‘Beauty is truth, truth beauty,’ — that is all

Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.

— John Keats

Chlamydomonas is my favorite “model organism.” It is a small green alga that is one of a handful of unlikely organisms that serve science by acting as proxies for the human body. Scientists don’t pick so-called model organisms for exceptional evolutionary achievement and there is no scientific catwalk of gorgeous creatures. Some scientists do exclaim over the beauty of these creatures, but really. Pond scum? Writhing white round worms? Slime mold? The truth is, model organisms are a haphazard lot that scientists select from the teeming crowds because of quirks that make them useful for laboratory research. They are useful and as we work with them we come to know them.

Thank Evolution

Life on Earth emerged relatively soon (0.7 billion years) after our Solar System formed and it has been evolving ever since (i.e. for 3.8 billion years). Because all of life on Earth shares fundamental biochemical pathways, it is likely that we are all descended from a common ancestor – presumably the most robust of the emergent life forms. This commonality means that studies of almost any organism can shed light on the others.

In this Tree of Life diagram the centre represents the last common ancestor of all life on earth. Pink are the eukaryotes (plants, animals and fungi); blue are the bacteria and green are the archea. Humans are second from the rightmost edge of the pink segment. The species included in this illustration are those whose genomes have been sequenced. (Courtesy of FD Ciccarelli).

In this Tree of Life diagram the centre represents the last common ancestor of all life on earth. Pink are the eukaryotes (plants, animals and fungi); blue are the bacteria and green are the archea. Humans are second from the rightmost edge of the pink segment. The species included in this illustration are those whose genomes have been sequenced. (Courtesy of FD Ciccarelli).

When word gets out that an organism is well suited to a particular type of experiment other scientists interested in related problems begin using this species for their work. Over time, we learn a great deal about the organism and along the way we develop an array of experimental tools to study it. With the application of these tools, the organism expands its repertoire of usefulness to science. In other words, a few assets and a great deal of happenstance get the ball rolling. As our knowledge of an organism and our skill in working with it increase, the organism becomes established as a model.

.

Microscopic Models

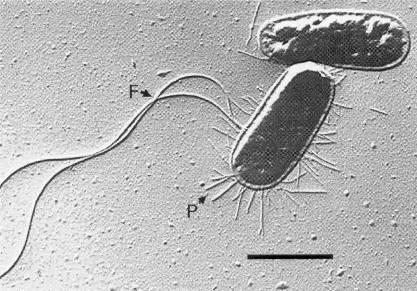

E. coli, the infamous gut microbe variants of which can wreak havoc with human health, grows rapidly and is one of the easiest beasts to study in the lab. It and a few other bacteria serve as models for understanding microbial-based pathogenesis. They also serve as tools for the experimental dissection of fundamental biochemical processes. From these studies we have learned that although bacteria are small, they are surprisingly sophisticated and are by no means simpler versions of us. They branched off early and have taken a different evolutionary path than us. Because of this divergence, E. coli is of limited use as a model organism for understanding how human cells work.

Electron microscopic image of E. coli courtesy of MediaWiki

Electron microscopic image of E. coli courtesy of MediaWiki

We tend to think of ourselves as more highly evolved than, well, everything else. This is a strange idea given that every living thing has an evolutionary history as long as ours. We confuse evolutionary longevity with complexity. While we are no more highly evolved than any other being on Earth, we are arguably the most complex beings in an evolutionary lineage that specializes in complexity, a lineage we call the eukaryotes.

Around two billion years ago, by a process that seems to have involved some early cells engulfing other early cells and them all coming to live in peaceful co-existence, the eukaryotic lineage was born. These larger and considerably more complex cells, containing what have since become nuclei and mitochondria, allowed a blossoming of innovation, including complex multicellularity.

Under conditions of starvation, free living single cells of the slime mold Dictyostelium crawl towards one another. Eventually they aggregate into a slug-like creature that crawls around for a bit. Cells that find themselves in different parts of the slug differentiate into specialized types and together the community of cells (organism?) forms a base, a stalk and a fruiting body to launch spores (towards the end of this clip you can see the base and stalk on the left, the fruiting body filled with hopeful spores is just off screen to the left)..

Yeast

Fungi, plants, and animals, we are all eukaryotes. We are certainly different from one another, yet we are related closely enough that our genes are sometimes interchangeable. In a dramatic demonstration of this fact, Paul Nurse and Melanie Lee used a human gene to replace an essential gene in a single-celled fungus, a variety of yeast that is used in Africa to brew beer. [1]

Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the budding yeast, is another microscopic fungus, the predominant yeast that we have been using for brewing and baking for something like 10,000 years. Like the fission yeast used by Nurse, the budding yeast grows rapidly and we are adept at manipulating its growth and life cycle in the lab. Yeast is a strikingly good model organism for a growing array of cellular processes, including cell division.

