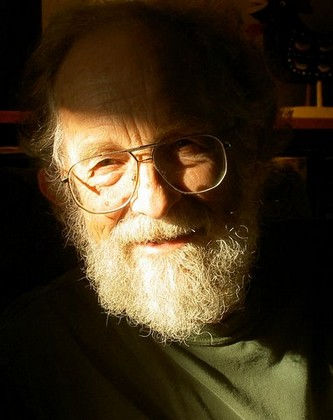

It’s a great honour to unveil on these e-pages David Helwig‘s new translation of Anton Chekhov’s story “About Love.” David Helwig is an old friend, a prolific author and translator, and a mighty gray eminence on the Canadian literary scene. In 2007 he won the Writers’ Trust of Canada Matt Cohen Prize for distinguished lifetime achievement. In 2009 he was appointed to the Order of Canada. His book publication list is as long as your arm. He founded the annual Best Canadian Stories which he edited for years. He is the author of an earlier book of translations, Last Stories of Anton Chekhov.

This post includes Helwig’s introduction to his new book of Chekhov stories and the story “About Love.”

dg

/

Anton Chekhov spent the winter of 1897-98 in France, most of it in Nice on the Côte d’Azur. He was avoiding the cold and damp of the Russian winter. In March of 1897 he had suffered a severe haemorrhage and was told that both his lungs were tubercular. Though he himself was a doctor he had for the previous ten years succeeded in ignoring the symptoms of his disease. Now he could no longer evade the medical facts.

That winter Chekhov read extensively in French and was much impressed by Émile Zola’s public intervention in the Dreyfus scandal. (One suspects that the little anecdote in ‘About Love’ concerning the supposed Jewish gangsters might have its origins in this.) Chekhov improved his knowledge of the French language—he was interviewed about the Dreyfus affair in French—but he did only a limited amount of writing. In May of 1998 he returned to his estate at Melikhovo, and in July and August he published in the magazine Russian Thought the three connected stories translated here. A year later he described them as a series still far from complete, but he never returned to them, and they remain his only experiment in linking his stories.

Within an overall narrative about the travels in the Russian countryside of the veterinarian Ivan Ivanych and the teacher Burkin, Chekhov presents three framed tales, the first a kind of grotesque comedy of the sort associated with Gogol, the second not dissimilar but with a more explicit and impassioned response from its narrator, the third a poignant little story of failed love that may evoke for the reader Chekhov’s most famous story, “The Lady with a Little Dog.” Emotion grows more personal as we move from one to the next. In the first story Burkin tells a tale about an acquaintance. In the second Ivan Ivanych tells about his brother. In the third their friend Alyokin tells a story about his own life.

While the framed tales provide the dramatic core of each story, the framing narrative offers a vivid evocation of the Russian countryside, with a sense of history and geography complementing and containing the urgency of the tales. In ‘Gooseberries’ an extraordinary passage describes the aging veterinarian Ivan Ivanych swimming in a cold mill pond, unwilling to stop, in the grip of some inexplicable joy; then at a paragraph break the story modulates in a single line to a quiet sitting room where the framed portraits of soldiers and fine ladies evoke a past gentility, and Ivan Ivanych begins to talk about his brother’s life, its obsession, the crude and joyless littleness of his achievement.

A passage from the conclusion of the first story lifts our gaze from the events we’ve just been told about. “When, on a moonlit night, you see a wide village street with its peasant houses, haystacks, sleeping willows, tranquillity enters the soul; in this calm, wrapped in the shade of night, free from struggle, anxiety and passion, everything is gentle, wistful, beautiful, and it seems that the stars are watching over it tenderly and with love, and that this is taking place somewhere unearthly, and that all is well.”

The point of view in Chekhov’s stories can be slippery. The “you” of this passage is unidentified but the verb is in the second person singular; it speaks intimately from some detached narrative intelligence to each single reader. The passage gives the sense of a benign universe surrounding the events.

Yet just a few lines earlier we have read Burkin’s harsh conclusion to the tale he has been recounting. “We came back from the cemetery in a good mood. But that went on no more than a week, and life flowed by just as before, harsh, dull, stupid life, nothing to stop it going round and round, everything unresolved; things didn’t get better.”

Such a counterpoint of one voice with another, one mood with another, their contradiction, suggests a subtle ironic interplay not altogether unlike the form of Chekhov’s plays. Always, in Chekhov, there is a sense that the events evoke other possibilities, offstage or after the narrative ends. The very last line of ‘About Love’, the third of these stories, offers a grim hint at what might be still to come.

