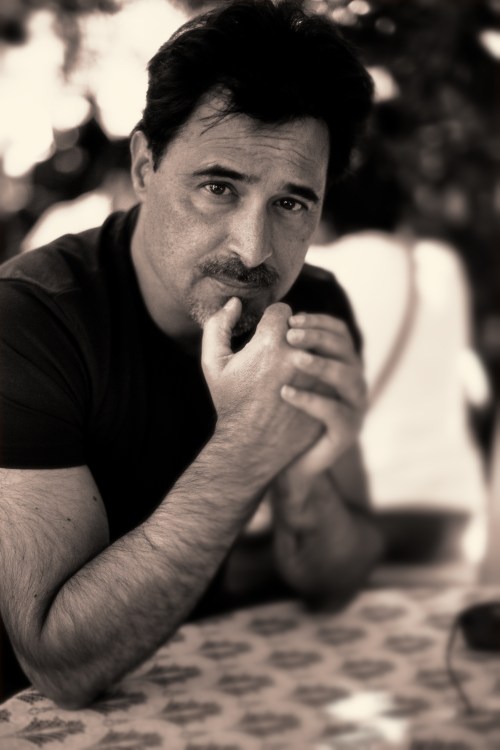

J.P. McEvoy portrait by James Montgomery Flagg, from a 1951 print

J.P. McEvoy portrait by James Montgomery Flagg, from a 1951 print

x

The 1920s saw a surge in experimentation with the form of the novel. In Ulysses (1922), James Joyce used a different style for each chapter, including the play format for the notorious Nighttown episode. Jean Toomer’s “composite novel” Cane (1923) consists of numerous vignettes alternating between prose, poetry, and drama. John Dos Passos in Manhattan Transfer (1925) abandoned traditional narrative for a collage of individual stories, newspaper clippings, song lyrics, and prose poems. Taking his cue from European Surrealists, Robert M. Coates likewise deployed newspaper clippings, along with footnotes, diagrams, and unusual typography, in The Eater of Darkness (1926). Djuna Barnes’s novel Ryder (1929) includes a variety of genres—poems, plays, parables—and is written in a pastiche of antique prose styles. William Faulkner scrambled chronology and used four distinct narrative voices in The Sound and the Fury (1929), and later even added a narrative appendix. These were all serious novelists who disrupted nineteenth-century narrative form to reflect the discontinuities, upheavals, and fragmentation of the early twentieth century, a time when many new media emerged that would rival and in some quarters supplant the novel in cultural importance and popularity.

But literary historians have overlooked a novelist from the same decade who deployed these same formal innovations largely for comic rather than serious effect, adapting avant-garde techniques for mainstream readers instead of the literati. Between 1928 and 1932, J. P. McEvoy published six ingenious novels that unfold solely by way of letters, telegrams, newspaper articles, ads, telephone transcriptions, scripts, playbills, greeting card verses, interoffice memos, legal documents, monologues, song lyrics, and radio broadcasts. Ted Gioia described Manhattan Transfer as a scrapbook, which could describe McEvoy’s novels as well, and in fact a reviewer of his first novel used that very term.[1] Given their concern with a variety of media (vaudeville, musicals, movies, newspapers, greeting cards, comic strips, radio) and their replication of the print forms of those media, they might better be described as multimedia novels. But perhaps the best, if anachronistic, category for McEvoy’s novels is avant-pop, that postmodern movement of the late 1980s/early 1990s which (per Brian McHale, quoting Larry McCaffery) “appropriates, recycles and repurposes the materials of popular mass-media culture, ‘combin[ing] Pop Art’s focus on consumer goods and mass media with the avant-garde’s spirit of subversion and emphasis on radical formal innovation.’”[2]

Since McEvoy is all but unknown, a brief biographical sketch follows.

An orphan, Joseph Patrick McEvoy told the Rockford Morning Star later in life that he didn’t “remember where he was born—but he has been told that it was New York City and that the year was 1894.” Newspaper comic historian Alex Jay, who records that remark in a well-researched profile,[3] gives a number of possible birthdates ranging from 1894 to 1897; the consensus today is 1895. Possibly born Joseph Hilliek or Hillick, the boy was adopted by Patrick and Mary Anne McEvoy of New Burnside, Illinois. The same Rockford Morning Star piece reports him as saying “he didn’t go to school—he was dragged. This went on for a number of years, during which time McEvoy grew stronger and stronger—until finally he couldn’t be dragged any more. This was officially called the end of his education.” In the contributors’ notes to a 1937 periodical, he wrote (in third person): “While he was still a guest in his mother’s house, J. P. McEvoy started his writing career at the age of fifteen as Sporting editor of the South Bend Sporting-Times.”[4] He later admitted (in first person), “I remember my first assignment as sports editor for the News-Times [sic] was to cover a baseball game. I was a descriptive writer. I became so interested in what was going on that I omitted the detail of scoring the game. I had to call The Tribune (a rival newspaper) to get the score.”[5] In 1910 he enrolled at the University of Notre Dame, which he attended until 1912.

In 1920, a stationery industry journal called Geyer’s Stationer gave this account of his early career (again from Jay):

It is interesting to take a peep into Mr. McEvoy’s past. He early acquired the art of hustling—perhaps that is why he is able now to do the work of two or three men. At Christian Brothers’ College in St. Louis he was the star bed maker. One hundred and fifty a day was his regular chore. Later, at Notre Dame University, he was a “waiter” at meal times and a newspaper man in the evenings. He worked on the South Bend News from six in the evening until two in the morning. When pay day came he required no guard to protect him—$4.00 constituted his salary!

When he came to Chicago, after graduating, he obtained a position as cub reporter in the sporting department of the old Record-Herald.

McEvoy in 1920 (l.) and 1922 (r.)

McEvoy in 1920 (l.) and 1922 (r.)

He created several comic strips there beginning in 1914, and moved on to the Chicago Tribune in 1916 for further strips before joining the P. F. Volland Company, which published books, postcards, and greeting cards. McEvoy published two illustrated books of sarcastic verse with Volland, both in 1919: Slams of Life: With Malice for All, and Charity Toward None, Assembled in Rhyme—with a postmodernish introduction in which McEvoy refers to himself in the third person as “his favorite author”—and The Sweet Dry and Dry; or, See America Thirst!, a mélange of poems and strips protesting the passing of the Eighteenth Amendment prohibiting the sale of alcohol. Slams of Life in particular trumpets the linguistic ingenuity that enlivens his later writings. The mostly comic poems are bursting with wordplay, slang, raffish rhymes, typographical tricks, and flamboyant diction: the first sesquipedalian word in one poem is “Absquatulating,” and the opening stanza of “The Song of the Movie Vamp” reads:

I am the Moving Picture Vamp, insidious and tropical,

The Lorelei of celluloid, the lure kaleidoscopical,

Calorific and sinuous, voluptuous and canicular,

And when it comes to picking pals, I ain’t a bit particular.

Many are quite literate, even erudite: “That’s a Gift” namedrops the historians Taine, Gibbon, and Grote, while another ranges from “the Ghibelline and Guelp” to “Eddie Poe.” The latter’s “The Raven” is parodied in “A Chicago Night’s Entertainment,” and “Lines to a Cafeteria or Glom-Shop” is a takeoff on a canto from “Kid” Byron’s Don Juan.[6] A poem with the baby-talk title “Bawp-Bawp-Bawp-Bawp-Pa!” acknowledges the ancient Greek orators “Who slung a mean syllable over the floor / Isaeus, Aeschines, Demosthenes, too,” and McEvoy seems to have been au courant with the latest poetry and art as well, for another one is entitled “An Imagist Would Call This ‘Pale Purple Question Descending a Staircase.’” He introduced Sinclair Lewis at a talk before the Booksellers’ League in Chicago in 1921; reporting the event, Publishers Weekly identified McElroy as the author of Psalms of Life, a sanctification of his Slams that probably amused him.[7]

McEvoy wasn’t happy at Volland, despite his lavish salary ($10,000 a year, equivalent to around $130K today) and the prestige of being “the first writer of greeting-card sentiments to be admitted to the Author’s League.”[8] In the author’s note at the end of his Denny and the Dumb Cluck—a 1930 novel satirizing the greeting-card business—he writes:

For many years I was editor and poet laureate of P. F. Volland and Co. and the Buzza Co., leaders in the manufacture and distribution of greeting cards, and among other minor atrocities I have compiled 47,888 variations of Merry Christmas. Also I have sat in on art conferences without number, where we met such important crises as “Shall we face the three camels east, or would it be better to put one of those Elizabethan singers out on the doorstep, holding a roll of wall paper?”

Until he resigned from Volland in 1922, McEvoy continued to write for the Chicago Tribune. It ran a serial called The Potters in 1921, illustrated by a friend he had made at Notre Dame named John H. Striebel (1891–1962), with whom he would later collaborate. The Potters was described as “a new weekly humorous satire in verse on married life in a big city” and was later turned into a successful play and published in book form in 1924.

