In this age of addiction and excessive consumption where massive modes of pleasure are readily available, have we completely fucked ourselves into oblivion? Do we give a fuck about fucking anymore? And now that we have come to the point of post-structuralism, post-modernism, post-privacy and post-truth, have we also arrived at the era of post-pleasure? —Melissa Considine Beck

Coming

Jean-Luc Nancy with Adele Van Reeth

Translated by Charlotte Mandell

Fordham University Press, 2016

168 pages, $22.00

.

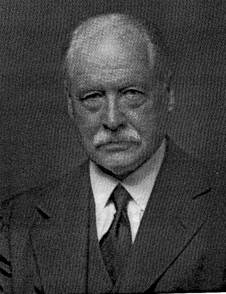

In this age of addiction and excessive consumption where massive modes of pleasure are readily available, have we completely fucked ourselves into oblivion? Do we give a fuck about fucking anymore? And now that we have come to the point of post-structuralism, post-modernism, post-privacy and post-truth, have we also arrived at the era of post-pleasure? There are just a few of the provocative questions that French philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy raises in his book Coming as he explores the tricky, elusive and titillating French word jouissance and its various associations with orgasm, sex, coming, pleasure, joy, property and consumption.

Coming, which is the English translation of the French title la jouissance, takes the form of an interview, divided into five part as Adèle Van Reeth, the producer and host of France Cultural Radio’s daily program on philosophy, asks Nancy a series of questions about the idea of jouissance. Through the course of this dialogue, Nancy lays out the original meaning of jouissance, which was used solely as a legal term, and he takes us on a fascinating linguistic journey to discover how this word evolved to become associated with sexual pleasure and orgasm and from consummation is now associated with the modern idea of consumption. This book is an excellent introduction for those who are new to Nancy or for those who are familiar with his prolific writings as it contains some of his most favored topics: community, modern psychology, linguistics, Christianity, the body, sex and Platonism, just to name a few.

Nancy made the suggestion of using the infinitive, “To Come” for the English title of this book but Charlotte Mandell thought that the gerund “Coming” would be a better choice to capture the continual nature of movement associated with jouissance. Included in the edition published by Fordham University Press is a beginning note that Nancy writes himself in which he explains the problem with rendering jouissance into an appropriate English title:

In English, sexual orgasm is expressed by the verb “to come.” This has no corresponding noun. What is shared by both lexical registers is an idea of accomplishment. In French, we say venir (to come) for “reaching jouissance,” but the word is mostly used between sexual partners (“viens!” for example.) In choosing the gerund “coming,” Charlotte Mandell aptly brings out action or movement, something that is in the process of occurring, which, in fact, is attached to jouissance and to jouir; that is, precisely, what remains irreducible either to a state or to an acquisition, to an accomplishment or to an appropriation.

It is interesting to note that throughout the text of Coming, jouissance is simply translated in brackets as “pleasure” or is not translated at all, a constant reminder of the elusive nature of this word that has no equivalent translation in English.

.

Defining Jouissance: What the fuck does this French word mean?

Nancy is a master at speaking about the nuances of language and uncovers, unpacks and explains specific French words, with their etymological roots in Latin, that are closely related to jouissance. He begins the discussion with an examination of the French verb Jouir, which means “to enjoy” and “to have an orgasm,” and is derived from the Latin verb gaudere, “to rejoice,” and therefore has no etymological relationship to sex or sexuality. At some point there is a shift in meaning of jouissance from property to sexual pleasure and orgasm. Nancy speculates that this shift begins with the middle French use of joie (joy) which denotes the sensual or sexual feelings of the troubadour poets; these poets have a joy of love that is sensual but jouissance, in the sense of reaching orgasm, is avoided. Nancy exclaims, “One of the ordeals of courtly love even consisted of the knight sleeping with his lady without making love!”

He further explores this shift in meaning by comparing the French words jouissance [pleasure] and joy [joie] and how they are different. Nancy argues that jouisssance corresponds to what Kant called pleasant—when something is pleasant it is something that is felt inside of me because something suits me. Joy, however, is outside of me and carries me towards something else. Nancy goes one step further in the etymological connections of various words to jouissance and explains réjouissance (rejoicing), whose root and meaning are very close to jouissance. Nancy points out that réjouissance is not used very often today and when it is used it describes something that is public such as popular festivities. Nancy concludes about the etymological connection between réjouissance and jouissance:

The idea of festivities, réjouissances, refers to festive excess, to a certain suspension of everyday activities, but also to obligation and finality. That is where we find jouissance, in the sense of joyful acclamations greeting the arrival of an important person, like the jouissance of the people at the arrival of the king.