In 1991 Oberon Press published Last Stories, my translations of the final six stories of Anton Chekhov’s career, including two or three of his finest and best known works. It seems appropriate to repeat here what I said in the introduction to that book, that while there are a great many translators whose Russian is better than mine, there are not so many who have had a long experience of writing narrative prose. These narratives are my personal versions of Chekhov’s stories; they are also as close as I can make them to the precision and suggestiveness of the originals.

–David Helwig

About Love

By Anton Chekhov

Translated by David Helwig

The next day for lunch they were served delicious meat turnovers, crayfish, and lamb cutlets, and while they were eating, Nikanor the cook came upstairs to ask what the guests wanted for dinner. He was a man of middling height with a pudgy face and little eyes, clean shaven, with whiskers that looked not so much shaved as plucked out.

Alyokhin told them that the beautiful Pelageya was in love with this cook. Since he was a drinker with a violent temper, she didn’t want to marry him, but offered to live with him all the same. But he was very pious, and his religious principles wouldn’t allow him to live like that. He insisted that she marry him—he would have nothing else—and when he was drinking he berated her, even hit her. When he was drinking she hid upstairs, sobbing, and then Alyokhin and his servant wouldn’t leave the house, so they could defend her if necessary.

They began to talk about love.

“How love comes into being,” Alyokhin said, “why Pelageya didn’t fall in love with some other man more suitable for her, with her inner and outward qualities, but instead chose to love that mug Nikanor”—everyone called him the ugly mug— “since what matters in love is personal happiness, it’s beyond all knowing, say what you like about it. Up till now we have only this irrefutable truth about love—‘It’s a sheer, utter mystery,’— every other single thing that has been said or written about it is not an answer but a reframing of the question—which remains unresolved. The explanation which would seem to be suitable in one case won’t suit in ten others, so what’s much the best, in my judgment, is to explain each case separately, not attempting to generalize. What we need, as the doctors say, is to individualize each separate case.”

“Absolutely right,” Burkin agreed.

“We respectable Russians nourish a predilection for these questions, but we have no answers. Usually love is poeticized, adorned with roses and nightingales, but we Russians have to dress up our love with fatal questions, and chances are we’ll pick out the most uninteresting. In Moscow when I was still a student I had a girl in my life, sweet, ladylike, but every time I took her in my arms, she thought about what monthly allowance I’d give her and what a pound of suet cost that day. Really! And when we’re in love we don’t stop asking ourselves these questions: sincere or insincere, wise or foolish, what our love is revealing, and so on and on. Whether this is good or bad I don’t know, what it gets in the way of, fails to satisfy, irritates, I just don’t know.”

It was like this when he had something he wanted to talk about. With people living alone there was always some such thing in their thoughts, something they were eager to talk about. In the city bachelors went to the baths or the restaurants on purpose just so they could chat or sometimes tell their so-interesting stories to the attendants or the waiters, and then in the country they habitually poured out their thoughts to their guests. At that moment what you could see outside the window was a grey sky and trees wet with rain; in this weather there was no place to go and nothing remained but to tell stories and listen to them.

“I’ve been living at Sophina and busy with the farm for a long time now,” began Alyokhin, “ever since I finished university. By education I’m a gentleman, by inclination a thinking man, but when I arrived here at the estate, it carried a big debt, since my father had borrowed money, partly because he spent a lot on my education, so I decided not to leave here, but to work until I paid off the debt. I made the decision and started in to work, not, I confess, without a certain repugnance. The land here doesn’t produce much, and for agriculture not to be a losing proposition it’s necessary to profit by the labour of serfs—or hired hands which is about the same thing—or to farm in the peasant way, which means working in the fields yourself alongside your family. There’s no middle way here. But I didn’t shilly-shally. I didn’t leave a scrap of land untouched. I dragged in every peasant man and woman from the neighbouring villages; work here was always at a raging boil. Myself, I ploughed, sowed, cut the grain; when I grew bored I wrinkled up my face like a farm cat who’s eaten cucumber from the vegetable garden. My body ached and I slept on my feet. At the beginning it seemed to me that I could easily reconcile this labouring life with my educated habits—all that counts, I thought, is to behave with a certain outward order. I settled upstairs here in the splendid reception rooms, and I curtained them off so that after lunch or dinner I was served coffee and liqueurs, and at night while I was lying down to sleep I read the European Herald. But one day our priest arrived, Father Ivan, and he drank all the liqueurs at one go, and the European Herald went to the priest’s daughters. In summer, especially during hay-making, I didn’t have time to get to my own bed, I’d take cover in a shed, on a stone boat, or somewhere in a forester’s hut—but why go on about it? Little by little I moved downstairs, I began to eat the servants’ kitchen; all that remained to me from our former luxury was those servants who had worked for my father, and to discharge them would have been painful.

