With The Reactive, Ntshanga seems less interested in writing a novel with a straight, linear plot than he is in writing one about overarching themes of family, denial, and disparity. — Benjamin Woodard

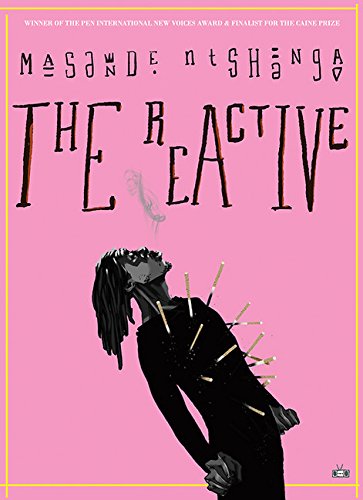

The Reactive

Masande Ntshanga

Two Dollar Radio

174 pages ($15.99)

ISBN 978-1-937512-43-9

Topping 6 million infections, South Africa is home to the largest number of HIV cases in the world, and it’s an understatement to say that the country’s government has paved a rocky road in its reluctant battle against the lentivirus. Though educational programs flourish today, as does a substantial antiretroviral (ARV) drug treatment program, ramifications from past decades linger. Without proper identification and care, infection numbers rose throughout the 1980s and 1990s, and the early 2000s saw high-ranking officials, particularly then president Thabo Mbeki, actively engaged in AIDS denialism, claiming tenuous links between HIV and AIDS and chastising aggressive medicinal assistance. During this time, ARVs were scarce, despite offers from international manufacturers to supply patients with inexpensive medication, and those who received such treatments were few and far between.

Masande Ntshanga’s engrossing debut novel, The Reactive, unfolds during the Mbeki presidency. It’s 2003, and Lindanathi, a young HIV infected man in Cape Town, spends his days huffing industrial glue with his friends Cecelia and Ruan. When they’re not slumming in an apartment, the trio work together to illegally sell Lindanathi’s extra ARV supply—Cecelia and Ruan are not infected, and Lindanathi is a lucky ARV recipient—to local reactives for quick cash. In lieu of chapters, the novel is broken into five parts, and the first dedicates itself to establishing the relationship between Lindanathi, or Nathi, and his friends, who casually float in and out of day jobs, HI Virus group meetings, parties, and cloudy conversations. Nathi tells his story in first-person POV, and the reader is swiftly immersed into the daily ennui of the gang. Two Dollar Radio, the novel’s American publisher, sells Ntshanga’s narrative on its website as “James Baldwin + Transpotting + Harmony Korine,” and the comparison is apt. More than once, I was reminded of the closing line of “Sonny’s Blues”—“For me, then, as they began to play again, it glowed and shook above my brother’s head like the very cup of trembling”—while reading. Like the Biblical cup of suffering tenuously hovering over Baldwin’s character, waiting to be acknowledged or shunned, in many ways, Nathi’s life is one of limbo, of both life and death, and death’s inevitability frequently crops up, whether Nathi claims, “It’s still a long stretch of time before I die,” or plays games like Last Life, which “is the name we’ve come up with for what happens to me during my last year on the planet.”

The novel’s main antagonist arrives early in part two, when word arrives that a potential new client desires to purchase Nathi’s entire drug stash. The mystery man floods the group’s bank account with a life-changing amount of money and, to show his power and seriousness, he emails information to the three that proves he knows their identities. Though the idea of selling to only one client appeals to the trio, an underlying sense of menace from the man—and the possibility that he’s police—leaves the dealers on edge. With Nathi, Cecelia, and Ruan metaphorically pinned under the client’s thumb, it would be easy at this point for Ntshanga’s novel to devolve into a generic narrative of cat-and-mouse, yet such objectives never surface in The Reactive. Instead, this new assignment subverts expectations, leading to an unexpected, subdued climax, and it allows Nathi to reflect on his own past and come to terms with the death of his brother, Luthando, who expired at the hands of initiation school workers years earlier. As Nathi begins his engagement with his new client, he receives text messages from an estranged uncle, Bhut’ Vuyo, that urge him to return home. These notes, combined with the futility of his current lifestyle, open Nathi to ruminations on those he left behind. A short prologue reveals that Nathi blames himself for Luthando’s death: as teens, the two had planned on stowing away together at an initiation school (a multi-week excursion where each would be circumcised and achieved manhood), but Nathi stayed behind at the last minute, leaving his brother to go it alone. Luthando’s cutting, like many others, was botched, and his death inspired Nathi’s relocation to Cape Town, where he eventually shut his family from his life.

