(Photo: Theo Cote)

How does one introduce Lydia Davis? By listing her accolades (which include the 2013 Man Booker International Prize)? Her acclaimed story collections, like Samuel Johnson is Indignant and Varieties of Disturbance? Her exquisite translations of Proust and Flaubert?

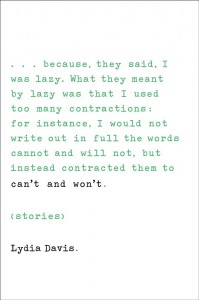

Since breaking through with Break it Down in 1986, Lydia Davis has stood at the forefront of American literature, constantly crafting fiction that both provokes reaction and mines the depths of the English language. In my review of her latest collection, Can’t and Won’t, I write, “The book is a remarkable, exhilarating beast: a collection that resumes the author’s overall style—short narratives, with the occasional longer piece—while simultaneously expanding her vision.” In addition, the translation work by Davis has both reintroduced classics (Madame Bovary) and ushered lesser known works into the libraries of avid readers.

It was a pleasure to connect with Ms. Davis for the following interview. We began speaking in February via email, and conducted this conversation over a series of electronic messages that lasted through the end of March.

— Benjamin Woodard

Benjamin Woodard (BW): The 14 “Flaubert stories” in Can’t and Won’t feel right at home with your other narratives, often echoing ideas and themes from other stories. Were you drawn to these while translating Madame Bovary, or did they come earlier?

Lydia Davis (LD): Actually, I stumbled upon them as I was reading through the letters that Flaubert wrote during the time he was working on Madame Bovary. The letters were interesting for many different reasons, but the nicest reward was to come upon a little self-contained story that he was telling his correspondent, about something that had happened to him recently. I took whatever liberties I needed to—these were not meant to be “straight” translations—and shaped them into little stories.

BW: How did you shape the narratives?

LD: Sometimes, I barely touched them. Usually, though, I would make little changes—combine two sentences or cut some material out of one. In the first story, about the cook, I added the phrase “and yet it has been five years since he left the throne”—because a contemporary American reader would not have the same information that Flaubert’s correspondent did as he wrote the letter. I tried to write this, and other additions, in Flaubert’s style and tone. In another story, I added some information about one of the characters, since he was otherwise unidentified. Yet another story, the one called “After You Left,” actually combines material from two letters. On his way home in the carriage, Flaubert remembers riding home on another occasion in a sleigh—in my story. In fact, he recounted that sleigh ride in another letter.

BW: Does translation work ever affect your style in English?

LD: Usually, for whatever reason, the style of the work I’m translating does not creep into my own—although I noticed when I was translating Proust that my emails became longer and more digressive. But I certainly like the little Dutch stories I’m translating at the moment, by A.L. Snijders, and I’m sure I will begin writing stories modeled on those, if I haven’t already.

BW: The “dream pieces” story cycle is another type of translation altogether. What prompted this cycle, and how did you decide to interpret these surreal tangents?

LD: What prompted these was a combination or confluence of two things—often the case. A French Surrealist and ethnographer, Michel Leiris, had published a book that collected his dreams over forty years. What interested me about this book was not just the dreams but that he included waking experiences that were like dreams. I had this book in an English translation by Richard Sieburth. It sat on my shelf for a long time. But then one day I had a waking experience that was so like a dream that it inspired me to see what I could do with narrating dreams so that they were dynamic and vivid, and narrating waking experiences so that they were believable as dreams.

BW: Does your approach differ when writing an extremely short piece like “Ph.D.” compared to “The Seals,” one of the collection’s longest stories?

