The news reached us early in February that Sam Savage is dying. It is an immense and awful honour to be thus involved in an author’s final days. It comes to us because of Jeff Bursey’s relationship with Savage, a relationship based on multiple readings and reviews over the years and the magnificent and compendious interview Jeff did with Savage for our May 2015 issue (“It Is Not a Novelist’s Job to be Merciful: An Interview with Sam Savage”). In the days that followed, Jeff was in touch with Savage about a retrospective essay we intended to publish. Savage sent us a new unpublished short story to go with that essay. And then, amazingly, Savage sent us his entire Collected Poems, most of which have never been published, many of which are brilliant (I absolutely adore the comic sequence called “The Kiffler Poems,” which forms the last third of the book). Thus we have for you today Jeff Bursey’s retrospective essay on the works of Sam Savage, a short story by Savage, and his complete Collected Poems.

I don’t know Sam Savage except through his work and through Jeff Bursey, which is a lot when you come to think of it. But I think of him reading these words in his bed, and the moment seems holy. Thank you, Sam.

dg

.

Introduction

Sam Savage has a genius for getting inside his characters’ heads and bringing out their worst and best traits in such a way that we are never in doubt that the individual—it can be man or woman or, yes, animal—is a presence who has felt pain and sorrow and has a story to tell. His lead characters are intensely believable because the language is intense and believable. This exquisite combination of words and psychology, along with Savage’s knowing penchant for idiosyncratic behaviour, is rare indeed, not found in fiction as frequently as we might desire.

A brief overview

Part of the appeal of Sam’s novels is enjoying the control displayed as his characters do things you would not expect, but that make perfect sense within their own way of being in the world. Each book features a voice (“a way of speaking, a way of seeing the world from an angle so specific that it defines the character of the person who is viewing the world in that way,” as he defined it in the interview he did for Numéro Cinq in May 2015), a set of restraints, and a major task (it may appear trivial or obsessive or disturbed to outsiders) that consumes the positive energy of the narrator. While it might seem easy to convey the type of claustrophobia that comes from situating events and impressions in one mind, it is another level of difficulty to keep that from becoming dull for the reader as the character flails about and retreats further from sociability, competency, and normal manners. Offsetting the potential for the reading experience to turn oppressive is the presence of humour (aggressive or dark more often than gentle or whimsical) and compassion. These elements are handled with firmness and skillfully, always allowing a sufficient amount of space between authorial command and the apparent free agency of a character to move quickly from one activity or mood to another.

It’s partly the purpose of this essay to underscore those and other achievements of a truly fine novelist. Think of this as a reminder, or an alert, to the existence of someone who deserves respect for his art.

Correspondence and interview

Sam was born 9 November 1940; our first exchange occurred in October 2010. So there’s no great depth of knowledge that I’ll draw from here. I also won’t claim to not sound awkward when writing him. We’ve exchanged a few opinions on books, on readers, on the economy, on the Internet, and so on. When I saw a short piece by him in the Winter 2014 issue of Paris Review I asked, in January 2015, if this was part of a new novel. No, just a short story. Had he given up novel writing? His answer had the same bracing absence of self-pity as his fiction: “Well, Jeff, I am 74 years old and in bad health. I don’t have the courage or stamina for another novel. Not a voluntary retirement from writing but simply a recognition of the facts.” Not a case of overstatement and no hint that amplification would come. Either he isn’t like that or, more likely, he’s not like that with some guy he’s never met sitting at a computer northeast of his home, I thought. He is as reticent when it comes to leaving materials behind for biographers: “… I receive few letters, and don’t keep most, and write even fewer. Mostly emails, which I intend to delete before the axe falls. I’d like to leave no trace except my novels.”

Provoked by his health statement to act, in February 2015 I sent Sam the first set of interview questions with the aim of getting more down than the “trace” of his novels for those who, like me, wanted to know about the mind that created them. At the end he summed things up this way: “It has been a long haul, but I am grateful for the chance to address some of the issues you raise. I do think that not many people get where I am coming from, and perhaps this will help a little. And, I am sure, what was long for me was three times as long for you. So thank you.” Of course, the month-long process didn’t seem arduous to me as I found his answers fascinating.

When I first read Firmin I thought that here was a new and supple voice that was capable of wringing pity from vermin. Sloth cemented my appreciation of his talent. Sam’s books are filled with obsessions, a loneliness that is at times terrifying, a devotion to form and voice, and, above all, an underlying humanity that deserves comparison to the works of Joseph McElroy and Gabriel Josipovici. We read of a mind destabilizing and threatening not to be there much longer, and the tension of what’s going on, or what may be revealed in a few lines or at the top of the next page combines with the haphazard (almost leisurely, if that doesn’t sound peculiar) self-exploration of the narrators who cannot help but go on about themselves as they drive (or are driven) towards some shattering, final obstacle.