Dividing yeast cells courtsey of the Salmon Lab, University of North Carolina

.

Yeast has proven itself so useful that hundreds of independent laboratories from around the world use it as a model organism. These scientists have developed sophisticated technologies that allow them to probe deep into the workings of cellular processes such as cell growth and division.

Cell growth and division may look simple, but consider what is being accomplished: cells grow and divide in just the right balance to maintain cell size within a limited range – too much division with not enough growth produces wee cells and vice versa. Cells must be able to assess their own size and then divide with exquisite precision. Cell division is not initiated until each strand of DNA is completely copied once and only once. Each daughter cell receives precisely one copy of each chromosome along with a share of mitochondria and other essential organelles. The more we learn about the molecular machines that control and execute these feats, the more stunning it all becomes. The mysteries are deeper with every layer that is pulled back. And the relevance to humans is unambiguous: cancer is cell division control gone awry.

Dance of the chromosomes: vertebrate cell division

As useful as yeast continues to be, there are some questions for which yeast is of no use at all. We tend to think of evolution as a process of acquiring ever more fancy ways of doing more and doing it better, but often it goes the other way. When conditions change, structures that previously served a purpose may no longer be of any use. Because it costs energy to build structures, individuals with a mutation that prevent the structures from being built can put the saved energy into other things – breeding being an eternal favorite. Such was the case in the deep caves of Mexico where light does not penetrate. After generations in complete darkness, a fish known as the Mexican cave Tetra no longer has eyes.

Like the eyeless Mexican Tetra, yeast is a bit weird in that it is a stripped down little creature. Over evolutionary time, yeast has lost some features, presumably because the cells have adapted to environmental niches where these features are of no use. Among the attributes that yeast lost are cilia, small hair-like structures that protrude from the surface of the cell.

How do we know that one lineage (e.g. yeast) lost something (cilia) as opposed to the possibility that the thing never developed in that lineage to begin with? We know because cilia appear in all major branches of the eukaryotes and in each case they are fundamentally the same, built from the same complex array of molecules assembled in the same way by the same molecular machinery. The last common ancestor of plants, animals and fungi was a single-celled organism with cilia.

.

How I Met Chlamydomonas

Chlamydomonas is a unicellular organism that has some of the attributes that recommend yeast, with the bonus that it has retained its cilia. This microscopic green alga is found worldwide living in soils, ponds and even on snow. All they need is light, water and a few minerals – they grow well in a flask of fertilized water on a windowsill. Specific cellular traits have made Chlamydomonas a valuable model for energy capture (photosynthesis of crop plants, biofuels and artificial leaves), cellular stress responses, mechanisms of evolution, and an array of human genetic diseases. Although I now use Chlamydomonas as a model organism to study the biology of cilia, that is not where my relationship with this cell began.

I first met Chlamydomonas in 1988 when I was doing my Ph.D. dissertation research in genetics and biochemistry at the University of Connecticut. I was part of a team trying to understand how the leaves of the majestic Rain Tree fold up at night (to conserve water) and unfurl in the morning (to capture sunlight).[2]

At night the cells on the inside of each tiny elbow of the leaf shrivel while those on the outside expand, causing the elbow to bend and the leaves to fold. Each morning the process reverses, the elbows straighten and the leaves unfold. We were interested in how these cellular shape changes were controlled by a circadian clock. Sapling trees kept in the dark for days at a time continue to fold and unfold their leaves in time with the changing light outside.

We were testing the hypothesis that a particular biochemical pathway was involved in coupling the cellular shape changes to the circadian clock. The work involved growing sapling trees in large light-controlled growth chambers, harvesting the tiny elbows and incubating them in small vials of radioactive fertilizer, where they would continue to bend and stretch even while detached from the plant. After the elbows had taken up and incorporated the radioactivity into their cells, we would carefully dissect the inside of the elbow away from the outside of the elbow, freezing each section of tissue on dry ice, grinding with a mortar and pedestal, and then conducting biochemical analysis of the material. It was slow, painstaking work and we were not getting clear answers.

At the time we didn’t even know whether the biochemical pathway of interest was used to regulate activity in cells in the plant lineage. I wasn’t familiar with the concept of model organisms, but as an oceanography student I had worked with single-celled algae.

I soon started growing my first Chlamydomonas cells and it was love at first sight – they are green, they are beautiful and using them for this project was a way of bringing together my long-time fascination with algae and my new interest in biochemistry.

.

Getting To Know My Organism

Eventually I got the experiments working and determined that the biochemical pathway we were looking for was present in Chlamydomonas. I was getting to know my organism. After learning how to grow it and how to manipulate it for experiments, the next step was to see if our pathway controlled any of the behaviours of this tiny alga.

