doubt have heard the tales that circulated among colonists of women taken captive, disappeared into the dark wilderness. In 1780, only five years before the Rhodes family emigrated to Kentucky, over 700 Shawnee and other warriors, along with British rangers, attacked several forts and captured 300 colonists. The experiences of the captives varied widely, with many, especially women and children, adopted into native families to replace lost members. Many were so pleased with their new lives they had no desire to leave when given the opportunity. But colonists considered the natives akin to demons, and many women feared the threat of sexual assault, true or not. The Old Testament books that made up the bulk of their readings were replete with battles, carnage, and violation. When the Sisters read of the rapes of Dinah and Tamar, did they envision Levantine kingdoms of centuries past or the forts and newly built farms of Kentucky?

It is difficult to get a sense of individual consciousness from the first five sisters—Mary and Ann Rhodes, Ann and Sarah Havern, and Christina Stuart. Any surviving key to their individual personalities has become shrouded in hagiography. According to the legend of Loretto, Mary Rhodes was so disturbed by the lack of schools in Kentucky that she began teaching her nieces and nephews in her brother’s house. She soon banded together with two other single ladies, Christina Stuart and Ann Havern, and the three of them moved into two old log cabins across the creek from Mary’s brother’s farm and invited local children to board with them and learn their letters. After a few months they revealed their joint desire to take the veil and sought the approval of their delighted priest, Father Charles Nerinckx, a Belgian immigrant who was hoping to nurture just such fledgling female communities. On April 12, 1812, the women traveled to the Nerinckx’s home on nearby Hardin’s creek. Kneeling outside the roughhewn church with a statue of Mary imported from Belgium, they received his blessing and he pronounced them the first sisters of the Little Society of the Friends of Mary at the Foot of the Cross. They were soon joined by Ann’s younger sister Sarah and Mary’s younger sister Ann.

According to the early histories of Loretto, the first Sisters were hardworking, courageous, devoted to their students and the survival of their Order. They faced hardship with tenacity and never wavered in their faithfulness to the Virgin Mary. In both their prayers and their actions, they strove to imitate her compassion for the world as well as the suffering of her son. And there is little to contradict or augment that portrait, as only a handful of documents from their own hands exist, and none of those are letters, diaries, confessions, or any of the narratives that indicate character or temperament.

Of course, some of this reverential biography must be true—in order to survive in unfamiliar country without stores and roads, living in split-log cabins, anyone would have had to be courageous and not averse to hard work. One of the original cabins still exists at the Loretto Motherhouse, although it’s been deconstructed and reconstructed several times. A tiny one-room cabin, with wooden shutters blocking most of the natural light, it manages to be at once claustrophobic and cavernous, the testament of an extremely harsh life for the people who crowded into similar such rooms. The rain and snow soaked in through cracks in the walls and the damp rose from the earthen floors. Ann Rhodes died of tuberculosis in a cabin like that. The Sisters and their students crowded into spaces impossibly small and uncomfortable to modern sensibilities. Somehow they managed—folding up the beds during the day to make room for meals and lessons, cooking outside in a lean-to, planting and canning vegetables to get through the winter. All that was true. But they didn’t have to do it alone. And they were hardly as impoverished as the stories would indicate. While the pioneer Sisters defied the elements and renounced all their earthly possessions for the greater treasures of Heaven, they still retained ownership of other humans.

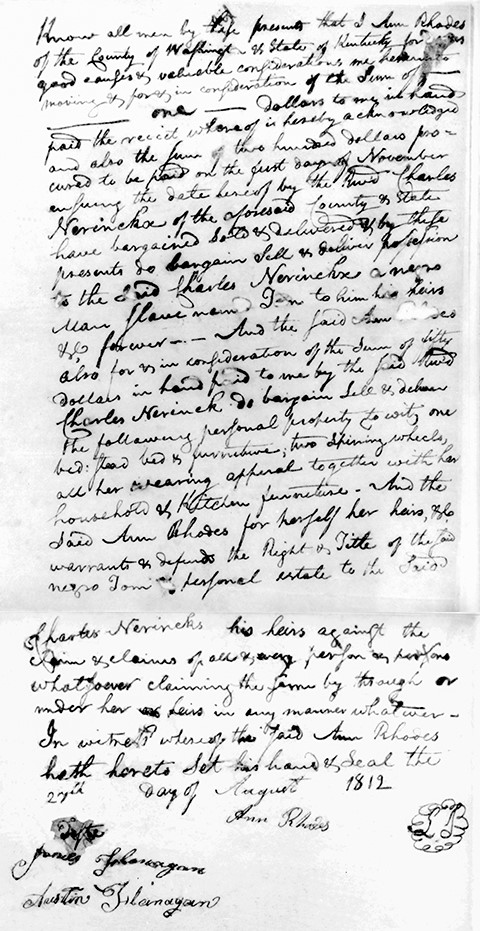

The first document to survive from the sisters is a record of purchase. In that loopy cursive of centuries past, Ann Rhodes recorded that she was selling one bed, two spinning wheels, assorted kitchen furniture, and one negro male named Tom to Father Charles Nerinckx in perpetuity for seventy-five dollars. She used the money to purchase the surrounding land, as well as to pay for repairs on the cabins. Father Nerinckx returned both Tom and the furniture to his spiritual charges and nothing more is written of him in the records.