By then McEvoy had left Chicago and was living in New York City, leaving behind both greeting cards and comic strips to write for the stage. First he wrote a revue called The Comic Supplement (1924), which was produced by Florenz Ziegfeld and starred W. C. Fields.[9] McEvoy wrote the original “Drug Store” sketch, one of Field’s favorites and reprised in some of his later films. Ziegfeld forced unwanted changes on McEvoy’s script, but later repented and invited him to begin writing for the Ziegfeld Follies. McEvoy cowrote the 1925 production (with Fields, Will Rogers, Gus Weinberg, and Gene Buck), and continued to contribute skits and songs until 1926.

In 1926 he wrote a two-act revue entitled Americana,[10] a smart but zany show that Gershwin biographer Howard Pollack describes in terms that anticipate McEvoy’s novels: “Americana . . . satirized American life, including an after-dinner speech at a Rotary Club and an awkward attempt by a father to talk to his son about sex; it also took aim at opera (‘Cavalier Americana’) as well as Shakespeare by way of [composer Sigmund] Romberg (‘The Student Prince of Denmark’). Critics welcomed the show as refreshingly clever—a ‘revue of ideas,’ as the Times headline stated. . . .”[11] His other revues—No Foolin’ (1926), Allez Oop (1927), and New Americana (1932)—were less successful but provided plenty of backstage material for his novels.

It was at the Ziegfeld Follies that McEvoy met the inspiration for his first novel. Louise Brooks (1906–1985) was a featured dancer in the 1925 edition, and caught the eye of Paramount Pictures producer Walter Wanger, who signed her to a five-year contract later that year. McEvoy thought the wild-living Brooks would make an attractive heroine for a comic novel, and after naming her “Dixie Dugan” began writing a fictional account of her madcap adventures in show biz. Show Girl—made up of letters, telegrams, newspaper clippings, and so forth—was serialized in Liberty Magazine from 14 January to 14 July 1928, illustrated by his Notre Dame classmate John Striebel, who modeled Dixie on Brooks.

John Striebel illustration, Liberty serialization of Show Girl

John Striebel illustration, Liberty serialization of Show Girl

It was published in book form by Simon & Schuster in July of the same year, and was an immediate success, going through five printings in two months for a total of 31,000 copies in print—not to mention reprints by two other publishers, two British editions, and a German translation (Revue-Girl, adapted by Arthur Rundt). Show Girl deals with Dixie’s zigzagging path to success on Broadway; in its sequel, Hollywood Girl, Dixie (like Louise Brooks) travels out to Hollywood for further risqué adventures. Like its predecessor, Hollywood Girl was first serialized in Liberty (22 June–28 September 1929), then published by Simon & Schuster in book form later in 1929. Both were quickly made into movies, Show Girl (1928) and Show Girl in Hollywood (1930); it was initially reported that Brooks would play Dixie, but she didn’t get the part, possibly because she was under contract to another studio (though she had been loaned out before). Both films starred Alice White instead, who resembled It girl Clara Bow rather than the vampy Brooks. Stills from the films were tipped into later printings of both novels, an early example of media synergy.

In 1929, McEvoy’s former employer Florenz Ziegfeld, who appears as a character in Show Girl, produced a musical entitled Glorifying the American Girl with a script cowritten by McEvoy, and then staged a musical version of the novel, on which Gershwin again collaborated.[12] The lamest but longest-lasting spin-off of Show Girl is the comic strip Dixie Dugan, which McEvoy and Striebel began in October 1929 and which ran until October 1966, long after both had died.[13] The show-biz premise was soon dropped for a series of light romantic adventures, and today the strip is held in low esteem by most comic book historians. As Jay notes, McEvoy appeared in the 17 October 1939 edition of the strip, metafictionally depicted arguing with Dixie over money made from the franchise. A forgotten movie version, also called Dixie Dugan and starring Lois Andrews, was released in 1943.

McEvoy in Dixie Dugan comic strip

McEvoy in Dixie Dugan comic strip

Later Dixie Dugan strip

Later Dixie Dugan strip

McEvoy followed Hollywood Girl with four more novels in the same multimedia format. Denny and the Dumb Cluck (Simon & Schuster, 1930), is about a greeting-card salesman named Denny Kerrigan, who was first introduced in Show Girl as a long-distance love interest of Dixie’s. (The “dumb cluck” of the title is Denny’s new girlfriend, Doris Miller.) In the same author’s note quoted earlier, McEvoy admits

The truth is Denny and The Dumb Cluck is a grudge book. It was I who originated the most famous Christmas Greeting of all—Wishing you and yours a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year. You have probably used it yourself, not knowing—nor caring, which is worse—that it was stolen from me, that I have not received one cent of royalties for it.

I was robbed of that beautiful sediment [sic: a pun often used in his novels] and I swore that I would bide my time and some day I would get even. Denny and The Dumb Cluck is my answer.

McEvoy’s fourth novel, a satire of the comic-strip business entitled Mr. Noodle: An Extravaganza, was serialized in the Saturday Evening Post from 15 November to 20 December 1930 (a little too elegantly illustrated by Arthur William Brown) and published in book form by Simon & Schuster in April 1931. In the fall of that year they also published Society—serialized as Show Girl in Society in Liberty between 30 May and 8 August, again illustrated by Striebel—which picks up the Dixie Dugan story where it left off at the end of Hollywood Girl and, after a satiric view of high society in both Europe and the U.S., brings her zany story to an end.

John Striebel illustration, Liberty serialization “Show Girl in Society”

John Striebel illustration, Liberty serialization “Show Girl in Society”

McEvoy’s final novel, Are You Listening?, was serialized in Collier’s Weekly between 17 October and 12 December 1931 (illustrated by Harry L. Timmins) and quickly made into a movie with the same title before it was published in book form by Houghton Mifflin in August of 1932. McEvoy’s last two novels apparently didn’t sell well, for they are nearly impossible to find today.

In 1930, at the height of McEvoy’s success, Broadway columnist Sidney Skolsky ticked off some amusing if questionable trivia about him:

His first piece of writing appeared in the South Bend News. He inserted a job-wanted advertisement.

For some unknown reason he is afraid to enter a laundry.[14]

Lives at Woodstock, N. Y. Is the proud possessor of two blessed events and a St. Bernard dog. The two children are now attending school in California. The dog, dying of loneliness, is to be shipped there next week.

The only jewelry he wears is a black opal ring. Wears this because everyone says it is unlucky.

Is very fond of people who resemble him.

He saves unused return postal cards.

Never actually writes a play or story. He dictates everything. Always has two secretaries working. Never revises any of his manuscripts. Show Girl has fourteen chapters. It was dictated at fourteen settings.

He is unable to part his hair.

Believes there should be a law against bed makers who never tuck in the sheets at the foot of the bed.

As far as comedians go he starts laughing if he’s in the same city as Jimmy Durante.

Always buys two copies of a book. One to read and one to lend.

His full name is Joseph Patrick McEvoy. His mother named him Joseph. His father named him Patrick. Not caring for either, he became J. P. McEvoy.

He has a picture of his wife in every room.

Still receives royalties on some of the greeting cards he wrote. His favorite is the following:

Eve had no Xmas

Neither did Adam.

Never had socks,

Nobody had ’em.

Never got cards,

Nobody did.

Take this and have it

On Adam, old kid.

He was once an amateur wrestler. Gave it up because he didn’t like being on the floor.

He hates to see people in wet bathing suits.

His first book to be published was a volume of poetry titled Slams of Life. He has the names of those who bought it. Two more sales and he could have formed a club.

Smokes a cigar from the moment he turns off the shower in the morning until he puts on his pajamas at night.

His pet aversions are women’s elbows, chocolate candy all melted together, fishing stories, fishermen, fish, Laugh, Clown, Laugh; radio talks on how to make hens lay, buying new shoes, mixed quartets, Laugh, Clown, Laugh; runs in silk stockings, three-piece orchestras, waiters who breathe down his neck and Laugh, Clown, Laugh.

When in New York he puts up at the Algonquin. If working on a story or play he and his wife occupy separate rooms.

His first writing for the stage was a vaudeville sketch. Out of the Dark, written with John V. A. Weaver. It played only two performances in a four-a-day vaudeville house.

His favorite composers are Tchaikovsky, and George Gershwin. His favorite conductors are Toscanini and Frank Kennedy of the Fifth Avenue bus line.

Has two mottoes. One for the home and one for the office. The motto hanging in his house is: “Let No Guilty Dollar Escape.” The motto hanging in his office is: “Watch Your Hat and Coat.”

Dislikes all the Hungarian Rhapsodies from number one to twelve.

His idea of a grand time is hearing Paul Robeson sing anything, going to Havana, being petted by any brunette not over five feet five, depositing royalty checks from Simon & Schuster, throwing pebbles into a lake, reading anything by James Stephens, eating kalteraufschnitt mit kartoffelsalat and attending a Chinese theater with a Chinaman.

