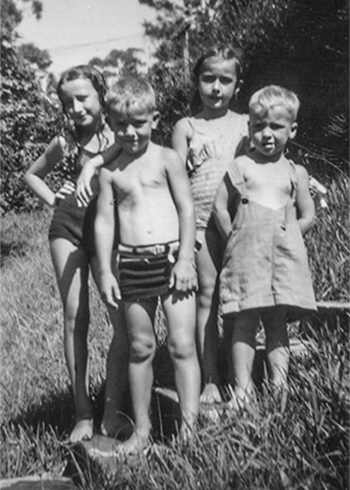

With Uncle Henry’s boys at The Knoll, c.1950

With Uncle Henry’s boys at The Knoll, c.1950

x

‘Wind it up again,’ I say to my big sister, and she rapidly turns the silver handle of Auntie Essie’s wind-up gramophone. It’s set in the top of a beautiful wooden cabinet. The doors beneath swing back to reveal shelves of records, glossy black seventy-eights in their thin brown paper sleeves, each with its round cut-out peephole through which I can see the record label and the little dog listening to his master’s voice.

The black lacquered cabinet is almost taller than I am. When I push up the lid it clicks open. I can just see the turntable, covered with green baize, and the twisting silver arm with its round head, and the glittering needles higgledy-piggledy in the container like an egg cup, set in beside the on/off lever. ‘Now change that needle often,’ Auntie Essie says, ‘or you’ll ruin those records.’ She’s not happy that we’re playing with the gramophone in the big lounge room with its elegant arm chairs and those large round Jap-silk cushions of scarlet and midnight blue. I expect she wasn’t allowed in there when she was growing up. But my Uncle Henry said, ‘Of course they can play in there. It isn’t a morgue!’

The deep groaning voice emerging from the cabinet gradually rises in pitch as my sister turns the handle until it’s Nellie Melba singing ‘One Fine Day’ in a shrill reedy voice. But soon she slows again to a drunken drawl. My sister cranks it up once more and Nellie soars to greater heights. But sometimes it isn’t Nellie; it’s that man called Gigli or the other one called Caruso. They sing sad songs from far away, amongst all that crackling. The labels say things like ‘Nessun Dorma’ and ‘Turandot’ but that’s some foreign language.

There are heaps more records. My mother says they’re mostly popular songs and dance music from the 1920s and 30s when Auntie Essie and all her brothers were growing up. There’s one dance called ‘Black Bottom’. I think that sounds a bit rude. And there are Charlestons, which I love, and Foxtrots and Two Steps, whatever they are. My favourite record, apart from ‘One Fine Day’, is a song I like to sing:

‘My dog loves your dog,

And your dog loves my dog.

Both our doggies love each other

Why can’t we?’

.

Ethel

Auntie Essie lives with Grandfather at The Knoll. It stands on top of the hill overlooking the lake at 99 The Esplanade, Speers Point. We have to go there for holidays. The gloomy house is where my father grew up with Essie and his four brothers: my Uncle Art, Uncle Henry, Uncle Aub and Uncle Griff. They call Essie ‘Sis’ but her real name’s Ethel.

Essie on the right beside my father and me. My sister seated by Grandfather, Uncle Aub and the Vauxhall Tourer, c.1951

Essie on the right beside my father and me. My sister seated by Grandfather, Uncle Aub and the Vauxhall Tourer, c.1951

Auntie Essie sits in the back room on the hard brown armchair by the wireless, listening to the serials. She turns the volume up high because she’s a bit deaf although she’s the same age as my mother and that’s not old. Her favourite serial’s called ‘When a Girl Marries’. At other times she sits reading love stories about doctors and nurses from the English Woman’s Weekly, and she’s always smoking those Capstan cigarettes. My mother doesn’t smoke or hardly ever (only when her friend Daisy comes to stay) and she doesn’t read love stories in magazines. She reads books.

Essie’s fingers are stained yellow and so are her big front teeth. My mother says it’s from the nicotine. She has permed yellow hair but I don’t think that’s the nicotine. She wears sensible lace-up shoes because she’s a nurse and sensible clothes and hats when she goes out.

It’s always dark and musty at The Knoll and there’s the smell of dank seaweed from the lake, moth balls from the cupboards and that cigarette smoke, mixed with perfumes: lantana growing wild up the gully, and frangipani blossoms floating in the black lacquered bowl on the traymobile in the dining room.