Bill of sale for Tom and assorted household goods (used with permission of the Loretto Archives)

Bill of sale for Tom and assorted household goods (used with permission of the Loretto Archives)

Tom would be joined by others within a few years. Within the lifetime of Father Nerinckx (who died in 1824), there were enough slaves to merit two separate kitchens. An early set of copybooks from one of the Sisters recorded that Father Nerinckx had ordered that strangers were not permitted in either the white or the colored kitchens. In 1860, there were 70 slaves at the Motherhouse. In March of 1853, upon the death of Mary Rhodes, there were altogether 170 Sisters living at the Motherhouse and eight other schools and convents in Kentucky, Missouri, Kansas, and New Mexico. Since the other convents were smaller, there may have been as many slaves as Sisters at the Motherhouse.

The presence of those 70-some slaves places the stark purity of Loretto’s early mythos in further context. The brief references to Tom add another story, of more than 70 other stories stitched into and around the central narrative of early Loretto. But those stories are shadows, lost on the edges of old diaries, fallen in between the ripped creases in letters. We know the occasional name, the occasional number, but we don’t have any written memories relating what life was like for those who lived, worked, prayed, and died in the service of the Sisters at the Motherhouse.

Everything is conjecture, based on comparisons and built around blank spaces. But Loretto rose from two cabins in 1812 to a sprawling estate that was both a school, a house of worship, and a fully functioning self-sustaining farm community, and slaves were responsible for much of that achievement. Their labor also contributed to the flourishing of the larger Catholic community in Kentucky—owning slaves gave the Sisters the free hours to teach Catholic children, which was their central goal. They could not have fulfilled their mission without slaves to till their grounds and tend to their laundry, harvest their corn crop, milk the cows, and see to the never-ending labor of an extensive farm.

The Sisters of Loretto bought and sold slaves, and some received them as inheritances from family members. According to her father’s will, Mary Rhodes received “a boy named George, a girl named Anna, and one feather bed and other furniture.” New postulants also brought slaves along when they joined, as part of their dowries to the institution, such as the four women who joined in 1817, bringing ten slaves with them. Many of their transactions’ records were destroyed in a fire, but at the neighboring Sisters of Charity, a convent of similar size, an entry for the annals in 1840 records that “they bought five negro men; two women, two girls and two boys . . . . The prices of hire were also very high; and the Council decided it was better to buy servants for the farm etc., then pay so much for hire and often get bad ones.” In the same year, Catherine Spaulding, the foundress of the Charity convent, sent money back to the Sisters for the purchase of two girls. She was the same woman who had declared that, “our Community must be the center from which all our good works must emanate.”

One of the hallmarks of slave experiences was a marriage of Christian religion with native African practices, memory, and experience merged into a distinctly African-American creation. This was true regardless of denomination. How do we understand the lived moments of spirituality for individuals enslaved in a religious house? Throughout Kentucky, masters and slaves worshipped in the same churches, with slaves in the back or up on a balcony. Father Nerinckx had insisted that the slaves in his parishes, which included Loretto, receive the sacraments so if they believed in the teachings of the church they served, they knew their souls belonged only to God. They were washed with the same water at birth and departed their bodies to the same rites. Regardless of whether slaves accepted their status or rebelled in their hearts, they participated in the rituals of their masters. And judging by the numbers of African-Americans who remained Catholic after emancipation, they imbibed the meaning of those rituals. African-American Catholics didn’t split off into their own congregations, unlike Protestants who formed specifically black denominations, historically spoken of as the Black Church. Catholics insisted on communion within the larger body of Christ.

Living as a slave in a house of education may have provided opportunities, even if only grasped in stolen moments. Another scribbled statement, from Father Nerinckx, copied in a notebook by an anonymous hand: “Permission is given for the sisters to instruct colored women and girls, but they may not converse with them without the superior’s permission, and the superior should be vigilant that no disorder occur through her negligence.” Unlike other states, it was never illegal to teach slaves to read and write in Kentucky.