In those first years here I was chosen honourary justice of the peace. Whenever I had occasion to go into the city, I’d take part in the session of the district law court; it was a diversion for me. When you go on here without a break for two or three months, especially in the winter, in the end you get to pining for your black frock coat. And at the district court there were frock coats, full dress coats and tail coats, and there were lawyers, men who’d received the usual education: I’d get into conversation with them. After sleeping on a stone boat, after sitting in a chair in the servants’ kitchen, to be in clean linen, light boots, with a chain on my breast—this was real luxury!

In the city they received me amicably. I was ready to make acquaintances, and out of them all, the soundest, and to tell the truth the most pleasant for me, was a friendly connection with Luganovich, the cordial Chairman of the district court. An attractive personality: you both know him. This was right after the famous affair of the arsonists; the trial lasted two days, we were tired out. Luganovich looked at me and said, ‘You know what? You should come to dinner.’

This was unexpected since beside Luganovich I was of little significance, just some functionary, and I had never been at his home. I stopped off in my room for just a moment to change my clothes, and we set off for dinner. And there the opportunity presented itself to make the acquaintaince of Anna Alexeyevna, Luganovich’s wife. She was still very young then, not more than 22 years old, and half a year later she was to have her first child. The past is past, and right now I’d find it difficult to define exactly what it was about her that was unusual, what it was in her I liked so much, but over dinner everything was irresistably fine. I was seeing a young woman, beautiful, good, cultured, charming, a woman I’d never met, and right away I felt a sensation of familiarity, as if I’d seen her before—that face, those clever, friendly eyes—in an album that lay on my mother’s dresser.

In the arson case we’d prosecuted four Jews, supposed to be a criminal gang, but as far as I could see, quite groundlessly. At dinner, I was very worked up, finding it all painful, I don’t remember now what I said, only when I spoke Anna Alexeyevna turned her head and said to her husband, ‘What is all this, Dmitri?’

Luganovich, that good soul, was one of those ingenuous men who hold firmly to the opinion that if a man is brought to court it means he’s guilty, and that to question the rightness of a sentence may only be done by legitimate procedures on paper and certainly not over dinner and in a private conversation.

‘We weren’t on hand with them to set the fire,’ he said softly, ‘and we’re not in court here to see them sentenced to prison.’

And both of them, husband and wife, did their best to get me to eat and drink a little more. By small things—this, for example, that they made coffee together, and this, how they understood each other in a flash—I could grasp that they lived comfortably, in harmony, and that they were glad to have a guest. After dinner they played piano four hands, then later on it grew dark and I set off home. That was at the beginning of spring. Subsequently I passed the whole summer at Sophina, without a break, and there was not a moment for a passing thought about the city, but the memory of the well-proportioned, fair-haired woman stayed with me all day; I didn’t think about her, but truly, her sweet shadow lay on my soul.

In the late fall there was a charity performance in the city. I entered the governor’s loge—I was invited there during the intermission—and I saw, down the row with the governor’s party, Anna Alexeyevna—once again, irresistably, the intense impression of beauty, and the sweet, tender eyes, once again the sense of closeness.

We were seated side by side, then we started out to the foyer.

‘You’re losing weight,’ she said, ‘are you sick?’

‘Yes. I’ve caught a chill in my shoulder, and in the rainy weather I have trouble sleeping.’

‘You have a dull look about you. In the spring when you came to dinner, you were younger, more cheerful. In those days you were enthusiastic, always talking, and you were very interesting, and I confess I was even a tiny bit taken with you. Often as the year went by you came to mind for some reason, and today when I was getting ready for the theatre it seemed to me that I’d see you.’

And she laughed.

‘But today you have that dull look,’ she repeated. ‘It ages you.”

The next day I had lunch at the Luganovichs’. After lunch they left the house to go out to their summer place to put things in order for the winter, and I with them. And with them I returned to the city, and at midnight I drank tea in the quietness of their house, those domestic surroundings, as the fireplace burned, and the young mother kept going out of the room to see if her daughter was asleep. And after that with each arrival I was, without fail, at the Luganovich house. They expected it of me, and it was my habit. Usually I entered without being announced, like someone who lived there.

‘Who is it?’ I heard from a distant room the drawling voice that seemed to me so beautiful.