Essie doesn’t swim in the lake although it’s just down the bottom of the steep driveway. I’ve never seen her in a swimming costume—but we often go down to the lake with our mother and sometimes with our father when he doesn’t have to be back home, doing the mine inspections. Mother looks glamorous in her home-made floral swimming costume and her wide black hat. We have to wade out through that slimy black sea grass. It’s like thousands of black spiders under water waving their legs.

At the lake with my father, c.1953

At the lake with my father, c.1953

My mother thinks it’s a nightmare having to stay at The Knoll for a fortnight. ‘Now mind your Ps and Qs,’ she says to us because Auntie Essie’s a stickler for manners, so we always have to be minding them, especially at the dinner table. You have to know how to use the butter knife and where to put the salt when you’ve fished it out of the little cut-glass salt cellar with the tiny silver salt spoon. You’re not to sprinkle it over the food like Uncle Aub does. He taps the little spoon with his fork and the salt goes everywhere. My mother says this makes Auntie Essie go apoplectic.

On Mondays Essie cooks liver and bacon, Tuesdays it’s tripe in white sauce, Wednesdays it’s sausages and gravy, Thursdays steak and onions—and it’s always a roast on Sundays. She keeps the chocolate biscuits in a big old Bushell’s Coffee jar locked in the kitchen cupboard, and the starched tablecloths and serviettes and the silver serviette rings and the cruet set locked in the sideboard, and the sheets and towels locked in the press outside the bathroom, and her clothes locked in the black lacquered wardrobe in her bedroom. She has all the keys on a large wire ring in her apron pocket. They jangle when she pulls them out.

I know her wardrobe’s full of long satin and shot-silk evening dresses and old silver and gold evening shoes and a fox-fur like my mother’s only the fox still has its head and it has glass eyes. I don’t think Auntie Essie goes to balls any more but she’s quite slim when she’s wearing her corset. My mother says it’s just a pity Essie’s been left on the shelf, looking after Grandfather, but she’s a very good aunt because she remembers birthdays and Christmas. Every year she sends me another pair of frilly shortie pyjamas in flamingo-pink nylon.

.

Mrs Whitter

Mrs Whitter is the cleaner. She’s been cleaning The Knoll since Auntie Essie was a girl. She always did the washing, and ran the Ewbank Carpet Sweeper over the hall runners and the Oriental carpets in the lounge room, the bedrooms and the dining room, and mopped the black lacquered wooden floors where they showed, and polished the silver with Silvo and the murky brown linoleum in the kitchen with Johnson’s Wax, on her hands and knees. Then she cooked the batch of bread before she went home.

She can’t get down on her hands and knees now because she’s old and fat with wispy white hair and a bristling wart on her chin and bunions sticking out of her feet. That’s why she slops round with the broom and the mop, and runs the old carpet sweeper over the threadbare hall runners in her carpet slippers. She doesn’t make the bread any more because the baker boy calls in his white apron. He walks all the way up the steep driveway with the bread in a wicker basket while the baker’s van waits down by the lake. Her grown-up daughter comes to help sometimes. She’s Mrs someone else and I don’t like her very much—but I like Mrs Whitter.

‘Come on love,’ Mrs Whitter says to me after she’s added more wood to the fire under the bricked-in copper and the water starts to boil, ‘You can help me sort these clothes.’ So I sort the whites from the coloureds, and she grates the Sunlight soap and plunges the sheets into the boiling froth and shoves them down with the copper stick. Then the laundry’s full of steam.

I help her with the wringer after she’s finished rinsing. The wringer’s what my mother calls a ‘mod con’—much smaller than the old mangle and it clips onto the edge of the concrete laundry tubs. After Mrs Whitter feeds the clothes between the rubber rollers, I ease them out the other side and drop them in the wicker clothes basket. She turns the handle and it’s hard work. ‘Not ’arf as ’ard as that mangle,’ she says.

I know about that mangle with its big wooden rollers and rusting iron frame. It’s sitting in the garage down the bottom of the drive beside the old wooden boat called ‘The Mary Jane’ that nobody takes out on the lake any more. When my Uncle Henry was a small boy he was watching his big brother (my Uncle Art) having fun with the mangle. ‘Put your finger in there,’ Art says, pointing to a small gap between the cogs. Little Henry pokes his finger in the hole; Art turns the handle and the end of Henry’s finger is chopped right off. And that’s why my Uncle Henry has only half an index finger on his right hand. They nearly turned him down when he went to join the Royal Australian Air Force during the war, because of that finger.

.