He once got sick eating a sandwich that was named after him.

After he quit running a column in the Chicago Tribune the circulation of the Tribune dropped from forty thousand to a million.[15]

McEvoy continued to work in movies and publishing throughout the 1930s and 1940s. He appears in the opening credits of the 1933 film The Woman Accused as one of the ten authors who wrote a chapter each of the serialized novella (in Liberty) from which the screenplay was adapted; he collaborated again with W. C. Fields on the latter’s 1934 films You’re Telling Me! and It’s a Gift; wrote nonfiction accounts of his life in upper New York State; published a children’s book called The Bam Bam Clock (Algonquin Publishing Co., illustrated by Johnny Gruelle); and he wrote a humorous advice column called “Father Meets Son” for the Saturday Evening Post (published in book form by Lippincott in 1937).

McEvoy with W.C. Fields at a Paramount banquet, 1934

McEvoy with W.C. Fields at a Paramount banquet, 1934

He coauthored the screenplay for Shirley Temple’s musical Just around the Corner (1938), along with an article on her (“Little Miss Miracle”) in the 9 July 1938 issue of the Saturday Evening Post, which reproduces a photograph of the author sitting next to the ten-year-old actress. He wrote the book for Stars in Your Eyes, a 1939 Broadway revue starring Ethel Merman and Jimmy Durante (the latter had a cameo in McEvoy’s first novel). Other notable magazine contributions include an interview with Clark Gable about Gone with the Wind in the 4 May 1940 issue of the Saturday Evening Post (there’s a photo available of a tuxedoed McEvoy dancing with Gable’s co-star Vivien Leigh), and a profile of Walter Howey, editor of William Randolph Hearst’s Boston American, in the June 1948 issue of Cosmopolitan. He was famous enough to be featured in magazine ads for White Owl cigars, “just off the plane from Havana” (reproduced by Jay).

McEvoy with Shirley Temple, 1938

McEvoy with Shirley Temple, 1938

McEvoy dancing with Vivien Leigh, 1939

McEvoy dancing with Vivien Leigh, 1939

McEvoy in White Owl cigar ad, 1940

McEvoy in White Owl cigar ad, 1940

McEvoy spent the rest of his life contributing to Reader’s Digest as a roving editor, travelling with his third wife, and entertaining a veritable who’s who in America. Visitors to his large estate near Woodstock included members of the Algonquin Round Table, Frank Lloyd Wright, Clarence Darrow, Rube Goldberg, and avant-garde composer George Antheil. “One hectic weekend,” a local newspaper reported (per Jay), “almost the entire membership of the American Society of Artists and Illustrators attended a fabulous weekend party.” In 1956, McEvoy published his last book, Charlie Would Have Loved This (Duell, Sloan and Pearce), a collection of humorous articles. He died on 8 August 1958.

x

“Get hot!”: The Dixie Dugan Trilogy

For most readers in 1928, Show Girl looked utterly unlike any novel they had ever seen. Preceding the title page is a teaser with some hype from the publisher’s Inner Sanctum imprint,[16] and the title page itself is an elaborate cast list “In the order of their appearance,” as in a theater program or the opening credits of a silent film. Each “performer” is followed by a saucy descriptive line, beginning with “Dixie Dugan: The hottest little wench that ever shook a scanty at a tired businessman.” The novel proper begins with a dozen pages of letters—familiar enough from epistolary fiction—which are quickly followed by a cavalcade of telegrams, Western Union cablegrams, newspaper articles (in two columns and a different font) and letters to the editor, playlets in script form, police reports (IN SMALL CAPS), poems and greeting card verses, a detective agency log, various theater materials (ads, reviews, notices, house receipts), one-sided telephone conversations, a dramatization of a business convention, radiograms, even a House of Representatives session reprinted from the Congressional Record.

Title page for Show Girl

Title page for Show Girl

All of this narrative razzmatazz supports a screwball-comic Broadway success story that occurs over a six-month period in 1927. (Nearly every document is dated, from May 1st to October 22nd.) The first half of the novel tracks Dixie’s hectic rise to notoriety. As this 18-year-old Brooklynite explains in a letter to her long-distance boyfriend Denny Kerrigan, she’s hell-bent on joining the chorus line of the Ziegfeld Follies.[17] He, on the other hand, writes that he wants to “get married and get a little apartment in Chicago, and I’ll come home to you every Saturday night after my week on the road selling mottoes and greeting cards in Indiana” (98).[18] Failing her Ziegfeld audition, Dixie instead becomes a specialty dancer at the Jollity Night Club, where she attracts the smoldering glances of “a tall, dark-haired, black-eyed tango dancer” named Alvarez Romano, who turns out to be the son of a South American president. (She enjoys making out with him: “And when he kisses—well the kid goes sorta faint and dreamy and don’t care-ish and can barely get through the front door and slam it shut” [19].) She also attracts the attention of a 45-year-old Wall Street broker named Jack Milton,[19] who one night after the show invites Dixie and other dancers to a party with his Wall Street buddies. He gropes and mauls her, only to be interrupted by Romano, who stabs him.

The New York Evening Tab turns it into a salacious scandal, and as a result Dixie is deluged with job offers, endorsement deals, and marriage proposals. The Evening Tab begins running Dixie’s first-person life story, ghostwritten and completely fabricated by reporter Jimmy Doyle, whom Dixie describes as “cute as a little red wagon and writes beautiful and I think he’s hot dog” (98). Fairly literate (though he confuses Swinburne with Browning), he describes his “bogus autobiography” to a Hollywood friend as follows, in a representative example of McEvoy’s jazzy style and his contempt for tabloid readers:

Well, I’m still Dixie Dugan and my contribution to the Fine Arts is monastically entitled “Ten Thousand Sweet Legs.” Boy, it’s hot. With one hand I offer them sex and with the other I rap them smartly over the knuckles with a brass ruler and say “Mustn’t touch. Burn-y, burn-y.” Then I sling them a paragraph of old time religion and single standard and what will become of this young generation. (I hope nothing ever becomes of it. I like it just the way it is.) And then another paragraph like the proverbial flannel undershirt that is supposed to make you hot and drive you crazy, and presto! the uplifted forefinger, “But this is not what you should be interested in, children.” And then a little Weltschmerz and then the old Sturm und Drang—a Sturm to the nose followed up with a Drang to the chin—the old one-two. So, as you may gather, this opus is the kind of love child that might result from an Atlantic City week-end party with the American Mercury and True Stories[20] occupying adjoining rooms. So much for literature! (77–78)

Spying on Dixie one night outside the theatre of her new show, Jimmy sees Romano abduct Dixie (to take her back to “Costaragua” to marry her), abducts Dixie himself when their limousine crashes, and then convinces her to lay low while his newspaper milks her disappearance for weeks. The recovering Jack Milton hires detectives to find her, offers to underwrite a musical for Dixie, and enlists Jack to write the book and lyrics for it.

Pages from Show Girl

Pages from Show Girl

The second half of the novel documents the progress of the musical from its contentious beginning—Milton hires show-biz producers who rewrite Jack’s script and bring in outside contributors[21]—to its disastrous out-of-town opening, to its eventual success after Jack takes charge and restores his original conception. Retitled Get Your Girl, the musical makes Dixie a star, and Jimmy realizes he loves Dixie as much as she does him: “Besides being cute and all that she’s got a quick mind, a keen sense of humor and says just what she thinks,” he writes to his Hollywood friend. “And she really thinks” (195). Meanwhile, Dixie’s three suitors come to different ends: she rejects the marriage proposal of her sugar daddy, Jack Milton. Denny Kerrigan, still pining for Dixie, makes a big splash at a greeting-card convention in Atlantic City (where he catches Dixie’s show), and heads home with a promotion if not with the girl. On a darker note, Alvarez Romano returns to Costaragua to help his father lead a counter-revolution, is captured, and sentenced to death. He escapes, but all his fellow prisoners are slaughtered, as a two-page article from the Evening Tab reports in gruesome detail. McEvoy places that tragedy near but not at the conclusion of the novel in order not to spoil the happy ending: Dixie finds success and love, conveyed by some clever parodies of notable theater critics of the day (Percy Hammond, Alexander Woollcott, Alan Dale, Walter Winchell) and a flurry of giddy radiograms.