Given that some slaves in Loretto were literate, it’s hard not to wonder what they may have read and how their reading affected their identities. It’s tempting to imagine slaves at Loretto developing subversive ideas through books. Abolitionist literature existed in Kentucky, and it’s not impossible (although impossible to prove) that some of it made its way into the kitchens, laundry, and slave quarters of Loretto. Beginning in 1822, the Kentucky Abolition Society regularly published a newspaper, and of course, Uncle Tom’s Cabin had sold 300,000 copies the first year of its publication. Even if none of these works ever reached the confines of Loretto, however. there was no shortage of bibles, and biblical stories, with tales of Israelites yearning to be free from bondage and the Lord hearing their prayers, were among the most subversive in a slave-holding society. The religion of the Sisters preached equality before God, equality among the members of the body of Christ, however they may have practiced it. And slaves and Sisters alike must have recognized this contradiction. If black women were the ones more likely to be literate, as Nerinckx’s memo suggests, than the spiritual hypocrisy they faced was even more baffling. The lessons they learned in the bible as well as those they received during the liturgy directly contradicted social dictates about the worth of both their souls and their bodies.

The female slaves occupied a strange space at Loretto. According to historian Deborah Gray White, in popular imagination, the black female body was oversexed, as ripe for exploitation as it was devoid of virtue. The same society that prized white female chastity valued black women as objects of male lust and as breeding sows to provide more property. Owners had no stake in preserving black virginity. At a convent, the contrast between the different conceptions of womanhood could hardly have been more starkly apparent. The nuns possessed the privilege of control. In the days before effective birth control, monastic vows offered women a socially approved alternative to dangerous and potentially tragic cycles of pregnancy, childbirth, nursing, and childrearing. Vowed women controlled their bodies, tempering them with fasting and long hours of prayer, but never ceding physical or legal control to a man.

Black female slaves, however, were not the owners of their own bodies. They could hardly make decisions about their virtue when they could be married off and sold away at another’s whim. In 1837, at the neighboring Sisters of Charity, the Sisters, “resolved that the black girl Matilda be sold for $550 to a catholic who will not send her down River.” “Down River” referred to the Mississippi River, the main conduit into the deep South. Slaves sold down the river faced separation from their families as well as increasingly brutal labor conditions on cotton plantations.

Female slaves also faced sexual violence from white men and black slaves alike. And yet the female slaves at Loretto found themselves serving other women whose flesh had been demarcated as not only privileged, but sacred. A young black woman could wonder, surveying the untouched bodies of her communal mistresses, am I not a virgin too? And yet that virginity was somehow a less perfect offering for the God whose waters had baptized them both.

§

Loretto was meant to be the home of the Virgin Mary, but Kentucky is not Nazareth, and its landscape bears the scars of its twinned worlds. A biography of Mary’s sorrows, rendered in marble, lines the path to the cemetery at the Motherhouse. The Dolors of Mary, as they are known, trace the holy family from the flight into Egypt through the tortured steps of the Passion. Artistic tradition limits the sculptures to seven, but each tangle of stone limbs bespeaks a lifetime of maternal care, from the loss of her child in the Temple at Jerusalem to her final harrowing witness. At the fourth station, Mary meets Jesus in the streets as he carries the cross on his back. They lean into each other in an embrace, the sun and the wind driving against them, the temple as their sky. She helps him bear the cross just for a moment but knows she must relinquish him to his fate and its weight.

If you follow the path of the Dolors to the end, you find yourself at a rough stone slab about the height of a tall person that rises above the gravestones of deceased Sisters, a memorial decorated with a handsome brass plaque featuring a relief row of African-featured profiles—women in headscarves, an old man with a worn expression, a young child with round cheeks. It has stood there since 2000, bearing all the known names of the slaves at Loretto, names gleaned from archives, from contracts, handwritten in faded ink, slanted antiquated handwriting, catalogued in acid-free boxes numbered on shelves in the archives. Clearly the names listed on the stone are just fragments of memories, brief references in bills of sale— “Aunt Gracy, Aunt Bell, The Drury Family of Ten slaves, Anna and George, the slaves inherited in 1838 by Sister Laurentia Buckman . . . And all those whose names have been forgotten.”

The placement of the Dolors and the memorial stone together perfectly encapsulates the paradox of slavery at Loretto. The Sisters of Loretto sorrowed with Mary and suffered with Jesus. That moment existed eternally and defined their entire identity, including their prayer life and their earthly mission. To that end, they created their own forms of suffering to emphasize with Jesus—asceticism in food, sleep, dress, separation from friends and relatives, and obedience to the rule and will of superiors. But who embodied sorrow and suffering more than their slaves? Tom, Aunt Gracy, Aunt Bell, and all the other men and women of Loretto enacted the torments of the Cross on a daily basis, with their forced labors and subjugated wills. In the reminders of their inferiority, whether in the form of cruel taunts, harsh censure, or gentle explanation, they lived out the experiences of Jesus, tormented and insulted on the road to Calvary. And they bore a Cross from the moment of birth. One African-American spiritual, with clear Catholic overtones, equates the affliction of slavery—the hollering and scolding of masters—with the burden of the Cross.