LD: Oh, yes. Many of the shortest stories occur to me already almost complete—though not the one you mention, which was actually shortened from a longer “dream” piece. Often, all that these very short pieces need is the right title, and I take some time over finding that. But a long, fully developed narrative, like “The Seals,” requires going into a sort of trance, allowing the inner voice to begin speaking, and letting one paragraph suggest the next. There is a lot of material in a long story that was not planned in advance but that occurred during the writing. Then, there is the problem of structure, which I don’t really have in a very short story. Will one part balance another part in a good way? Is the conclusion thoughtful and strong? And in the case of that story, I had to pay attention to how often the narrator’s present situation, sitting on a train, came back into the story, so that it wasn’t lost. Much more complicated, altogether, than the shortest stories. But on the other hand, the shortest stories have that challenge of being substantial enough, in their few words, to carry full weight as finished pieces of writing.

BW: How does the idea of travel fit into your storytelling? Your characters often find themselves on physical journeys. For example, “The Seals” takes place on a train, alternating between present and past, in a way reminiscent of Thomas Bernhard’s The Loser.

LD: The simple fact is that I was traveling when I began many of these stories, since I find that sitting on a train or in an airplane is actually very conducive to letting my thoughts roam around freely in a relaxed sort of way, which sometimes produces a thought that leads to a story. At home, more stationary, I may be translating, or writing something non-fictional, like an essay. So the travel stories arise from incorporating what is going on at that moment. I like traveling—I like the feeling of suspension that one has at those times. You are between home and your destination, you are surrounded by strangers, you have a fellowship or bond with a group of strangers, for better or worse. It is very interesting. And often I am also in a foreign place, which means a foreign culture. I enjoy the contrast between that and my domestic, rural, home existence.

BW: Thematically, Can’t and Won’t plays quite a bit with the idea of capturing different forms of history, be it dreams or memories or subconscious realizations. Was this a deliberate effort on your part?

LD: Well, your insight is interesting—I rarely stand back and look at the pieces as a group. It is true that I’m very interested in history—as I never was in school. But as for a deliberate effort, no, I do not think ahead of time about themes. Stories occur as they want to occur—I try to impose as little as possible on them. They simply reflect whatever is on my mind at that time. Only sometimes, as in the case of the Flaubert stories or the dream stories, or the letters of complaint—of which there are five in the book—I see that there is a form I like and want to explore, to see what it might yield.

BW: Finally, what are you reading now? What writing inspires you?

LD: Interesting question. Actually, two quite different questions, possibly. I do keep reading the small stories of the Dutch writer Snijders—since he sends them out by email. And they inspire me to translate him. At the same time, I’m reading a biography of Glenn Gould, because he continues to fascinate me as pianist and person, and I want to know more about him. But that book would not inspire me to any kind of writing. W.G. Sebald’s novels inspire me—I’d like to do what he does; so do Thomas Bernhard’s, though he is so surpassingly negative about everything—but funny. There is a wonderful, probably not very well known thin book by the Canadian Elizabeth Smart with one of the best titles I know: By Grand Central Station I Sat Down and Wept. It is a story of obsessive love, and it is most eccentrically written. I know that title will seep into me and come out somewhere, sometime, and maybe the structure and style of book itself will, too.

— Lydia Davis & Benjamin Woodard

.

Lydia Davis is the author of one novel and seven story collections. Her collection Varieties of Disturbance: Stories was a finalist for the 2007 National Book Award. She is the recipient of a MacArthur fellowship, the American Academy of Arts and Letters’ Award of Merit Medal, and was named a Chevalier of the Order of the Arts and Letters by the French government for her fiction and her translations of modern writers, including Maurice Blanchot, Michel Leiris, and Marcel Proust. Lydia Davis is the winner of the 2013 Man Booker International Prize.

.

Benjamin Woodard lives in Connecticut. His recent fiction has appeared in decomP magazinE, Cleaver Magazine, and Numéro Cinq. His reviews, interviews, and essays have been featured in Publishers Weekly, BuzzFeed Books, Numéro Cinq, Rain Taxi Review of Books, The Bygone Bureau, and other fine publications. He is a member of the National Book Critics Circle. You can find him at benjaminjwoodard.com and on Twitter @woodardwriter.