Aside from the novelty of its format, the most appealing aspect of Show Girl is its language. Often sounding like a risqué and snarky P. G. Wodehouse, McEvoy offers a fruity cocktail of slang and flapperspeak, most of it from Dixie herself. She slings words and phrases such as “into the merry-merry” (show biz), “a good skate” vs. “a wet smack” (a fun vs. dull person), “gazelles” and “gorillas” (young women and nightclub predators), “butter and eggers” (theater audiences), “ginny” (tipsy), “static” (unwanted advice), “goopher dust” (a legal loophole), “blue baby” (a dud play), “clucks” (dumb people), “crazy as a brass drummer,” and exclamations like “Tie that one,” “skillabootch,” and “Get hot!” (encouragement shouted at a good dancer). Glib Jimmy Doyle has already been quoted, and throughout McEvoy inserts some clever song lyrics, parodies, and greeting-card verse; he even has Denny quote and praise a song from his own musical Allez Oop. There are times when the insider theater lingo becomes hermetic (“the old comedy mule stunt . . . an easy hit in the deuce spot . . . an unsubtle comedy team in ‘one’ with Yid humor and soprano straight . . . novelty perch turn in four . . . the choice groove next to shut” [52]), but all the slang and shoptalk is a constant delight. One reviewer said “Five years from now Show Girl and Hollywood Girl will need a glossary.”[22] Dixie agrees: she starts a diary in the latter for the benefit of her future biographers:

I can refer them to you Diary and they can see for themselves I’m not handing them a lot of horsefeathers. I suppose too Diary we should keep posterity in mind because when they came across a word like horsefeathers and didn’t know what it meant we should have it defined somewhere, so for the sake of posterity horsefeathers means a lot of cha-cha and cha-cha means what diaries are usually full of. (Hollywood Girl 35)

Dixie is the first of many independent, untraditional young women in McEvoy’s novels. She is a self-proclaimed representative of “flaming youth” (a 1923 novel and silent movie), and at times sounds surprisingly 21st-century: “The real ambition of our young generation . . . is to be cool but look hot” (7). At a time when most young woman wanted to get married as soon as possible, Dixie tells Denny, “I don’t want to marry you or anybody else. . . . I’m young and full of the devil and want to stay that way for a while” (94)—a sentiment that will be voiced by many of McEvoy’s young heroines.

Pages from Show Girl

Pages from Show Girl

In Show Girl McEvoy introduces other themes that will run through all of his novels, dark undercurrents beneath their playful surfaces. His contempt for the general public has already been noted in Jimmy’s condescending remarks on his newspaper readers, an attitude that McEvoy will later extend to theater audiences, greeting-card customers, comic-strip fans, and radio listeners. When Jimmy meets with the Broadway producers who want to dumb down his play, we get this exchange:

DOYLE (bitterly): I suppose if you got “Romeo and Juliet” you wouldn’t produce it unless you could buy a balcony cheap.

EPPUS: “Romeo and Juliet”? Pfui! I seen that once. There wasn’t a hundred dollars in the house.

KIBBITZER: That kind of play don’t make money. You got to stick to things people understand. (112–13)

Kibbitzer later makes a pass at Dixie, and sexual predation in show business is another recurring theme. Dixie breezily dismisses that incident—“Well, that’s what a female gets for having Deese, Dem and Doze” (118)—but along with her earlier sexual assault at Jack Milton’s party and the lascivious advances of club “gorillas,” McEvoy dramatizes how dangerous show biz is for “gazelles” like her.

The mendacity of the media is mostly played for laughs here, with the joke on the dumb clucks who take celebrity gossip as gospel and actually believe the “sediments” expressed in greeting cards, but corruption is handled more seriously. When the police arrive at Milton’s wild party and arrest Alvarez, Dixie notes that one of the guests, “Wilkins his name was, a big politician I found out later—got the cops off to one corner and gave them some sort of song and dance” that keeps their names out of the papers the next day (30, 32). Near the end, Alvarez’s father travels to New York and promises Milton the oil concession in Costaragua in exchange for financing his revolt; Milton gets a few of his Wall Street pals together and decide “that would be the patriotic thing American thing to do. Our country may she always be right,” Dixie remembers him saying, “but right or wrong we’ve got to have oil.” Milton enlists an Alabama congressman named Fibbledibber to convince his fellow representatives via patriotic rhetoric that America’s honor depends upon &c &c &c, and sure enough Congress authorizes the Marines to intervene in the South American country. These darker elements add depths to what would otherwise be a light entertainment—depths that were drained by the producers of the 1928 movie version (no doubt of the same mindset as Kibbitzer & Eppus), according to those who have seen it. The novel is dark and daring, like Louise Brooks; the movie is blonde and harmless, like Alice White.

Alice White in 1928 movie version of Show Girl

Alice White in 1928 movie version of Show Girl

Show Girl’s reviews were as boffo as those for Dixie’s performance in Get Your Girl. Marian Storm quite rightly praised it as “a show-case of language. Whirling, whizzing, dizzying—a bombardment upon eye and ear of monotonous, accurate, faithful ugliness, of snappy similes.” Proposing a new criteria for literature, the Springfield Republican said, “If making ‘whoopee’ is one of the aims of literary art, Mr. McEvoy has scored a literary success.” Ziegfeld himself reviewed it for the Saturday Review of Literature—despite appearing in Show Girl as a character!—and described it as “show business ‘hoked up’ to the saturation point. . . . The action races by and every typographical ingenuity is used to emphasize and amplify the ‘punch stuff’”—slinging slang as deftly as Dixie, but perhaps not entirely comfortable with seeing his profession mocked.[23]

***

Published a little over a year later, Hollywood Girl is one of the first and still best satires of Hollywood—a clichéd subject today but a novelty in 1929, when the industry was still young and making the transition from silent films to talkies. It begins seven months after the conclusion of Show Girl, and ends a year later (i.e., May 1928–April 1929), and features a similar story arc. Get Your Girl having run its course, Dixie is back in Brooklyn looking for work while Jimmy tries to write a new star vehicle for her, vowing to marry Dixie as soon as it is staged. When Dixie learns that flamboyant movie director Fritz Buelow[24] is in New York casting his next epic—Sinning Lovers, based on “The Charge of the Light Brigade”[25]—and is “hot for a jazz-mad baby that could make yip yip and faw down in a new squeakie,” as Dixie puts it (14), she finagles an interview and passes a screen test, on the basis of which she’s given a tentative contract and sent to Hollywood. She gets only bit parts at first, and then none at all, and learns the studio will not be renewing her contract.

At this low point, nearly halfway through the novel, Dixie delivers an emotional, 18-page interior monologue modeled on Molly Bloom’s at the end of Ulysses, at the end of which Jimmy calls her and vows to help. (He too is now in Hollywood as a screenwriter.) He feels a publicity party is what she needs to attract work, which results in a remarkable chapter entitled “Hollywood Party: A Talking, Singing, Dancing Picture with Sound Effects,” another 18-page tour de force that ends with the suicide of an “aging” actress. (“I’m thirty two,” she tells Dixie, “and in this business if you’re [a woman] over thirty you’re older than God” [124].) While the party rages, Dixie goes off with Buelow to another party and is nearly raped. All this Sturm und Drang is heightened by troubling rumors that a Wall Street syndicate of bankers, including Dixie’s old admirer Jack Milton, will be merging the major studios, eliminating jobs, and moving the whole business back east.

Pages from Hollywood Girl

Pages from Hollywood Girl

At about the same structural point in Show Girl where Jack regains control of his musical, Dixie learns she has been given the lead in Sinning Lovers, once again thanks to Jack Milton. (Ironically, the studio had decided to give the role to the aging actress the same night she committed suicide.) Dixie is tempted to accept Milton’s marriage proposal after she and Jimmy have the last in a series of fights, but after the preview version of the movie flops, she drops him because he wants to give up on the film (and on her career). She is shocked at his philistine views: “Jack says so far as the bankers are concerned if it doesn’t make money it’s not a good picture and I says what about Caligari[26] and he says I never saw it and from all I’ve heard of it I never want to see it . . .” (205). Fortunately, another producer and director step in, save the film (retitled Loving Sinners under pressure from the censorious Hays office), and the movie makes Dixie a star, as attested by another raft of rave notices (more real-life reviewers, this time representing Los Angeles).

But this is where the novel takes a surprising turn. Unexpectedly, Jimmy Doyle is not called in to save the screenplay, make up with Dixie, and marry her at the end. Instead McEvoy lets fame and riches go to her head: Dixie starts hanging out with silly rich people, indulges in trivial pursuits, and only two weeks after meeting Teddy Page, a “New York millionaire sportsman and young society aviation enthusiast” (227), she elopes with him in Las Vegas. She’s aware he’s a binge-drinking, hell-raising skirt-chaser, but she’s convinced she can change him. “It’s only because he hasn’t met the right kind of girl” (235). (Cue reader’s rolling eyes.) The penultimate page of the novel features a tipped-in wedding photo of the couple (with a dead ringer for Louise Brooks as Dixie), followed by an announcement in the New York Times that Page’s wealthy family has cut ties with him.[27] This unexpected ending is a daring subversion of the wedding bells convention typical of most romantic books and movies, but Hollywood Girl is not a typical novel.