I want some valiant soldier here … To help me bear de cross

Done wid driber’s dribin’ …

Done wid massa’s hollerin’ …

Done wid missus’ scoldin’ …

I want some valiant soldier here … To help me bear de cross

O hail, Mary, hail! O hail, Mary, hail! O hail, Mary hail!

To help me bear de cross.

The sufferer cries out to Mary, who, in Catholic literature and liturgy, is the archetype of sorrow. How many sorrowing mothers watched their children sold away from them? Watched the children left to them broken in body, in the fields, at the whipping post? While the Sisters sorrowed with Mary, did the slaves hope that Mary sorrowed with them?

§

Loretto came of age alongside the state of Kentucky and indeed, the entire United States, so to get lost in its grounds and to dig through the extensive archives is to confront the paradox of American history. And when we study that history, when we read the names on memorial stones or dig into the sinews of the earth, we learn that we are a species of dark hearts and infinite cruelties, with conflict woven in our souls. We also long for salvation, whoever we are, and have composed an infinite variety of paths back to the sky or into the ground, myths of suffering and redemption, and stories of sin and forgiveness. Our first hope for atonement, for the bodies broken and displaced on a multitude of crosses, for the voices disappeared and the records lost, is acknowledgment. And once we have built the memorial stones and reached the ends of the records, what then?

Many thanks to the Sisters of Loretto and their co-members, especially Eleanor Craig, Susan Classen, Antionette Doyle, and Ceciliana Skees, for their candor and their generosity.

— Laura Michele Diener

x

Works Consulted

Barnes, Mary Matilda SL. One Hundred and Fifty Years. Loretto Motherhouse Archives, Nerinx, KY.

Boles, John B. Religion in Antebellum Kentucky. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1976. Print.

Butler, Anne M. Across God’s Frontiers: Catholic Sisters in the American West, 1850-1920. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012.

Campbell, Joan SL. Loretto: A Early American Congregation in the Antebellum South. St. Louis: Bluebird Publishing, 2015. Print.

Joan Chittester, Ed. Climb along the Cutting Edge: An Analysis of Change in Religious Life. New York: Paulist Press, 1977. Print.

Copeland, M. Shawn, Ed. Uncommon Faithfulness: The Black Catholic Experience. Maryknoll, New York: Orbis Books, 2009.

Gollar, C. “Catholic slaves and the slaveholders in Kentucky.” Catholic Historical Review [serial online]. January 1998;84 (1 ):42. Available from: Academic Search Premier, Ipswich, MA. Accessed February 8, 2016.

Harrison, Lowell R. and Clotter, James C, Eds. A New History of Kentucky. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1997.

Hogan, Margaret A. Sister Servants: Catholic Women Religious in Antebellum Kentucky. Diss, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2008.

I Am the Way, Constitutions of the Sisters of Loretto at the Foot of the Cross. Nerinx, KY, 1997. Print.

Lakomäki, Sami. Gathering Together: The Shawnee People through Diaspora and Nationhood, 1600-1870. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014. Print.

Lewis, R. Barry, Ed. Kentucky Archaeology. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1996. Print.

The Loretto Community. A Century of Change: 1912-2012, Loretto’s Second Century. Point Reyes Station, CA: Chardon Press, 2012. Print.

Suenens, Leo Joseph, Card., The Nun in the World: Religion and the Apostolate. Westminster, MI: Newman Press, 1963. Print.

White, Deborah Gray. Ar’n’t I a Woman?: Female Slaves in the Plantation South. London: W.W. Norton and Company, 1985. Print.

Laura Michele Diener teaches medieval history and women’s studies at Marshall University in Huntington, West Virginia. She received her PhD in history from The Ohio State University and has studied at Vassar College, Newnham College, Cambridge, and most recently, Vermont College of Fine Arts. Her creative writing has appeared in The Catholic Worker, Lake Effect, Appalachian Heritage, and Cargo Literary Magazine, and she is a regular contributor to Yes! Magazine.

x

I am quite late but glad to have found this essay. Last February, I visited these grounds for the first time when my sister and I spent a weekend on silent retreat with the Sisters at Loretto Motherhouse. Reading this, Laura, I realize how little I knew about the convent and its history, and I look forward to exploring with open eyes.