We can say, then, that joy and réjouissance are like jouissance in that they all denote an excess. The idea of excess and its association with jouissance will be a topic brought repeated throughout Coming. Jouissance is an experience of excessive sexual pleasure in the form of orgasm which experience we seek over and over again.

.

Jouissance as a shared experience: Is it possible to fuck alone?

The style of interview works exceptionally well for Coming because not only does Van Reeth adeptly sum up Nancy’s complicated thoughts, but she also asks him precise questions which elicit more of his ideas; Van Reeth is able to challenge Nancy to expound on his positions and she keeps the dialogue moving forward rather fluidly. In this part of the interview that deals with the subject and the object in the context of jouissance, Van Reeth begins:

Jouissance as experience implies a dissolution of the subject as well as the impossibility of appropriating its object. How then can we define what makes us enjoy [jouir]? And above all, since the question of object goes back to that of the subject: Who is it that enjoys [jouit]?

Nancy insists that jouissance has no specific subject because I am not the owner of my jouissance. How can it be possible for a person to own an orgasm if his or her sexual climax involves another person, another body. What I take pleasure from is just as much my pleasure as it is the pleasure of the other with whom I am engaging in a sexual relationship. Nancy brilliantly anticipates his critics who would argue that masturbation disproves the nonexistence of subject and takes his argument a step further by stating that when pleasuring oneself the other is still present in the form of a fantasy. So when we fuck, we are never fucking alone even if there isn’t another physical body in the room.

It during this part of the discussion that Nancy brings up Lacan and his exploration of jouissance in relation to the pleasure principal. Lacan believes that a subject attempts to go beyond, to transgress the pleasure principal and this brings about pain. It is with this excess, with this reaching of pleasure beyond a limit that Lacan defines jouissance. Although Nancy has been critical of modern psychology throughout his career, he credits Lacan with his effort “to try to find the meaning of jouissance, beyond the fulfillment of satisfaction, into a sortie, outside oneself, into exuberance, ecstasy….”

Van Reeth’s importance in this philosophical exchange is underscored in this section as she further presses Nancy on Lacan’s examination of jouissance:

How do you understand Lacan’s phrase asserting there is no sexual relationship? If there is no sexual relationship, there is no sexual jouissance. But wouldn’t it be truer to understand not that jouissance is impossible, but that it is inconceivable? Just as the fact that there is no sexual relationship would signify that there is no thinkable relationship. It would be a way to preserve the space unique to jouissance as experience.

Nancy’s insight into Lacan is a starting point for his thoughts on jouissance as a shared experience and it will also serve as a prompt from which to discuss the links between aesthetic and sexual jouissance in the next section of the interview:

That is probably what Lacan means. ‘There is no sexual relationship’ can be understood in several ways: There is no proportion, no commensurability, no conclusion either. The sexual relationship cannot be written down. The implication is: there is no account of it, no ‘report’ [rapport, which also means ‘relationship]’ But it is precisely to that extent that there is a real rapport, which demands incommensurability and a form of non-conclusion. A relationship is maintained [s’entretient]. It is not completed. A completed, accomplishment is either a breakup, or a fusion. And in fusion there is no longer any relationship. It would be truer to say, then, that jouissance is inconceivable, not impossible.

In sum, pleasure comes down to a matter of shared meaning whether there is a sexual partner or not. At the end of this section dealing with subject and shared pleasure, Nancy makes one of the simplest, yet thought-provoking statements in this entire volume: Where does sexuality begin and where does it stop? He concludes, “Perhaps it begins very, very far from the sexual act itself.”

.

Aesthetic and Sexual Jouissance: Fucking in motion

Even though Nancy argues that jouissance is never a solitary experience, he also explains that pleasure is unshareable, much in the same way that aesthetic pleasure is a singular experience, unique to each individual. As he opens thoughts on the link between sexual jouissance and aesthetic jouissance, Nancy points out that it is Freud who first establishes the transfer of aesthetic jouissance to sexual jouissance. Nancy’s criticism of psychology becomes apparent as he disagrees with Freud on his speculation that there is a specific order in which seduction happens—gazing, hearing, touching, must happen first, Freud argues, and only at the end of this progression does Freud finally come to the genitalia through which the tension in the form of orgasm is released.