Final pages of Hollywood Girl

Final pages of Hollywood Girl

Final pages of Hollywood Girl, Liberty serialization

Final pages of Hollywood Girl, Liberty serialization

In addition to all the narrative bells and whistles of Show Girl, the sequel sports a publicity release, cast lists and shooting schedules, the morality clause from an actor’s contract, interoffice memos, six drafts of the opening sentences of a letter, screenplays (complete with camera directions), a full-page ad in Variety, and some unpunctuated, modernist-looking dialogue. Plus there’s a parody of Edgar Guest (reminiscent of the poems in The Sweet Dry and Dry) and that Joycean monologue. Dixie starts and abandons a diary, which feels like a narrative crutch on McEvoy’s part, but Dixie is so entertaining that it would be churlish to complain. There’s another slew of slang: “maddizell,” “laying down a few flat arches” (dancing), “belchers” (talking pictures), “dog house” (a bass violin), “sitzplatz” (sitting place=ass), and “Hot cat!” (expressing excitement). Jimmy is as glib as ever, as when he is asked by a reporter for his first impression of Hollywood: “Offhand, it looks a little bit like Keokuk [in Iowa] on a Sunday afternoon, except that the houses and vegetation seem to have been retouched by one of those disappointed virgins who go in for painting china” (67). But he can’t top Dixie on the difference between the Big Apple and the Windy City: “New York is a jazz-band playing diga-diga-doo but Chicago is just a big megaphone with an overgrown boy hollering through it: Look at me, ain’t I big for my age” (40).

Like the first novel, there are a few celebrity cameos, including Dixie’s counterparts Louise Brooks and Alice White, aptly enough, and Aimee Semple McPherson via the radio airwaves. Von Stroheim is seen working with Gloria Swanson on Queen Kelly, a production as costly and strife-ridden as Sinning Lovers, and fans of old Hollywood will revel in all the namedropping, tech talk (UFA angles, lap dissolves), and insider dope.

Sexual predation is even more prominent here than in McEvoy’s first novel, and creepier: Show Girl is PG-13, Hollywood Girl R-rated. Director Buelow is a letch who indulges in Trump/Bush “locker room banter” and seduces the Evening Tab reporter who interviews him near the beginning of the novel (and who begins dating Jimmy at the end, when he returns to his job there), and plans to do the same with Dixie. (First, she has to fend off his manager with a joke about pedophilia.) Warned by Jimmy that Buelow “was on the make for me,” Dixie tells her diary “of course he’s on the make and what of it, all men are, only some are sneaky and don’t admit it . . .” (42). Jimmy tells her she will have to put out to be put in Buelow’s movie, which causes their first spat, but Dixie sees plenty of that after she’s been in Hollywood a few months. She keeps saying no to all the men who hit on her, including Jimmy’s Hollywood correspondent, unlike those who say yes: “that’s how you get along say yes talk about yes-men you never hear of the yes-girls but they’re the ones with the Minerva cars and three kinds of fur coats I guess I could get there too if I said yes . . .” (81).[28] The novel is frank about the sex appeal of movies. The aging star says of the latest starlets,

they’ve got one thing I haven’t got—youth. They’ve got young necks and young legs and young eyes. And nice slim, soft young bodies. And you can’t fool the camera when it comes to those things. And that’s what they want out here in this business. Youth. Young flesh. And they feed it into the machine and out comes thousands of feet of young eyes and young legs and young bodies. Reels and reels of it. And that’s what people want to see. Men go there and watch them hungrily all evening and then go home and close their eyes when they kiss their wives. (124)

McEvoy would have used a different verb if he thought he could get away with it. A month later Dixie is almost raped by Buelow, and after her success she speaks of budding actresses in terms of prostitution:

Hardfaced mothers from all over the country dragging their little girls around to studios ready to sell them out to anyone from an assistant director to a property man just to make a little money off them. Agents with young girls tied up under long term contracts at a hundred a week leasing them to studios for ten times that and pocketing the difference. Hundreds of pretty kids from small towns, nice family girls, church girls, even society pets going broke and desperate, waiting tables, selling notions, peddling box lunches on the street corners—I could tell you stories that would curl your hair. (223–24)

Passages like this are what make Hollywood Girl closer in tone and intent to Caligari than Singin’ in the Rain.

These intimations on immorality in show biz perhaps account for the curious number of biblical allusions in the novel, beginning on the first page, when Dixie blithely answers an imaginary interlocutor: “Where’ve you been? On Broadway, sez I. Where on Broadway, sez you. Up and down, sez I—up and down, between Forty-eighth and Forty-second, looking for a job”—the final word punning on the source of Dixie’s diction, Job 1:7: “And the Lord said unto Satan, Whence comest thou? Then Satan answered the Lord, and said, From going to and fro in the earth, and from walking up and down in it.” Over the next few pages there are allusions to the twelve apostles, Jonah and the whale, the book of Genesis, Noah’s ark, and the Four Horseman of the Apocalypse. Though based on Tennyson’s poem, Sinning Lovers inexplicably begins with the Garden of Eden (with Dixie in Eve’s role), and when Dixie resignedly decides to marry Milton, she says, “sometimes I feel like that bimbo in the Bible who sold out for a mess of pottage” (cf. Gen. 25:29–34; “bimbo” is used of men and women in the novel).

Page from Hollywood Girl, Liberty serialization

Page from Hollywood Girl, Liberty serialization

The most sustained biblical allusion is the radio broadcast Dixie and Jimmy endure while in a restaurant: from L.A.’s Angelus Temple Aimee Semple McPherson delivers a hokey sermon on Daniel in the lion’s den, spread over four pages in small caps (174–77), exhorting her listeners to tune out “all the jazz bands and the frivolous things of this world” and to sing along with her (to the tune of “Yes Sir, She’s My Baby”):

Yes sir here’s salvation

No sir don’t mean maybe

Yes sir here’s salvation now

Goodbye sin and sorrow

Welcome bright tomorrow

For we’ve got salvation now (177)

This is too ludicrous to take seriously, and though Dixie occasionally refers to herself in terms such as “a devil on wheels” (231), she is hardly Satan, much less Eve, Esau, or Daniel, and her thoughtless elopement at the end makes a mockery of finding salvation. Nor is McEvoy calling for readers to renounce “the frivolous things of this world” like Broadway musicals and Hollywood epics; for his purposes, the Bible is no longer a moral guidebook but a source of wisecracks, but the recurring biblical references add one more unexpected level to the novel.

As with Show Girl, the reviewers ignored the dark depths and stayed at the bright surface of the novel, which they found a little dimmer than its predecessor. “The book is amusing, filled with Hollywood madness and Hollywood slang,” said the New York Times, “but it lacks the easy, hilarious fun of ‘Show Girl,’”[29] not considering the possibility that McEvoy was aiming at something more than “easy, hilarious fun.”

***

Two years later, McEvoy concluded Dixie’s sassy saga with Society, which picks up the same day Hollywood Girl left off.[30] The first half of the novel documents the first few months of Dixie and Teddy’s impulsive marriage: honeymooning down in Mexico and then up in Monterey, Teddy continues drinking and chasing after women, which soon drives Dixie to Hollywood to resume her career. But they make up, and Dixie begins learning more of Teddy’s rich family: his 18-year-old sister Serena, whom he calls “a wet smack and dumb as a duck” (6), who is preparing to make her debutante debut that fall; his 16-year-old sister Patricia, a hellion already wearing heels who has seen Dixie’s film and runs away from private school to pursue a similar career in Hollywood; and Teddy’s predictably stuffy mother and father; in order to trace his daughter, the latter hires the same Open Eye Detective Agency that searched for Dixie in Show Girl. Mr. and Mrs. Teddy Page, as they are called—Dixie loses much of her independent identity after she marries: “Teddy is my career now” (42)—then sail to France to continue their honeymoon, but during the crossing Teddy lusts after an Apache dancer called Le Megot—“cigarette butt or a snipe,” as Dixie translates, and described as “one of the sexiest little devils I ever saw with a wild shock of hair, a slim lazy body, big black eyes and a red mouth that must drive men crazy” (70). Upon arrival in France, Dixie sends a telegram wittily announcing “LAFAYETTE I AM HERE” (74), but no sooner is the honeymooning couple settled in Paris than Teddy sneaks off to London “on business” to catch Le Megot’s act at the Kit Kat Club. Meanwhile, Dixie is escorted around Paris by an Italian gigolo who had tried to seduce her during the ocean crossing. After another big fight—Dixie throws “a complete set of Victor Hugo at [Teddy], all of which he managed to dodge with the exception of Volume II of ‘Les Miserables’” (109)—they make up and head down to the Riviera.