In the NC interview Sam talks about living with his wife in Madison, Wisconsin, versus the South where he was born: “I work. I used to take walks in the neighborhood. Now I look out the window. In the warmer seasons Nora and I go out to lunch once or twice a week. My sons come for long visits every year. Friends come from South Carolina and from France. I don’t know anybody in Madison apart from neighbors, a couple of Nora’s friends, and doctors. I can hardly be said to live here. I feel I am just passing through, practically unobserved, like a ghost.” It’s the ghostliness of his books—that they may become pale and unseen except by a few souls—which this essay is trying to address.

News I didn’t want to hear

In the interview Sam addressed his health. He had learned in the 1970s that he has alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, and this means he’s “…missing a blood component that protects the lungs from attack by some of the body’s own enzymes. The consequences vary widely. Chief among the more serious are liver failure and lung destruction…. It’s an ineluctable, irreversible process.” The expectancy of life ending soon is a feature of his novels. “There was a long period, in my twenties and early thirties, before I became really noticeably sick, when awareness of death in the form of a boundless encompassing dread was so persistent and unbearable that I contemplated suicide in order to escape it… Maybe being sick—and during the last twenty years quite obviously so—has made me more sensitive to the blitheness with which we normally—and I suppose I can say mercifully—go about the business of living.” Looking on things now, I should not have been surprised by what he had to say.

A note on 4 February 2016 spelt out matters with Sam’s usual lack of sentimentality and matter-of-factness: “I was hospitalized for a time in November and on discharge was put into a special Medicare category called Hospice designed for those deemed to have fewer than six months to live, where all restrictions are lifted on morphine and such. In other words, I am dying, and rather rapidly. I am unlikely to live out the six months. In my view I won’t even get close.” He’s not the type to draw attention to his own—well, he’d probably never say plight unless it suited a character, and so I’ll say this turn. “I have no inclination to keep it secret and am prepared to do anything I still can to give my books a chance to live on without me.” At the same time as he expresses what’s taken 40-some years to draw so very near, he writes about it not quite casually, but without self-indulgence, not wanting anything for himself, precisely, but advocating for his art. He knows what creating those novels demanded and required. Most writers, most artists, can identify with that.

Novels

In an effort to pay respect to this artist’s life’s work, then, here are selections taken from reviews I’ve written of his books for various journals to give readers an idea of their flavour. (One novel not considered is The Criminal Life of Effie O. [2005], which he’s dismissive about in the interview.) The hope is to encourage people to entertain this thought: that not reading Sam’s novels (all published by Coffee House Press) is a missed opportunity, something you won’t know you would have missed unless you read him.

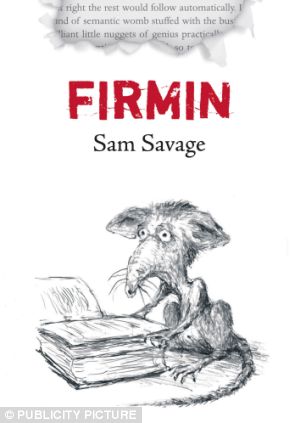

Firmin (2006; with thanks to Books in Canada.)

“Firmin gathers impressions of the world from novels, history books, and maps. He has a lot of knowledge which, because of his position, will never be put to use. He fails at sign language, learned from a slender pamphlet, the only time he gets to try it, and typing is impossible for him. He can play the piano, but this never helps him pick up girls. He prefers devouring books to anything else. An insatiable reader, he categorizes authors. In fiction, there are the Big Ones, like Joyce, Dostoyevsky, and Strindberg, from whom Firmin learns that ‘no matter how small you are, your madness can be as big as anyone’s.’

Firmin’s situation is complex, bizarre, and at times unutterably sad, due to his exceptional condition. He is a rat who was raised with literature for sustenance, in every sense of the word.

“. . . Airy grief in some way sums up Firmin’s predicament. It’s impossible to read Firmin and not contemplate what it’s like to be out of step with everyone, forever, and not through choice. This trim novel is a modest delight, with its clever conceit, an abiding respect for literature, and geniality co-existing with melancholy.”

The Cry of the Sloth (2009; with thanks to Open Letters Monthly.)

“In the delightfully mordant The Cry of the Sloth, Sam Savage gives us Andrew Whittaker, a lonely man, isolated by a failed marriage, his own misdeeds, and his often ugly personality. A bookish individual, editor and owner of a small-time journal named Soap, Whittaker bears rat-like teeth at his competition. He writes letters to his ex-wife, women he knew years before, contributors to the failing journal, and impatient bill collectors, and these letters make up the majority of the novel, with the occasional excerpt from a diary and passages from a novel Whittaker has underway. While the correspondence tells us that Whittaker is desperately trying to keep his magazine afloat, and is a failure at romance, the novel he’s writing illustrates his loneliness, bitterness, and sexual frustration. Though Savage limits us to Whittaker’s point of view and we therefore have only a one-sided version of events, it’s clear that by the end of The Cry of the Sloth we have witnessed the fairly rapid decline of Whittaker as he loses his friends, his family, his income, and control over his emotional and mental state.