This part of the discussion in which Nancy brings his reader to understand the connection between sexual and aesthetic jouissance is typical of his very dense, erudite, and multifaceted writing. He references various texts of Freud, he dissects more Latin words via Spinoza, he mentions the young Chilean philosopher Juan Manuel Garrido, he quotes David Hume, and he reaches all the way back to the ancient texts of Plato to make a point about pleasure. As I carefully read his text which is thick with history, philosophy and literature, I take notes, I read or reread authors whose books are sitting on my shelf to whom Nancy has referenced, I search the Internet for authors unknown to me, which laborious activities sometimes feel like a feeble attempt to absorb the full scope of his genius. But all of a sudden, at the end of a complicated series of thoughts, Nancy composes a short, simple, beautiful, concise paragraph that grabs me so forcefully that I pause my frenzy of research:

What we enjoy in an aesthetic form is the movement of this form, even though it ends up being completed. What’s more, an aesthetic form is probably never exhausted and, on the contrary, does not stop enjoying itself (jouir d’elle-meme).

And a bit further on in the same discussion:

In jouissance, they [bodies] become almost formless. Which is radically opposed to that call to eroticism, in advertising or movies, always summoning beautiful, perfected forms. Whereas in eroticism, in eros, these forms become undone.

Nancy reveals in these two simple yet erudite statements that in art there is no formula for what is considered beautiful. Furthermore, we can carry this over to jouissance in which there is no formula to be followed; each person experiences beauty, art and sexual jouissance in his or her own unique way this experience is impossible to share. In a relationship there are no accepted forms or defined forms of beauty, these forms are uniquely decided by the persons within a relationship.

.

The Creative Power of Jouissance: Is There an Art to Fucking?

Nancy’s discussion of the link between sexual and aesthetic jouissance, with a particular emphasis on the art of writing, is the most accessible and interesting piece of this interview. Nancy argues that even when an artist produces a jouissance in his or her viewers, there is always a constantly renewed dissatisfaction that keeps the artist working again and again. “The artist,” he argues, “is in action in his work, and he also takes pleasure [jouit] from being in the process of working. He suffers too, it’s always laborious.”

Nancy is a prominent and well-known contributor to the studies of art and his cultural writings have covered the topics of literature, poetry, theater, music and film. Nancy has written books on the subject of art and has also written pieces for international art journals and art catalogs. He has a text from a lecture given 1992 at the Louvre displayed with the painting ‘The death of the virgin’ by the Italian painter Caravaggio. It is fitting that Fordham University Press has used a Caravaggio painting for this edition of Coming thereby reminding us of Nancy’s interest in the Italian painter.

In order to lead Nancy into elaborating on the similarities between the pleasure of art, specifically the art of writing, and sex, Van Reeth reads a passage from Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet in which the author asserts that writing and sexuality bring about the same pleasure. In a letter dated April 13, 1903 from Viarregio, near Pisa, Rilke writes:

And in fact artistic experiences lies so incredibly close to that of sex, to its pain and its ecstasy, that the two manifestations are indeed but different forms of one and the same yearning and delight.

Nancy picks up on the idea that Rilke is speaking of writing as working toward the unknown, without a goal, which is also true for artists who work with music or paint. The art passes through the artist to the spectator who experiences the work of art through a plethora of senses. In the end the artist has no real understanding of how his or her work is received, of the various ways in which someone experiences pleasure through his or her art. The pleasure that is experienced by the spectator as a result of interacting with his work is unshareable just as the experience of sexual jouissance. When we speak about sexual pleasure and orgasm, is there really a word or phrase that captures a good fuck? How can we truly and accurately describe the best fuck we’ve ever had? The experience is unshareable when we make any attempt to put it in words.

The true brilliance of Nancy’s dissection of language comes with his elaboration on the verbal similarities of art and sex. Artistic media such as color and rhythm are used to describe both art and sex. Rhythm, for instance, is present in an art’s use of color and can also be applied to the lover’s caress of the body. The best sex is enjoyed when lovers find a rhythm and Rhythm is a coming-and-going, a constant movement a repetition. Nancy concludes about rhythm:

Rhythm in general is born from what is never definitively there, from what does not stay in place and causes us to return, what leads to jouissance. Rhythm is fundamental for humans, bur for nature as well; think of the rhythm of the stars.

Art and sex cannot exist without movement. It is the seduction, the process, the rhythm that leads to artistic and sexual jouissance

.