At that point, halfway through novel, the plot takes a metafictional turn: we learn that Jimmy Doyle is in Paris, working for Colossal Pictures again and “gathering material for a high society movie” (105–6). Excited to learn that Dixie is also in France, he telegraphs his producer with a revised idea: “COULD COMBINE EUROPEAN ANGLE SOCIETY AND DIXIES POPULARITY” (108, sic)—which sounds like a note McEvoy made to himself after finishing Hollywood Girl. Dixie continues to party with the idle rich and tells Jimmy she’s having fun, or “fun in a way. But it’s no pleasure—if you know what I mean. We’re all so bored—Teddy’s friends and their friends—and they work so hard to be amused—and nothing really makes ’em really laugh—only when they’re full of champagne and are their real selves but don’t know it” (123). Dixie is excited to learn she’s pregnant, but just then Teddy gets involved in a sex scandal and both have to sneak back to New York. As the Page family prepares for Serena’s obscenely expensive coming out ball at the Ritz-Carleton on Thanksgiving Eve ($50K, around $750K today), Patricia reconnects with the young communist radical she had met while en route to Hollywood, and attends a rally in Bryant Park at which he speaks the night of Serena’s ball. Learning the cost of the ball, her Red beloved leads a protest march to the Ritz, which is broken up by the police—or as the headline in the communist Daily Worker puts it (177):

TAMMANY COSSACKS DEFEND SACRED RITZ

FROM CONTAMINATION BY STARVING WORKERS

THOUSANDS OF DOLLARS FOR ORCHIDS

WHILE MILLIONS CRY FOR BREAD.

Early the next year, Jimmy returns from France, manuscript completed, and tracks Dixie down in Palm Beach, where she is drinking to excess, experiencing cramps, and having doubts about becoming a mother: “I’m so tired of this silly empty life and realize the baby is going to tie me down tighter than ever” (188). On the next page we read a news account of an explosion on a yacht, in which Dixie was seriously injured. When she learns she has lost the fetus, she declares herself through with it all. Her decent father-in-law arranges a quickie Mexican divorce (and a generous stipend for life), and Dixie agrees to star in Jimmy’s movie Society Girl, “A Sensational Expose of the Haut Monde At Play” as a full-page ad on the penultimate page describes it. The movie is a “smashing hit” (with more fake quotes from real reviewers of the time), and Dixie and Jimmy decide to rest by sailing together for France. Meanwhile, Teddy is already on to his next showgirl, who Walter Winchell informs us (in a tidbit from his column) is “the third gel from the left in Earl Carroll’s Fannyties” (205).[31]

Though Society lacks the hellzapoppin’ energy and jazzy lingo of its predecessors—which in fact would be inappropriate for the leisurely pursuits of the rich and fatuous—the novel is more ingenious than the average satire of high society due, once again, to the novelty of its materials. The title page resembles a formal invitation, set in a copperplate font and even blind-stamped.

Title page from Society

Title page from Society

In addition to the usual letters, telegrams, playlets, and news clippings, we’re treated to Dixie’s ocean crossing diary, shipboard schedules and announcements, formal invitations and cards of introduction, menus, invoices, legal documents, a Junior League report by Serena on “A Trip through a Biscuit Factory,” and best of all, several chapters from The Memoirs of Patricia Page (To Be Opened Fifty Years After Her Decease),” an amusingly self-dramatizing, misspelt account of the 16-year-old’s runaway adventure. There are self-conscious narrative winks from McEvoy, as when the stage direction in one playlet describes the head of the Open Eye Detective Agency as “one of those fiction detectives who can only be found in real life” (33), and when Jimmy remarks on the coincidence of booking a hotel room next to Dixie’s: “If a fellow wrote that in a book they’d say he certainly had to reach for that one” (118). As Jimmy adapts his film plans to fit Dixie’s life, and even asks her to supply background material on debutantes (which she does in snarky fashion), it becomes obvious that his Society Girl is a metafictional mirror image of McEvoy’s Society, a film of the novel/novel of the film.

Pages from Society

Pages from Society

The darker themes in the first two novels are lighter here: sexual predation takes the forms of handsy gigolos and rampant adultery. As early as page 3 Dixie reports that one of Teddy’s rich friends “went right on the make for me—didn’t seem to mind I was on my honeymoon. Teddy didn’t either. Seemed flattered if anything.” A dozen pages later he shacks up with his ex-fiancée, and his tomcatting ways result in the suicide of one betrayed husband. Prostitution imagery is used for both debutantes—their coming out balls are sales displays for the marriage market—and for “society girls who are poor as church mice and yet have to keep up a swank front and be seen everywhere in the swellest clothes and what they won’t do to get by would put a Follies girl’s gold digging into the ‘come into the drug store with me while I get some powder’ class” (18). Patricia’s communist friend reprises Alvarez Romano’s role in Show Girl to introduce political elements in the novel, railing against the decadence of capitalist society in America and aristocratic privilege abroad, which McEvoy records in garish detail.

He also slips homosexuality into the novel. In a brilliantly rendered playlet set in a Paris nightclub called Le Fétiche, two Harvard boys “doing post-graduate field work in abnormal psychology” marvel at the lesbians. “A rosy-cheeked, bright-eyed contralto in tweeds” sings three new stanzas of Cole Porter’s “Let’s Do It, Let’s Fall in Love” (1928), another opportunity for McEvoy to show off his gift for parody:

Bugs do it—

Slugs do it—

Evil-looking thugs in jugs do it—

Let’s do it—

Let’s fall in love.

In holes the nice little mice do it—

Tho they are pariahs—lice do it—

Let’s do it—

Let’s fall in love.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

The Infusoria in Peoria do it—

And the better classes in Emporia do it—

Let’s do it—

Let’s fall in love. (93, 98)

This scene is followed by a letter from a Variety reporter describing the sights to be seen on the way south to the Riviera, including “a little hideaway tucked between [San Rafael and Toulon], entirely populated by the most delightful pixies, male and female, but you’ll never find it unless you meet one of three people, names enclosed here in sealed envelope. They’ll take you there if they like you” (103). In a trilogy about show business, it’s about time McEvoy mentioned the gay element, though it was a daring move for a commercial novelist in 1931.

Though Dixie takes up with high society, she’s never taken in by it. She mocks as she learns “society patter” and affected enunciation, yet can still deliver snappy similes such as “he closed up like Trenton on a Sunday night” (89; i.e., stopped talking). As she occasionally reminds people, she’s still just an Irish “punk” from Brooklyn, and despite a number of poor choices throughout the novel, she retains her best qualities. Teddy’s father praises her “spirit and independence in refusing alimony or settlement” (202), and the news item that concludes the novel indicates she’s single: she has reunited with the love of her life from Show Girl, but she hasn’t married him. Perhaps McEvoy merely wanted to leave the door open for another sequel, but it’s more likely that he intended Dixie to follow in the dance steps of his original model, Louise Brooks, who except for two very brief marriages spent most of her life single. (We can only hope that Dixie doesn’t wind up like our Miss Brooks did.)

Society is blander than its predecessors, but together the Dixie Dugan trilogy is an endlessly inventive portrayal of female independence as well as a damning indictment of show business, politics, sexual attitudes, and society at large. “To those who have followed him since ‘Show Girl,’ Mr. McEvoy has always meant humor and bite,” wrote the Saturday Review of Literature of Society. “The ridiculous and the sharply ironical were always blended,” and though the reviewer felt “the irony has wilted and the humor become worn” in the third novel, it’s that blend of humor and bite, of ridicule and irony—shaken and stirred with linguistic and formal ingenuity—that makes the trilogy as a whole a mordant, madcap masterpiece.

x

Fade to Black: The Final Novels

McEvoy’s 1930 novel Denny and the Dumb Cluck is a spin-off from Show Girl, which documented the failure of greeting-card salesman Denny Kerrigan to convince Dixie to abandon show biz and move to Chicago to marry him. Denny gets top billing in this novel, which begins two years later with a letter dated 11 May 1929 and ends about a year later, and which marks McEvoy’s turn toward darker, more bitter satires of American culture.[32] The novel is festooned with greeting-card verse, whose saccharine sentiments are undercut throughout by the vulgar businessmen who peddle the stuff and the “dumb clucks” who fall for it. Although marketed as a humorous novel,[33] the novel contains attempted suicides, mental breakdowns, divorce proceedings, Chicago mob slayings, and concludes with the murder of the president of Denny’s card company. Even the Hollywood happy ending, in which Denny regales his bride (the “dumb cluck” of the title) with the story of that murder during their honeymoon near Niagara Falls, is undercut by signs of what a terrible husband he will be. The novel is dedicated to Santa Claus.