“. . . In the midst of the systemic corruption of the Nixon years, Whittaker embodies, on a modest level, smallness and pettiness, and is a reminder of how easily we can turn, or naturally be, rotten to others while deluding ourselves about our own importance. The Cry of the Sloth is a fine example of the epistolary novel (another is Mark Dunn’s Ella Minnow Pea), and reminiscent of works that attempt to make someone who is unlikeable at least approachable (Joseph Heller’s Something Happened comes to mind). By focusing on a minor, carping, mean-spirited man, it shows that even an unedifying life can serve as a moral lesson.”

Glass (2011; with thanks to Requited)

“Like the figures in Firmin and Sloth, Edna looks to be completely on her own. One of the many accomplishments in this fine novel, saved for the last pages of Glass, and carefully led up to, is to make a reader come close to understanding the deadening sadness of her life, and potential fate, and, finally, feel sympathy for a character whose ways can be off-putting and obscure. One wonders if Sam Savage is indicating that we live in a Godless universe, with Edna just one more creature in a glass cage, unloved and not made to last. If so, then this is a chilling picture of old age and contemporary society.”

The Way of the Dog (2013; with thanks to The Winnipeg Review.)

“[This novel] begins quietly, like Savage’s other works, with readers closely following the mind of Harold Nivenson, a man of undisclosed age living alone in his crumbling home.

“. . . Hatred entered Nivenson’s life early on. His siblings would steal one piece from every puzzle he started, and even if he wasn’t sure they did, the anxiety that there would be a hole in the picture at the end ‘destroy[ed] the pleasure [he] might otherwise have derived from the puzzle.’ Without much more explanation, Nivenson says he ‘became, in my family and for my family, and ultimately for myself as well, the representation of failure.’ His sister and brother, due to the inaction of their parents, ‘bear the entire blame for my situation, a situation that amounts to a disability…’”

It Will End with Us (2014; with thanks to Numéro Cinq)

“Told through haphazard recollections, It Will End with Us portrays the Taggarts as troubled by the father’s offhand brutality… and the mother’s unraveling mind…, located within dire economic and environmental conditions. The myth of the fertile South is replaced with the reality of a parched region losing its resources—dusty land can’t bear crops, neither Eve nor Thornton produce children…, and the crumbling family home a rebuke to the prosperous Big House frequently featured in Southern history. Savage’s foray into Southern fiction bears some resemblance to Faulkner in its capturing of the deterioration of a self-important family and its host culture, but in Eve there is a larger theme at work, to my mind, than that of the decline of the South. She does not look back with self-pity. Whether we can trust her is open to question.

“. . . The integrity of the main character and of the story told, fascinating topics deftly handled, lead into another aspect of her that is equally rich. A character named Eve who focuses on a childhood when her family was intact invites us to entertain the possibility that this novel, certainly at one level about the mythical/real South, at a deeper level plays with religious myths through the creation of a Biblically-named figure from Spring Hope—a debased name for Eden—who is trying to retrieve a pre-lapsarian world that never existed.” (Full NC review is here.)

Final thoughts

To return to Sam’s news, which he has given permission to be shared, I asked him if he wanted to add something, in a public venue, about his impending death. Why did his answer surprise me? “I think I have nothing more to say.” There’s no appeal for sympathy over his state, no last explanation. In keeping with his integrity, Sam’s novels say what he would like to remain in our heads. They are the artistic achievements he has left standing, that he has left us, and which we have the wonderful prospect of reading and re-reading now and into the future.

— Jeff Bursey

.

Jeff Bursey is a literary critic and author of the picaresque novel Mirrors on which dust has fallen (Verbivoracious Press, 2015) and the political satire Verbatim: A Novel (Enfield & Wizenty, 2010), both of which take place in the same fictional Canadian province. His forthcoming book, Centring the Margins: Essays and Reviews (Zero Books, July 2016), is a collection of literary criticism that appeared in American Book Review, Books in Canada, The Review of Contemporary Fiction, The Quarterly Conversation, and The Winnipeg Review, among other places. He’s a Contributing Editor at The Winnipeg Review, an Associate Editor at Lee Thompson’s Galleon, and a Special Correspondent for Numéro Cinq. He makes his home on Prince Edward Island in Canada’s Far East.

Very moving piece. As is the way of our culture in these times, it is an heroic act to sing the unsung heroes for those who might otherwise hear them, and those who have all along. Fine work.

Thank you, Paul.

Thanks, Paul, for this comment.

Thank you, Jeff Bursey, for performing an important service critics often shy away from. I am grateful, too, to Sam Savage for his illustrious late career. I have no doubt that his work will be read and valued for many years to come, and on several continents. I hope he knows (I’m rather sure he does) in what esteem his original publisher at Coffee House Press, the late Alan Kornblum, held his work. It must have been ’07 or ’08 when Alan spoke to me with obvious pride and amazement at the bestselling success of “Firmin” in Italy. If it was a trifle less of a runaway hit in North America, that only proves that often as not you have to leave home to be properly appreciated.

Thanks, Bruce. I will check with Jeff to make sure Sam sees this.

Bruce, hello. Sam deserves much more attention than he’s received, so every good word about him, such as your comment, can help bring him more readers. Thanks for what you say.