With The Reactive, Ntshanga seems less interested in writing a novel with a straight, linear plot than he is in writing one about overarching themes of family, denial, and disparity. By setting his narrative in the early 2000s, before the widespread availability of ARVs, Ntshanga entrenches his characters in a realm of political denial, which in turn results in physical denial, yet much of Nathi’s own narrative finds root in emotional renouncement: he refuses to consider a return to his family, shuns his uncle’s messages, and despite his own decent upbringing, he sabotages himself in order to reject a potential life of happiness. Early, Nathi admits that he, Cecelia, and Ruan are not stereotypical stoners, but that “each wrote matric in the country’s first batch of Model C” private schools. Ruan is a computer programmer; Cecelia works at a daycare center. Nathi went to university, worked in a lab testing strands of HIV, and was infected while on the job. The life he leads after becoming HIV-positive is chosen precisely because it allows him to deny himself happiness and upward progress. His guilty conscience prevents him from wanting success and promotes his limbo state. Without revealing too much, this same kind of denial eventually surfaces in The Reactive’s mysterious drug client subplot, as well.

Beyond thematic bonds, Ntshanga’s novel succeeds thanks to the author’s gift for language. Characters come to life via precise descriptions. For example, here’s how we meet Bhut’ Vuyo:

“Pushed forward by the locomotive of a lucrative Toyota scholarship, he’d gone to the city of Kyoto at the age of twenty-four, before coming back and accepting too many drinks on the house in a tavern called Silver’s.”

The economy on display here is enviable, for the reader is able to fully engage and understand Bhut’ Vuyo with only one sentence. And the sentence itself flows with a lyrical quality that continues throughout the novel. As Nathi tries to come down from a glue high, he notes, “The atmosphere feels warm and slippery on my skin, and my mind instructs me to glide, so I push my arms out and try to do that.” When speaking to prostitutes, Nathi mentions “how shattered their faces looked, as if they were the survivors of a protracted battle,” and as the group firsts encounters their severely burned and scarred mystery client, Ntshanga speaks volumes of the man’s physical appearance with Nathi’s unpretentious line, “If he’s smiling, then none of us can tell.”

It’s worth mentioning that this client also occasionally wears a tin mask to hide his true visage, and this literal idea of a man having two faces echoes metaphorically in Nathi’s life. Beyond the fact that he feels as if he’s missing part of himself without his brother, and beyond the multiple lives he has led, the protagonist is named after a girl, and the moniker, the reader is told, means “wait with us.” This definition inserts plurality directly into Lindanathi from birth, and as he struggles with the decision to return to visit his family, his multiple faces emerge.

Writing this review as a thirty-seven year old white male in the United States, I wonder why Nathi’s story strikes so close to my own emotions. And then I realize that, as a child of the 1980s, I grew up under the cowering fear of HIV, convinced in my youth that the infection was inevitable. That any shot or finger prick could spell disaster. I remember Ryan White and Ronald Reagan’s own denial. I was shaken when Freddie Mercury died, dumbfounded by Magic Johnson’s abrupt retirement announcement in 1991 and, come 1994, I rocked my No Alternative CD at top volume. In essence, I, like so many of my generation, have matured to the threatening rattle of HIV and AIDS, have seen the way it has been confused and unfairly stigmatized over four decades, and so, despite never having stepped foot on South African soil, there is an immediate recognition of, if not kinship, then memory that comes from engaging a novel like Masande Ntshanga’s The Reactive. This is a powerful, compassionate story that refuses to rest or shuffle off into the murk of the mind. It exists so that we never forget.

— Benjamin Woodard

.

Benjamin Woodard lives in Connecticut. His recent fiction has appeared in, or is forthcoming from, Storychord, Corium Magazine, and Maudlin House. In addition to Numéro Cinq, his nonfiction has been featured in, or is forthcoming from The Kenyon Review Online, Georgia Review, 5×5, and other fine publications. He also helps run Atlas and Alice Literary Magazine. You can find him at benjaminjwoodard.com and on Twitter.

.

Benjamin, I am reading your review in January 2022 after learning about Reactive in JM Jackson’s “The African Novel of Ideas.” Following my reading of the novel, as I usually do, I look for reviews that provide meaningful insights. In contrast to some reviews that I view as problematic, due to their reviewers having little sense of the field of African literature or define the book with cliches, I found your review stunningly on target—you noticed the significant themes of poverty, friendship, and renunciation; the lyrical quality of the author’s writing, and the drug/ alcohol stoked life of a protagonist who is worthy of compassion by his family as well as readers. I trust you are still writing reviews that honor the work of rising literary artists. Thank you for your thoughtful review at Numero Cinq.