‘It’s Pavel Konstantinich,’ answered the housemaid or the nurse.

Anna Alexeyevna came out to me with a worried look, and every time she asked, ‘Why have you been away so long? Has something happened?’

Her glance, the fine, graceful hands which she reached out to me, her everyday clothes, the way she did her hair, the voice, her step, each time all of this produced an impression of something new, extraordinary in my life, and important. We talked for hours and we were silent for hours, each thinking our own thoughts, or she played the piano for me. If no one was at home, I stayed on and waited, chatted with the nurse, played with the baby, or I lay in the study on the Turkish divan and read the newspaper, and when Anna Alexeyevna returned, I greeted her as she came in, took from her all her shopping, and for some reason, each time I took the shopping it was with as much love and exultation as a young boy.

There is a proverb: if an old woman has no problems, she’ll buy a piglet. The Luganovichs had no problems so they made a friend out of me. If I didn’t go to town for a while, that meant I was sick or something had happened to me, and both of them grew terribly anxious. They worried that I, an educated person who knew languages, lived in the country instead of occupying myself with science or serious literary work, went round like a squirrel in a cage, worked a lot but never had a penny. To them it seemed that I must be suffering, and if I chatted, appeared confident, ate well, it must be in an attempt at concealing my suffering, and even in happy moments, when everything was fine with me, I had the sense of their searching looks. They were especially full of concern when I was actually having a hard time of it, when one creditor or another oppressed me or when money was insufficient for the payments demanded; husband and wife whispered together by the window, and in a while he’d come up to me and say, with a serious look, ‘Pavel Konstantanich, if at present you should be in need of money, then my wife and I beg you not to feel shy, but to apply to us.’

And his ears grew red with embarrassment. That’s just how it would happen, the whispering by the window and he would come toward me with red ears and say, ‘My wife and I beg you earnestly to accept this present from us.’

Then he gave me some cufflinks, a cigarette case, or a lamp; and in response to this I would send from the country a dressed fowl, butter, flowers. It is to the point to say that both of them were well to do. From the first I had borrowed money and wasn’t especially fastidious, borrowed where I could, but no power on earth would make me borrow from the Luganovichs. That’s all there is to be said about that!

I was wretched. At home in the field or in a shed I thought about her, and I tried to see through the mystery of this young, beautiful, intelligent woman married to an uninteresting man, almost old—the husband was over forty—and bearing his children. How to understand the mystery of this uninteresting man, a good soul, a simple heart, who deliberated with such boring sobriety at balls and evening parties, took his place among reliable people, listless, superfluous, with a humble, apathetic expression, as if they might have brought him there for sale, who all the same believed in his right to be contented, to have children with her, and I struggled to understand why she was his and not mine, and why it must be that such a terrible mistake ruled our lives.

Arriving in the city, I saw in her eyes each time that she had been waiting for me; she herself confessed to me that whenever she perceived something unusual outside her window she guessed that I was arriving. We talked for hours or were silent, but we didn’t confess to each other that we were in love, but shyly, jealously, we dissembled. We were afraid of anything that might reveal our secret, even to ourselves. I loved her tenderly, deeply, but I debated, questioned myself about what our love might lead to if our strength wasn’t sufficient for the battle against it; it seemed to me incredible that this calm melancholy love of mine might suddenly tear apart the happy, pleasing course of life of her husband and children, of everything in that home, where they loved and trusted me so. Was this a decent thing to do? She would come to me, but where? Where could I take her away? It would be another thing altogether if mine were a pleasant, interesting life, if for example I were struggling to emancipate my native land, were a famous scholar, artist, painter, but no, I would carry her out of an ordinary, dull condition to another much the same, or to something even more humdrum. And how long would our happiness last? What would happen to her in case of my illness, death, or if we should simply stop loving each other?

And she, apparently was having the same thoughts. She considered her husband, her children, her mother who loved the husband like a son. If she should give herself up to her feelings, then she would have to tell lies about her state or to speak the truth, and either one would be awkward and horrible. And this question tormented her: should she offer me happiness, her love, or not complicate my life, already difficult, full of every kind of unhappiness? It seemed to her that she was already insufficiently youthful for me, insufficiently industrious and energetic to start a new life; she often talked to her husband about it—how I needed to marry a clever, worthy girl who would be a good housewife, a helper—and at once added that in the whole city such a girl was hardly to be found.