Like McEvoy’s earlier novels, Denny is an assemblage: letters, press bulletins and newspaper clippings, company memos (some shouting in ALL CAPS), telegrams, divorce papers and trial transcriptions, a hotel bill, two lengthy monologues, and selections from a lonely hearts newspaper column penned by “Carolyn Comfort”—actually a “white-haired [male] tobacco-chewing reprobate” (148).[34] It differs from his earlier novels in its structure: they proceeded chronologically, with their multiple story-lines interlaced, but Denny is divided into eight semi-independent sections that focus on specific story arcs. Part 1, dated from 11 May to 12 June 1929 concerns Denny’s modus operandi to selling the Gleason Greeting Card Company’s wares to the female owners of card shops (all with twee names like “Ye Arte Moderne Snuggery”); as he writes to his supervisor Al Evans, this entails “taking out the lady buyers and getting them all warm and confused so they’ll overstock themselves and have to work like hell making profits for you and me eh Al?” (22).[35]

Pages from Denny and the Dumb Cluck

Pages from Denny and the Dumb Cluck

At loose ends one Sunday in Chicago, he meets “the dumb cluck”: a young woman named Doris Miller, estranged from her rich family in Indiana because she moved to Chicago “to make her own way” as a singer—another of McEvoy’s admirably independent young women. But when Denny recites one of his company’s lovey-dovey greeting cards and passes it off as his own spontaneous creation, Doris falls for him. “Poetry always gets dames,” he smirks to Al (15). But after she spots the poem in a greeting-card shop window, she attempts to drown herself. She is rescued, then explains her reason for the attempted suicide to a reporter who gussies it up for a human interest story for the Chicago Herald Examiner (reproduced on pp. 23–25), which leads to a spike in sales for the “Heart Throb” card Denny quoted. Denny hears about the sales but is unaware of his role in the spike.

The next section, however, begins with a letter by Al dated more than two months earlier (3 March) instructing his salesmen to make a big push for the new idea of a Father’s Day card, and concludes with a newspaper report dated 17 June 1929 noting Al’s admittance to a sanatorium for a nervous breakdown, the result of his stress-inducing sales efforts. This section features heart-rending letters from his wife to her mother on the disastrous effects of his work on their marriage, and also introduces the Gleason Company’s “staff Poet Laureate” (3), Terence McNamara, a hard-drinking party animal (obviously a stand-in for McEvoy himself) whose marriage is likewise troubled. Section three is undated but apparently takes place in April, for it deals with sales plans for Mother’s Day cards. Denny gets nowhere with the proprietor of Ye What Ho Gifte Shoppe, “One of those long legged short-haired Greenwich village gals that wear batik bloomers and talk about their complexes” (60). She has eyes only for a milquetoast customer who shops frequently for cards to send home to mother. (In an ironic twist typical of McEvoy’s novels, he turns out to be a hired assassin.) Denny reports to Al about a crime wave in Chicago, and passes along his (and apparently his creator’s) doubts about his profession and his country: “Boy, you and I picked a piker’s game when we decided to spread cheer throughout the land. It’s nothing to cheer about if you ask me” (69).

Section four documents McNamara’s divorce proceedings, dated between 14 September and 5 October 1929.[36] His wife testifies to his numerous drinking binges on greeting-card related holidays and irresponsible behavior, including the time when McNamara flipped out when his kids recited a Valentine’s Day greeting-card poem to him. But when the poet takes the stand, he wins over judge and jury by answering entirely in greeting-card “sediments” (as it is often spelled in this and other McEvoy novels).

Pages from Denny and the Dumb Cluck

Pages from Denny and the Dumb Cluck

The final four sections are undated. Section five apparently takes place later in October 1929, for greeting-card president George Gleason is in New York City looking for a replacement poet after firing McNamara for bad publicity. This startling section is a 23-page monologue delivered by Gleason to a Ziegfeld showgirl in his hotel room—she is currently dancing in Whoopee!, which closed 23 November 1929—whom he plies with liquor and tries to seduce until she panics and attempts to jump out the window. In section six, which seems to take place in late October or early November (though there’s no mention of the Wall Street crash during the last week of October), Denny searches for Doris, while the dumb cluck pours her heart out to Carolyn Comfort’s lonely heart column. Section seven must be set in late January of 1930, for football season has just ended and Denny is peddling Valentine Day cards. He’s having a difficult time making a sale to the owner of Ye Merrie Lyttle Nooke in South Bend, Indiana, “a little pug-nosed Mick” who is distracted by unrequited love for a theology student at Notre Dame, and is secretly contemptuous of her wares: “There is a card lying here on the table before me as I write, a sample Valentine given me by that fool salesman, Denny Kerrigan, who sells the Gleason line. It says ‘Love is bright as sunshine, love is sweet as dew’ and a lot more. But it isn’t anything like that at all, darling. Love is bitter and dark and cruel beyond all the cruel dark and bitter things of this world” (177). Her heartbroken letters to the student express true emotions in stark contrast to the false ones offered on greeting cards. After reading a newspaper announcement of her beloved’s ordination into the priesthood, clueless Denny writes to the woman about his new idea for a line of cards: “CONGRATULATIONS ON YOUR ORDINATION.”

The final section jumps ahead a few months to Denny and Doris’s honeymoon, and is mostly taken up by Denny’s account of George Gleason’s murder the previous February by a disgruntled customer. There’s no explanation for how Denny found and made up with Doris, for since Denny is talking to her (another one-sided monologue to a silent woman), there wouldn’t need to be. Doris obviously knows how it happened, but the reader doesn’t, who might be excused for thinking McEvoy grew impatient and didn’t want to write a penultimate section on their reunion and courtship. Denny had suffered some sort of accident in section six that entailed a hospital stay with his face in bandages, and unbeknownst to him Doris nursed him and took dictation for his letters to Al about his search for “that dumb cluck” (156). They obviously reconnected, so McEvoy apparently felt he could cut to the honeymoon and wrap it up.

Despite the ostensibly happy ending, this is a harsh novel, which is to be expected from an author who set out to write a “grudge book” to “get even” with the greeting-card industry, as he admits in the author’s note at the end. It was too harsh for some reviewers: “The book is American in the same way that chewing gun, comic supplements and loud speakers are American,” complained Edwin Seaver in the New York Evening Post. “It is a violent, noisy book.” Contemptuous of the publisher’s attempt to market the novel as light humor, V. P. Ross wrote, “It is too ugly to be delectable, too grotesque to be tragic, and too longwinded to deserve the laurels of humor.”[37] But it is precisely those qualities that give Denny and the Dumb Cluck its edge, its Voltairic clash between ideals and reality, its anticipation of the irony-clad black humor of 1960s novels. A standard boy meets-loses-marries girl novel taking jabs at greeting cards would be too simple. McElroy used that sideline to stand for American business practices in general, many aimed at persuading “dumb clucks” to purchase their goods and services. He even hints that the New Testament’s promises of immortality are as false and hollow as greeting cards when Denny flips through a Gideon’s Bible in a hotel room.

The language isn’t as slangy as that in the Dixie Dugan novels, though there are some amusing euphemisms (“you illegitimate sons of Rin-tin-tin’s mother”) and synonyms for drinking binges (“out on a bat”). There is also what appears to be McEvoy’s self-conscious defense of his “humorous” approach to writing versus that of “serious” writers, many of whom flocked to Paris in the 1920s. Denny writes to Al about the old drunk who writes the lonely hearts column:

For years he has done everything in the newspaper racket and found that nobody cared, so now he runs the Lonely Hearts Corner and hopes to save enough money to retire and go to Paris to write a novel. He says he needs a couple of years off from the job so he can gather material. I says, what about all these letters you get from the Lonely Hearts? I should think that would be swell stuff for a writer. A lot of hooey! says he. Now, take that story you were telling me about that girl you tried to find—you know, the one you picked up in a restaurant and took for a lake ride. She jumps off a boat because she thinks you wrote those bum sediments you’re always quoting! Well, I don’t blame her. I’d jump off myself to escape you. Now, I suppose you think there’s a story in that? Sure, says I. Crazy, says he. That just proves you’d better stick to peddling cheer. You’d starve to death if you tried to write. Now me, for instance, I know how, but I’ve nothing to write about and I can never save up enough to get ahead and settle down for a couple of years to do serious work. You know my dream, says he. I want to get a little studio in Paris near Montparnasse, and just sip wine, nibble cheese, and observe life and write about it. (150–51)

You can imagine what that novel would be like, if the old sot ever got around to writing it. But McEvoy did find “a story in that” attempted suicide, a polyvalent one that expands to indict all of American society at the bitter end of the Roaring Twenties when it all came crashing down, and didn’t need to take a few years off in Paris to write it.

