122 stories make up the volume, broken into 5 sections, and throughout, pockets of theme gradually surface—travel, loss, subconscious thought—and ostensibly unrelated pieces lock together to form intriguing puzzles that call into question life, happiness, and memory. — Benjamin Woodard

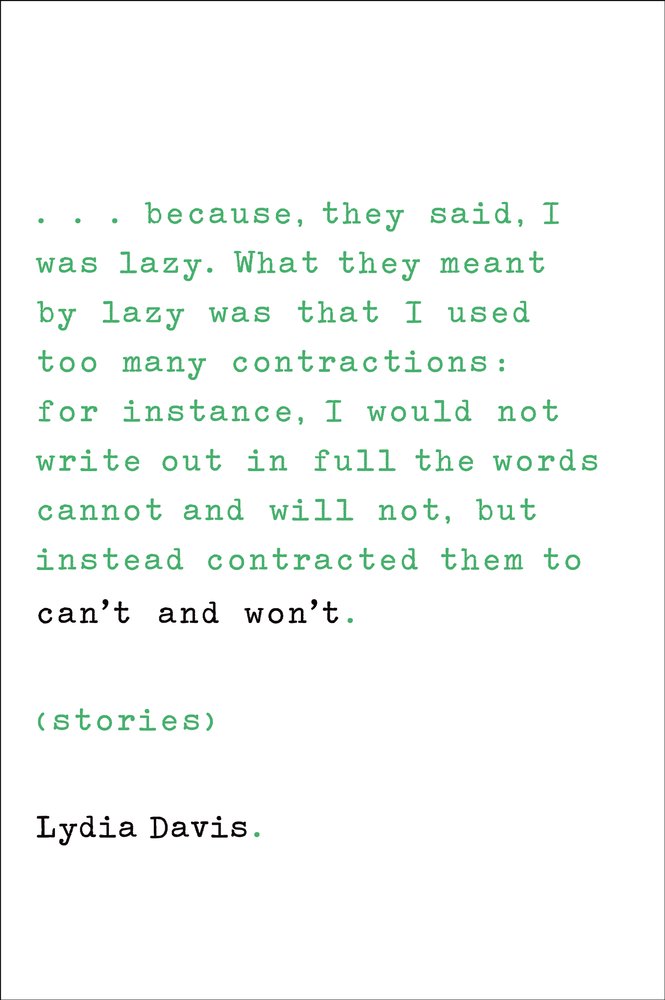

Can’t and Won’t

Lydia Davis

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

256 pages ($23.00)

ISBN 978-0-374-11858-7

T

he stories of Lydia Davis tend to challenge the general notion of what most consider “story,” rarely following a recognizable structure—rising action, climax, dénouement—and instead focusing on brief moments and recollections, some of which take up no more than a single line of text. Because of this, Davis’s narratives hew closer to that of vignette or prose poem than fiction, lyrical interludes designed to impact without the fuss of narrative webbing. But while this argument holds weight visually, it falters in that it constrains the idea of fiction to that of firm rules and chartered courses, muffling the elasticity and wonder of storytelling. In a 2008 interview with The Believer, Davis defined “story” as any writing with “a bit of narrative, if only ‘she says,’ and then enough of a creation of a different time and place to transport the reader.” This classification is a fine way of looking at the oeuvre of the author herself, for though her stories always contain some form of protagonist—even if said protagonist is the speaker of the story’s lone sentence—they purposefully dodge other expectations, shuttling the reader into an unfettered territory of language and verbal exploration. In Can’t and Won’t, Davis’s fifth collection, due out next month, the author continues to push the boundaries of narrative. The book is a remarkable, exhilarating beast: a collection that resumes the author’s overall style—short narratives, with the occasional longer piece—while simultaneously expanding her vision. 122 stories make up the volume, broken into 5 sections, and throughout, pockets of theme gradually surface—travel, loss, subconscious thought—and ostensibly unrelated pieces lock together to form intriguing puzzles that call into question life, happiness, and memory.

Two story cycles, peppered throughout the text, anchor Can’t and Won’t. Both are quite strong, and in each, Davis plays with the concept of preserving the past. In the first, “dream pieces,” snippet narratives recall the nocturnal fantasies of Davis and her family and friends. These are, as one might expect, odd, but they permit Davis, so often clinging to the tangible, the opportunity to stray from reality, to bend the “regular” world. In “At the Bank,” patrons win cheap arcade prizes for guessing the correct amount of change in their deposits (“…I choose what I think is the best of them, a handsome Frisbee with its own carrying case.”). “The Piano Lesson” concerns a woman wishing to learn piano from her friend. She is given the assignment of learning several pieces, with the plan of meeting in one year’s time for the actual lesson. And “Swimming in Egypt” explores deep-sea tunnels that lead to the Mediterranean. What’s so very interesting about these stories is that, like all dreams, they contain unspoken meaning and do not follow logic. Still, Davis meets all moments of absurdity with complete seriousness, presenting each vision with little embellishment, acting as agent between the cerebral and the page, refusing to attach meaning, or to shape each discharge into a clear picture. As a result, these pieces float as if engulfed in haze, clues to an unknown psyche, snapshots of moments originally intended to not live on, but to evaporate with wakefulness.