Meanwhile the years passed. Anna Alexeyevna now had two children. When I arrived at the Luganovichs’ the maid smiled pleasantly, the children shouted that Uncle Pavel Konstantinich had arrived and wrapped their arms round my neck, and everyone was glad. They didn’t understand what was going on in my soul, and they thought that I too was glad. They all saw in me a noble being. Both the adults and the children believed that some noble being had entered the room and this induced in them an attitude of particular delight with me, as if in my presence their life was finer and more pleasant. Anna Alexeyevna and I went to the theatre together, always on foot; we sat in the row of chairs with our shoulders touching. In silence I took from her hand the opera glasses, and at that moment I sensed her closeness to me, that she was mine, and each of us was nothing without the other—yet by some strange misunderstanding, leaving the theatre we would each time say farewell and separate like strangers. What people in the city said about us, God knows, but in all they said there was not one word of the truth.

In the following years Anna Alexeyevna began to go away more often to visit her mother or her sister; bad moods came over her, a sense that her life was wrong, tainted, and then she didn’t want to see either her husband or her children. She was by now receiving treatment for a nervous disorder.

We were silent, everyone was silent, but in the presence of strangers she experienced some odd irritation with me; whatever I spoke about she would disagree with me, and if I raised a question she would take the side of my opponent. When I dropped something she would say coldly, ‘Congratulations.’

If, having gone to the theatre with her, I forgot to take the opera glasses, she would say, ‘I knew you’d forget.’

Fortunately or unfortunately, nothing happens in our lives that doesn’t end sooner or later. The time of separation ensued, since Luganovich was appointed Chairman in one of the western provinces. They had to sell furniture, horses, the summer place. When they went out to the cottage and back, looked around for a final time, looked at the garden, the green roof, it was sad for everyone, and I remembered that the time had come to say goodbye, and not just to the cottage. It was decided that at the end of August we would see off Anna Alexeyevna to the Crimea, where her doctors were sending her, and a little later Luganovich would leave with the children for his western province.

We sent Anna Alexeyevna off in a great crowd. When she had said goodbye to her husband and children, and there remained only an instant before the third bell, I came running toward her in her compartment in order to set on a shelf something from her work basket that she had almost forgotten; and we had to say goodbye. When our glances met, there in the compartment, strength of mind abandoned us both, I held her in my arms, she pressed her face to my chest, and tears flowed from her eyes; I kissed her face, shoulders, hands, all wet with tears—oh how unhappy we were about it! I confessed my love for her, and with a burning pain in my heart I understood how superfluous and small and illusory everything was that prevented us from loving. I understood that when you love, when you ponder this love, you must proceed from something higher, of more importance than happiness or unhappiness, sin or virtue in the commonplace sense; or you shouldn’t think at all.

I kissed her for the last time, shook her hand, and we separated—forever. The train was already moving. I sat in the neighbouring compartment—it was empty—and until the first village I sat there and cried. Then I went on foot to my place at Sophina . . .”

While Alyokhin was telling his story the rain had ended, and the sun came out. Burkin and Ivan Ivanych went out on the balcony; from it, there was an attractive view of the garden and the stretch of river, which now shone in the sun like a mirror. They feasted their eyes and at that moment felt sorry that the man with kind, wise eyes who talked to them with such candour, who really did go round and round on this huge estate like a squirrel in a cage, wasn’t occupied with science or some such thing which would make his life more pleasant; and they thought how sad her face must have been, the young lady, when he said goodbye to her in that compartment and kissed her face and shoulders. Both of them had run across her in the city, and Burkin had already made her acquaintance and found her attractive.

—Anton Chekhov, Translated by David Helwig

/

/

I think Mr. Helwig is probably very humble about his abilities in his introduction. Having translated much Russian literature in college, and now having written (a little), I think his claim to a writer’s advantage in translation is more than salient and valid. A person fluent in the language can easily translate the words and yet have no feeling for the narrative at all. I’m certain I butchered a bunch of Turgenev, Gogol, etc., when I was extremely fluent and not yet a writer. I like Mr. Helwig’s fluid sentences, his language choices…lovely to read.

Concerning the ‘fluid’ sentences: in so far as possible in all the Chekhov translations I tried to keep to his syntax, even his punctuation.

What a treat. I am looking forward to reading more.

Seems to me, having only read one other translation of this story, that keeping to the original syntax and punctuation gives the story a great deal of freshness and honesty. Makes it feel alive somehow.

One thing I admire about translation is how, as a composite, all good translations keep a work alive, like different performances of the same piece of music.

I’m looking forward to reading more, too.

This is a fine translation, Mr. Helwig, and thank you for posting it here. I am glad to see that the liberation of Chekov (and other Russians) from the cold embrace of Constance Garnett goes on.