Grandfather

‘You on the air, Pop? The batteries flat?’ my father says. Grandfather doesn’t hear. He sits wheezing, glasses near the tip of his nose, tartan scarf tucked in, smelling of Vicks VapoRub. He fiddles with the gadget in his breast pocket, the plastic-coated wire twisting its way to his ear. He fumbles with the knob then leans forward expectantly, hand cupped behind the other ear. It’s hard making conversation. You have to yell. ‘Speak up!’ he says.

We’re used to yelling in our family. Quite a few people are hard of hearing including Auntie Essie and Great-Aunt Thursa. But my grandfather is the only one whose eardrums were shattered in that coal mine explosion in the Hunter Valley just after the Great War. He lost several fingers as well.

The closed-in end of The Knoll’s veranda by the magnolia tree is his office. He spends much of the day pouring over his maps, fine-nibbed mapping pen in hand, meticulously incising contour lines in Indian ink, filling spaces with vivid colours from small glass ink bottles. He carefully removes the cork and dips his brush in the ink, steadying the bottle with his thumb and the two remaining fingers of his other hand. The finished oversized geological maps are stored in the red cedar cabinet. ‘Can I see?’ I say again and he slides out a tray to reveal another wondrous work. ‘Just look,’ he says, ‘don’t touch!’—and my small fingers itch.

A glass specimen case covers the top of the cabinet. I’m not tall enough to see, so I drag over the delicately carved chair and stand on the sprung seat. I lean my forehead against the glass to gaze at the treasures: black and sparkling anthracite, rust-coloured ironstone, shale embedded with leaves or shells, gold-flecked quartz, glittering marcasite, round basalt river stone—and then there are the uncut gems. The labels, which I can’t yet read, are in Indian ink, the intricate work of a mapping pen.

From an overhanging branch of the giant magnolia (where the bandicoot and I met in the dark) hangs my grandfather’s old-fashioned swimming costume of grey-and-black-striped wool. It hangs by the shoulder straps to dry. In summer, despite the asthmatic breathing, he walks, shoulders back, down the hill to swim in the lake. He eases himself in from the end of the jetty beyond the black sea grass, strikes out overarm then changes to an easy sidestroke. Later, I see the swimming costume, once more dangling by its shoulder straps from the branch to dry.

We always hear him coming when he drives to our house, just up the hill from the mine. Old Bess, his ancient utility truck, sounds like a tractor. I can see the dust and blue smoke as she grinds her way up the hill on the rutted gravel track. She was bought to replace the old Hupmobile which, as my father said, guzzled up too much fuel, and petrol was still rationed. He’d been lucky to pick up another car; secondhand ones were scarce after the war and new ones unavailable.

Bess has to be cranked to get her going. First my father strains at the crank handle, then Uncle Aub or Uncle Art, but each time the engine dies and she has to be cranked up again. Grandfather sits in the car dressed in his old suit and hat, hopefully pumping the accelerator. Blue smoke emerges, not only from the rusty exhaust pipe but also from under the bonnet. When she finally roars into life, he bashes the dented door shut, grinds the gearstick into place and sets off with a shout and a wave, scattering chooks as he goes.

‘He’s a menace on the road!’ my father says. Grandfather drives slowly and carefully but, not having the gadget turned on, he doesn’t hear cars tooting impatiently from behind on the narrow roads, so he doesn’t move over to let them pass. This results in long queues like funeral processions.

§

Years later, as he painstakingly drove his Morris Minor towards home, my grandfather was rammed from behind by a semi-trailer—at least that’s what they concluded at the official inquiry. His car left the road, turning over as it headed down an embankment. The semitrailer didn’t stop and the driver was never apprehended. My grandfather spent his last years an invalid at The Knoll (that grand old house above the lake) with Ethel, my Auntie Essie—his maps now untouched in the cabinet, the pens in their case.

When I received news of his death in the early 1970s, I thought of him, long ago, sitting at his desk, glasses near the tip of his nose, smelling of Vicks VapoRub. I’m sitting beside him on a high stool: a small child drawing fairies with a mapping pen—meticulously colouring their wings with the fine brush I’ve dipped in jewel-coloured ink.

Me in the late 1980s, not long before The Knoll was sold

Me in the late 1980s, not long before The Knoll was sold

—Elizabeth Thomas

Elizabeth Thomas is an Australian writer, born before the end of World War II. She graduated from London University in 1970. Her first book, Vanished Land, was published in 2014 after she retired from the field of music and music education. Currently she contributes to Numéro Cinq and is working on short stories and a memoir.

x

x