Conversely, “Stories from Flaubert,” a 14 story sequence composed of material culled from letters between Gustave Flaubert and his lover, Louise Colet, sees Davis again seizing upon past events, but using these junctures to create parallels between old and new, breathing life into moments of universal emotion. Translated, modified, and arranged by the author, these works both capture the language of Flaubert and remain complimentary to Davis’s modern narratives. Narrative echoes between the two allow Davis to reach across 160 years and demonstrate how little human thought and reaction have matured, how, regardless of advancement, there are many questions—particularly those of the mind, of life and death—that endure, haunting the human condition. One striking example of this comes in “The Visit to the Dentist,” in which Flaubert, after travelling to have a tooth pulled, passing through a former execution ground, is haunted by his subconscious, which fills his head with images of the guillotine. This same process of storytelling—building through subconscious connection—flourishes in Davis’s non-Flaubert story, “The Force of the Subliminal,” where a conversation about birthdays sparks a series of triggers, leading the protagonist to interrogate the path in which she processes thought.

A beautiful illustration of Davis’s writing at its sharpest, and perhaps most accessible, comes in the story “The Language of Things in the House.” Here, funny, playful translations of the noises produced by household items (“Pots and dishes rattling in the sink: ‘Tobacco, tobacco.’”) find juxtaposition with italicized passages of narration trying to make sense of each translation:

Maybe the words we hear spoken by the things in our house are words already in our brain from our reading; or from what we have been hearing on the radio or talking about to each other; or from what we often read out the car window, as for instance the sign of Cumberland Farms; or they are simply words we have always liked, such as Roanoke (as in Virginia).

The result is a story with equal parts humor and gravity, one that introduces ideas of language and compels the reader to acknowledge and consider the way in which we as a people go about daily routine. Again, the concept of subconscious thought returns, creating another narrative echo, but the piece also, and this is something Davis is extraordinary at, paints a story within the blankness of the overall narrative, for the lack of information concerning the narrator (is it Davis? someone else?) creates a vacuum that requires the reader to mentally construct the life of the speaker. The point of the narrative is less that of the written text—though the written text is quite intriguing—and more that of the person writing.

Can’t and Won’t’s numerous fictional complaint letters—at 6, there are nearly enough to qualify as a third story cycle—continue to exploit the concept of “the writer” behind the story. In all but one—“The Letter to the Foundation,” at 28 pages, fills in most narrative gaps—the intention is not to present the reader with a list of why, say, a vegetable manufacturer should redesign its packaging (“Letter to a Frozen Peas Manufacturer”), or to submit to a confectionary company evidence of weight shaving in its products (“Letter to a Peppermint Candy Company”), but rather to create curiosity in who exactly would write such letters, as in “Letter to the President of the American Biographical Institute, Inc.,” where “Lydia Davis” takes umbrage with a company peddling a paid-inclusion vanity compendium:

You said that in researching my qualifications, you were assisted by a Board of Advisors consisting of 10,000 “influential” people living in seventy-five countries. Yet even after this extensive research, you have made a basic factual mistake and addressed your letter, not to Lydia Davis, which is my name, but to Lydia Danj.

The passage is deadpan comic, yet it further raises questions as to the motivations of the writer. Why, exactly, would someone take the time to write such a missive? What does this say about “Lydia Davis,” the character? Why enshrine this particular sliver of history through word? When examining these narratives with such a thought in place, each letter gains an enormous amount of dramatic heft, shaking away any coldness presented in the calculated, measured physical text. This abutment grants an immense amount of pleasure, and a slight case of uneasiness, for the unknown writer—mysterious, eccentric—lingers long after the story has completed.

At the center of Can’t and Won’t is a long story called “The Seals.” Like a distant cousin of Thomas Bernhard’s novel, The Loser, the story covers a very short amount of present time—in this case, a portion of a train ride down the East Coast—yet delves deep into memories, constructing for the reader a solid, palpable relationship between a woman and her deceased family members. As Davis’s protagonist, entombed in a train car, periodically moves or looks out the window, she recalls her sister and father, and the combination of real-time experience and remembrance is highly effective, providing Davis a showcase to meditate on the idea of bereavement. At one point, her character proclaims to the reader:

That fall, after the summer when they both died, she and my father, there was a point when I wanted to say to them, All right, you have died, I know that, and you’ve been dead for a while, we have all absorbed this and we’ve explored the feelings we had at first, in reaction to it, surprising feelings, some of them, and the feelings we’re having now that a few months have gone by—but now it’s time for you to come back. You have been away long enough.

This decree, both heartbreaking and selfish, cuts to the bone and drives the narrative, yet the sentiment acts as an umbrella shading the entirety of the collection. For with Can’t and Won’t, Davis deftly hones the art of looking backward, of calling the dead to life, of retaining the moments in life intended to remain fleeting. The result is a tapestry of method, style, and structure, all with the same objective: to possess that which has passed, to capture the lost and the unidentifiable.

Benjamin Woodard lives in Connecticut. His recent fiction has appeared in decomP magazinE, Cleaver Magazine, and Numéro Cinq. His reviews and interviews have been featured in Numéro Cinq, Publishers Weekly, Rain Taxi Review of Books, and other fine publications. He is a member of the National Book Critics Circle. You can find him at benjaminjwoodard.com and on Twitter.