***

Having settled his score with the greeting-card business, McElroy turned next to the comic-strip industry. The first half of Mister Noodle takes place in Chicago, where McEvoy got his start in strips, and I can’t improve on the plot summary provided by James A. Kazer in The Chicago of Fiction:

The story of Charlie “Chic” Kiley from Gum Springs, Illinois, is told through letters to his mother, news clippings, telegrams, and transcripts of conversations. Kiley takes drawing classes at the Art Institute and works in the art department of the Chicago Star. Overnight he becomes a nationally known comic strip artist when he introduces Mister Noodle, a strip composed only of profiles (since that is all Kiley can draw). He also effortlessly achieves social status, receiving memberships in the Chicago Athletic, Forty, and Midday Lunch clubs. With his newfound security he is able to marry his girlfriend and he soon has a one hundred thousand dollar per year contract for his syndicated strip. However, when he relocates to the syndicate’s offices in New York City he succumbs to the temptations of beautiful women, nightclub entertainments, and drink. When an actress falls from the balcony of his penthouse the scandal fills the Midwest with moral indignation and his comic book gets cancelled. Only when he returns to Chicago and reconnects with his small town does he get the inspiration for a new comic strip and rediscover success. This satire of the syndicated comic book industry makes pointed comparisons between Chicago and New York to the detriment of the latter.[38]

Arthur William Brown illustration, Saturday Evening Post serialization of Mr. Noodle

Arthur William Brown illustration, Saturday Evening Post serialization of Mr. Noodle

It’s important to note that the novel satirizes only certain aspects of the comic industry, specifically the undeserved success of certain hacks and low-brow taste of many readers. The first time Kiley submits his poorly drawn strips to the editor of the Chicago Star, his boss tells him, “This paper has printed hundreds of questionnaires and prize contests for the correct answers on the simplest subjects, and we have found by experience that the average person knows only three things. . . . He knows his name; he knows his parents; and he knows where he lives. And that’s all he does know. Remember that if you’re going to be a comic-strip artist. . . . Always tell ’em something they already know. The better they know it the better they like it” (41). Talentless hacks pandering to the lowest common denominator is what irked McEvoy, not the genre itself; later in the novel, when a Russian director named Ivan Stalinsky sails to America to make a movie of Kiley’s strip,[39] the director expresses what might be McEvoy’s own views during a gangplank interview with the New York Evening Tab (the same rag that figures so prominently in Show Girl):

“The comic artist is the real modern artist. Comic artists were the first expressionists, and the colored supplements in your Sunday papers, with their vivid reds and greens and blues, are brutal and frank as the life they underscore, and it is only because I have always made pictures with real people rather than actors that I welcome this opportunity to come to your America and make a new comédie humaine, using the real Noodles of American life to reënact and interpret the salty humors of everyday existence. . . . You can say for me,” he added, “that the Supreme Author is a Humorist, and Life is a mad comic supplement He created to amuse the angels.” (125)

McEvoy placed the final sentence upfront as the epigraph to the novel, but then again, the entire statement may only be a swipe at the lofty claims sometimes made for the genre. The author definitely has his tongue in cheek when Kiley’s editor tells him, “Don’t forget the last frontier of old-fashioned virtue is the comic strip” (47).

Unlike the previous novels, the documents that make up Mister Noodle are not dated, except for a clip from Vanity Fair on the last page dated 1932, a year after the novel was published. Apparently the events occur between 1929 and 1930—a character on page 71 recites lyrics from “Just You, Just me,” a hit song introduced in the 1929 musical Marianne, though again there’s no mention of the Crash of ’29—and everything happens at a more rapid pace than in the previous novels, effectively conveying the “overnight-success” aspect of Kiley’s career. This is a deliberately unfunny novel about the funny papers, featuring one of McEvoy’s most despicable protagonists. Not only is he talentless, but he owes his success to others: his girlfriend Dorothy—whom he meets at the Art Institute and later elopes with—gave him the idea for the strip in the first place, which Kiley then adjusts to his boss’s low view of comics (which Kiley later parrots as his own). After he becomes successful, he has a team produce the strip for him while he gallivants around New York City, and even when he returns to Illinois in disgrace at the end, he has learned nothing. Kazer’s description of the conclusion is misleading: Kiley returns to Gum Springs to recuperate, but is subjected to a brilliantly rendered monologue by his ignorant Irish Catholic mother about murders, mayhem, and madness out in the sticks: hardly the stuff of inspiration. When Kiley then meets with his former Chicago Star editor and claims he has ideas for a new strip, he junks them as soon as his boss feeds him an idea for a new strip called Mister Whoosis, which Kiley claims for his own creation when he boasts to his New York syndicate boss of his imminent return to the big leagues. The novel ends with another hick comic artist arriving in the New York and getting carried away at the idea of living the high life, obviously on course to repeat Kiley’s fall. Or not: the last page of the novel reproduces a clip from a future issue of Vanity Fair stating, “We nominate for the Hall of Fame, Willie Timmerman, because—“ (186).

Arthur William Brown illustration, Saturday Evening Post serialization of Mr. Noodle

Arthur William Brown illustration, Saturday Evening Post serialization of Mr. Noodle

The Chicago Star editor’s final lecture to Kiley is a cynical but informed overview of the comic-strip business, especially its lack of originality, and undoubtedly represents McEvoy’s conclusions after fifteen years in the business. When Kiley tells him that he has an idea for a strip that has never been done before, the editor (named James P. Mason) cuts him off:

Worse. Doomed to failure. The most successful strips running today were always successful, long before they were strips. Mutt and Jeff was a big hit when it was called Weber and Fields, and it’s a bigger hit now when it’s called Amos ’n’ Andy. Same idea. Big dumb guy picking on a little smart guy. German dialect, colored dialect, Brooklyn dialect—same thing. Little Orphan Annie is Cinderella. Bringing Up Father—Abe Kabibble—every burlesque show for the last fifty years has had a Jiggs and an Abe. The Gumps? Mr. and Mrs.? Any family comic? Has anything ever happened in any of ’em that hasn’t happened a million times in a million homes?

CHIC: I know, but they aren’t funny.

MASON: They don’t have to be funny. Did you ever watch anyone read a comic page? Did you ever see him laugh? Was there ever a laugh in Little Orphan Annie? One of the most successful comic strips running. People don’t want to laugh so much as they want to feel superior to somebody else. (179–80)

There are discussions like this throughout, with references to many strips and comic artists, which should make Mister Noodle valuable for comic historians, written by someone who was there at the beginning. For literary historians, Mister Noodle is valuable as a demonstration of how to take an unoriginal story-line (rube seduced by the big city) and make it new by way of formal and linguistic innovations. In addition to McEvoy’s usual documents, which as always provide a you-are-there immediacy to the proceedings, there are some amusing parodies of the gossip columnists of the time. Kiley’s arrival in New York is announced by a word-drunk columnist reaching for the literary stars:

AVE! MISTER NOODLE!

An Inquiry into the Irrefragable Tenuities

(From the Editorial Page of the New York World)

Swims into our ken a new planet—the algebraic mystification of orbital aberrations, the torturing ellipse of tortured ellipses, the Theseus before the throne of the Minotaur, half bull, half man, quaint Cretan symbol of American ideology—Mister Noodle—planet X—crying in the wilderness, eating the wild locusts of ephemeral fame, preparing the way for a greater-than-he, forsooth, or peradventure, if you will quibble—but I shout “Gold! Gold!” as did wild-eyed Sutter long ago—and mayhap I will grant you, a Fool’s Gold, but your Au may be my FeS₂, and who will bid me nay, for fool’s gold is the guerdon of fools—always the king on the throne has paid the fool on the stool stones for bread, darkness for light, the louring brow for the laughing lip—and so, in like manner—Measure for Measure, said the Mortal Poacher with immortal finality, or vice versa—we too long and too smugly, I fear, have been paying Mister Noodle of the earth earthy—Punchinello Redivivus!—with Jovian frowns from our high, crystal parapets, remembering not that Jove walked with the sons of men by day and talked with the daughters of men by night—Danaë? Shower of gold? FeS₂? Why not?—and from the little despairs of men, brewed by an alchemy lost to us the great courage of the gods against the cosmic crepuscle of the Götterdämmerung. (Ya sagers, all, shouting in the terrible twilight that finally swallowed warm, shining Olympus and cold, dread Erebus alike.) Vale, Great God Pan! Ave, Mister Noodle! (97–98)[40]

Columnist Walter Winchell is parodied twice, once upon Kiley’s arrival and once after his disgrace: “A certain cocky alien from Chicago, who was King Fish in the ookie-ookie racket a few months ago, and then faw down on his you-know-what with a big phfft is out of the camphor again and trying to merge a meal ticket on a local rag . . . no soap” (163). On the train from Illinois to New York, Kiley makes the acquaintance of “The Boop-a-Doop Sisters,” two nightclub chippies who provide an sassy stream of slang throughout the rest of the novel, even some pig Latin.

As in his previous novels, McEvoy takes the faults of a minor—some in the 1920s would have said trivial, even disreputable—medium of pop culture as a metonym for the faults of America at large. He presumably wrote Mister Noodle in the gloomy months following the Wall Street crash, which perhaps justifies the New York World columnist’s despairing evocation of Wagner’s Twilight of the Gods. Reviewers used to the fizzy fun of the Dixie Dugan novels were shocked at the novel: one complained “Its humor is cruel,” another that “There is a great deal that is coarse and unnecessarily realistic,” and a third that it “is hard, brittle, cruel almost to literary sadism”[41]—which sound like the reviews Faulkner’s Sanctuary received the same year. Neither Mister Noodle nor Society (also published in 1931) sold well, and perhaps for that reason McEvoy changed publishers for his final novel.

***