I surveyed three behaviours: phototaxis, mating and deflagellation. Phototaxis is directed movement in response to light: Chlamydomonas cells swim towards dim light and away from bright light. Mating is, yes, sex. Chlamydomonas comes in two mating types, plus and minus – male and female, just like us (as it were). Flagella[3] on cells of opposite mating type stick to one another, bringing the cells together for fusion. The third behaviour, deflagellation, is a stress response wherein Chlamydomonas jettisons its flagella, to grow new ones later when the stress has passed.

Phototaxis and mating are both complex behaviours. I didn’t find any evidence that our biochemical pathway was involved in either, but then, I didn’t know the organism well enough to finesse the experiments. Thankfully, deflagellation was simple: shock the cells with a chemical treatment and the flagella would pop off. I was lucky and discovered that our biochemical pathway kicked into high gear during deflagellation.

Excited by the biochemistry, I detoured into postdoctoral research at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas where I studied the molecular pathways by which mammalian cells respond to hormones. But I pined for Chlamydomonas. Eventually I established my own lab at Emory University specifically focused on the problem of how and why Chlamydomonas cells deflagellate.

.

Intimacy

One particular memory stands out from those early years in my own lab when I was getting to know my organism more intimately. It was late in the evening and no one else was around. While waiting for an experiment, I was occupying myself by sitting at the microscope watching Chlamydomonas.

Under the microscope you can see the cell wall for which Chlamydomonas is named. “Chlamys” is Greek for “a shoulder draped cloak.” That night I happened upon a mother cell wall containing the daughters from a recent cell division. I saw the evidence of three divisions in rapid succession: eight Chlamydomonas daughter cells still encased in their mother’s cell wall. Over the next hour and a half I watched as the daughters grew flagella and started waving them about within the confined womb. Eventually, they managed to rip a hole in the wall and one by one I watched the cells emerge and swim away.

The cilia that protrude from almost all of the cells in the human body are essentially the same as those of Chlamydomonas. Some of our cells, such as those lining our respiratory tracts and the ventricles of our brains, are topped with a cluster of motile cilia that serve to move fluids – mucus and cerebral-spinal fluid, respectively. Primarily because of experiments on Chlamydomonas scientists are beginning to understand the molecular machines that generate this beautiful form of motility.

Cilia of mouse brain ependymal cells maintaining flow of cerebrospinal fluid. Movie courtesy of Karl Lechtreck, University of Georgia.

The cells that make up most of our tissues – brain, liver, kidney, muscles, skin – have only one, very small and non-motile, cilium. Until recently, scientists ignored these relatively pathetic looking little structures with no assigned function, considering them to be vestiges of our evolutionary past. A little over a decade ago, Chlamydomonas researchers seeking to understand how cilia are built made discoveries that have lead to a revolution in our thinking about ‘vestigial’ cilia.

Over the past dozen years we have learned that these tiny immotile cilia serve critical roles as cellular antennae, processing centres for the myriad signals that cells are tuned to detect. Signals from the environment and from other cells dictate differentiation into the various cell types that make up the organs of our body. Similar signals that maintain the physiological functioning of the adult. Both developmental and physiological signals are detected and integrated by cilia. Commensurate with the varied and important signals that cilia process, we are now discovering that defects in cilia cause a long list of diseases ranging from too many fingers and toes to obesity to Polycystic Kidney Disease and retinal degeneration.

.

Flies and Worms

Research in both Chlamydomonas and yeast depends upon the study of heredity, or genetics, a tool that is available because of research on another model organism, the fruit fly. Thomas Hunt Morgan followed visible traits of Drosophila melanogaster to discover that genes carried on chromosomes are the basis of heredity. [4]

As with other model organisms, Drosophila became ever more useful to scientists the better they came to know it. Experiments in Drosophila revealed master control genes in charge of establishing whether a leg or an eye would develop and fly researchers were among the first to decipher the language used by cells in a multicellular organism to establish their division of labor. Drosophila continues to be an important model organism for studies of developmental biology. Because Drosophila exhibits complex behaviours that are controlled by a nervous system and can be dissected genetically, it has also become an important model for behavioural neuroscience.

In his acceptance speech for the shared 2002 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, Sydney Brenner said, “Without doubt the fourth winner of the Nobel Prize this year is Caenohabditis elegans; it deserves all of the honor but, of course, it will not be able to share the monetary award.”[5] . Selected for the transparency of its embryo and the limited number of cells in the adult worm (fewer than 1,000) C. elegans is a premier organism for studying the how cells distinguish themselves from one another and live or die to serve the development of complex organ systems.

Crawling C. elegans courtesy of Bob Goldstein, University of North Carolina.