Suffering and Fucking—Christianity’s Influence on jouissance

The fourth part of the book, dealing with Christianity and its influence on jouissance is the shortest and the least stimulating part of the dialogue. Nancy has been interested in and critical of Christianity throughout his career and we get a cursory survey of his thoughts in this section. Throughout their dialogue on pleasure, Nancy and Van Reeth both tangentially bring up the close relationship between pleasure and suffering. Nancy sites the works of de Sade as an example of jouisssance being the result of pain inflicted on another or on oneself. Pain and pleasure have an intensity in common and in the moments before orgasm the tension that one experiences can be painful. Van Reeth uses the example of Proust’s narrator who, in the beginning of Sodome et Gomorrhe, describes the very noisy sexual encounter between Baron de Charlus and Julien as akin to the sound of a man having his throat split. The narrator concludes, “if there is one thing as loud as suffering, it’s pleasure.”

Nancy begins the section by arguing that Christianity was the calming solution to the disintegration of the theocratic regimes, the loss of which political system caused great anxiety and unrest. Christianity brings to mankind the idea that life is simply a passage to another spiritual side, a passage that is marked by suffering. It is the Passion of Christ that provides us with a redemptive kind of suffering and suffering is specifically attached to life on earth. One must pass through suffering in this life in order to attain salvation. As a result there is a definitive break and distinction between heavenly joy and human joy. Because of Christianity’s condemnation of the flesh, earthly pleasures such as human joy and jouissance become evil and separate from heavenly joy and jubilation. It is fitting that their discussion on Christianity and suffering, even in relation to jouissance, is the most somber part of Van Reeth and Nancy’s dialogue.

.

From Consummation to Consumption: Do we give a fuck about anything anymore?

Nancy explains that Christianity was an attempt to organize people into one community, but the appearance of a modern state served to divide individuals until the invention of capitalism. “which would insert the individual subject into the circuit of a new jouissance: no longer the jouissance of excess, but that of accumulation and investment. It’s a jouissance that can no longer bear that name.” Van Reeth asks Nancy what, exactly, has changed to cause the meaning of jouissance to shift once again.

It was Communism, Nancy argues, that provided the connection between jouissance and profit, which political theory believed that everyone’s hard work will produce profits that can be equally shared by all –this sharing of profits would be a source of jouissance. But nowadays, people are working harder than ever and the profits are accumulated by a very small percentage of the upper classes. Nancy argues that jouissance has now come full circle to be associated with its legal meaning which is that of possession and acquisition.

Today, jouissance has become confused with and associated with profit as well as property. Excess has now taken on a quantitative definition in that we must possess the greatest possible number of things that we can. Nancy concludes: “It has left heaven, joy, to land again on earth.” With the ubiquity of things that we consume that push us to the brink of addition—little blue pills, a plethora of opiates, internet pornography—jouissance today has evolved into a kind of greedy consumption in which excess has become the norm. With the disappearance of excess what is left that gives us pleasure? Have we landed in an epoch of post-pleasure?

In this final part of the dialogue when Nancy brings up modern ideas of consumption and their relation to jouissance he shows that he has continued to think about philosophical topics and how they can be applied to current social and political situations. Orgasm, masturbation, sexual pleasure, addiction, and jouissance itself are topics that seem more fitting for the field of psychology and have not been explored by philosophers. Despite his years of suffering through grave illnesses and his advanced age, Nancy proves in the publication of Coming that he is as relevant and progressive as ever in his field.

Although Coming is a short book, some might be intimidated by the breadth and depth of Nancy’s thought. It is, however, an excellent and thorough introduction to the wide range of ideas on which Nancy has expertly written and a scintillating discussion of pleasure, sex, orgasm, fucking, desire, pain, and how we experience these things with our bodies. The interview style of the text in which Van Reeth summarizes Nancy’s main points and propels the conversation forward with her questions makes Coming one of his most accessible and fucking enjoyable books.

—Melissa Considine Beck

N5

Melissa Beck has a B.A. and an M.A. in Classics. She also completed most of a Ph.D. in Classics for which her specialty was Seneca, Stoicism and Roman Tragedy. But she stopped writing her dissertation after the first chapter so she could live the life of wealth and prestige by teaching Latin and Ancient Greek to students at Woodstock Academy in Northeastern Connecticut. She now uses the copious amounts of money that she has earned as a teacher over the course of the past eighteen years to buy books for which she writes reviews on her website The Book Binder’s Daughter. Her reviews have also appeared in World Literature Today and The Portland Book Review. She has an essay on the nature of the soul forthcoming in the 2017 Seagull Books catalog and has contributed an essay about Epicureanism to the anthology Rush and Philosophy..