These are brief introductions to a few of my favorite model organisms, there are many more. Experiments with model organisms continue to help us understand the molecular interactions that underlie cell growth, division and differentiation, the development and physiology of organisms. Can life be distilled into molecular interactions whose chemical properties we can measure and ultimately predict?

.

A Feeling For The Organism

Barbara McClintock (1902-1992) was a botanist and geneticist who studied corn. McClintock discovered genetic recombination, mobile genetic elements, centromeres, telomeres and genetic regulation decades in advance of our molecular understanding of these things. She was one of the most brilliant minds of the last century. Recognized with many awards, including the 1983 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, this woman of uncontested scientific acumen had something of a spiritual relationship with her organism.

“I start with the seedling, and I don’t want to leave it. I don’t feel I really know the story if I don’t watch the plant all the way along. So I know every plant in the field. I know them intimately, and I find it a real pleasure to know them.”[6]

The mysteries of life remain so numerous and profound that researchers pushing the edges of our understanding are prone to witness strange happenings. Perplexing new observations become new discoveries – after you make sense of them. On the report of some new cellular activity it is not uncommon to hear scientists say, “I saw that too. I just didn’t know what to make of it.” Those with an intimate knowledge of their organism are better equipped to discern important changes and to make the intuitive leaps that turn perplexing observations into new knowledge.

The intuitive knowing that arises from familiarity is entwined with an awareness of kinship, of common origin. We may lose ourselves in pursuit of the specific mysteries of our creature, yet always what we are doing is revealing who we are. From small and specific questions arise big answers.

We grow fond of these quirky distant cousins who at times can be quite disagreeable (ask any cell biology graduate student). And on those rare occasions when our model organisms reveal their secrets and provide us with discoveries, the fondness feels like love.

— Lynne Quarmby

- Lee, M. G. & Nurse, P. Complementation used to clone a human homologue of the fission yeast cell cycle control gene cdc2. Nature 327, 31-35 (1987). For this and other discoveries Nurse shared the 2001 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.↵

- The Rain Tree, native from the Yucatan Pennisula to Brazil, and naturalized around the tropical world, is known by many names: Monkey Pod; Mimosa; Saman; Coco, French, or Cow Tamarind. To scientists it is Samanea saman.↵

- In Chlamydomonas the cilia are called flagella simply because way-back-when scientists did not appreciate that they were the same structure. Bacterial flagella are something entirely different.↵

- This discovery won Morgan the 1933 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine.↵

- Sydney Brenner, Robert Horvitz, and John Sulston shared the prize “for their discoveries concerning genetic regulation of organ development and programmed cell death.”↵

- From A Feeling for the Organism: The Life and Work of Barbara McClintock by Evelyn Fox Keller, 1983. (p. 198)↵

A gallerist in Saratoga Springs for over 15 years, visual artist & poet

A gallerist in Saratoga Springs for over 15 years, visual artist & poet

Patrick O’Reilly was raised in Renews, Newfoundland and Labrador, the son of a mechanic and a shop’s clerk. He just graduated from St. Thomas University, Fredericton, New Brunswick, and will begin work on an MFA at the University of Saskatchewan this coming fall. Twice he has won the Robert Clayton Casto Prize for Poetry, the judges describing his poetry as “appealingly direct and unadorned.”

Patrick O’Reilly was raised in Renews, Newfoundland and Labrador, the son of a mechanic and a shop’s clerk. He just graduated from St. Thomas University, Fredericton, New Brunswick, and will begin work on an MFA at the University of Saskatchewan this coming fall. Twice he has won the Robert Clayton Casto Prize for Poetry, the judges describing his poetry as “appealingly direct and unadorned.”

Mark Sampson has published two novels – Off Book (Norwood Publishing, 2007) and Sad Peninsula (Dundurn Press, 2014) – and a short story collection, called The Secrets Men Keep (Now or Never Publishing, 2015). He also has a book of poetry, Weathervane, forthcoming from Palimpsest Press in 2016. His stories, poems, essays and book reviews have appeared widely in journals in Canada and the United States. Mark holds a journalism degree from the University of King’s College in Halifax and a master’s degree in English from the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg. Originally from Prince Edward Island, he now lives and writes in Toronto.

Mark Sampson has published two novels – Off Book (Norwood Publishing, 2007) and Sad Peninsula (Dundurn Press, 2014) – and a short story collection, called The Secrets Men Keep (Now or Never Publishing, 2015). He also has a book of poetry, Weathervane, forthcoming from Palimpsest Press in 2016. His stories, poems, essays and book reviews have appeared widely in journals in Canada and the United States. Mark holds a journalism degree from the University of King’s College in Halifax and a master’s degree in English from the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg. Originally from Prince Edward Island, he now lives and writes in Toronto.